duga

Diabate, Massa Makan. 1970. Janjon, et autres chants populaires du Mali. Paris: Présence Africaine.

(Duga)

pp. 69–78

A l'origine, Duga n'était le faasa de personne, il était consacré aux rescapés de la mort, ceux qui avaient été laissés pour morts sur le champ de bataille en proie aux vautours.

Ensuite en jouant son nom, Koré Duga Koro (1) l'a accaparé ; après, ce fut le tour de Da Monson qui fit du vautour son emblème.

Aujourd'hui, au même titre que le Janjon, la Tara et le N'nyaro, le Duga est un hommage à l'action.

(1) Duga : tant en malinke qu'en bambara signifie le vautour.

Ce soir-là, Koré Duga Koro avait bu plus que de coutume. Couché dans son hamac, il somnolait en rêvant à de nouvelles conquêtes. Et l'exaltation des nkoni, et le chant des femmes donnèrent à son ivresse une agressivité narquoise.

Il se leva, pouffant de rire et s'étira longuement.— Va, sur-le-champ à Ségou, dit-il à un esclave, informer Da Monzon que le coton est bien venu à Korè. Nos femmes en ont tiré des ballots de fil. Sa réputation de tisserand m'est connue. Qu'il vienne donc se mettre à mon service moyennant un bon prix.

Il se recoucha, toujours pouffant de rire, prit sa gourde de vin, la vida goulûment et ordonna aux griots de jouer plus fort. Et les femmes émerveillées, chantèrent la gloire de Duga à s'éclater la poitrine.

« Seigneur des Savanes,

C'est à toi que je m'adresse, Karadige,

Toi qui marches sur quinconque te dit non... »

Da Monzon reçut l'injure sans affecter le moindre signe de colère. Il eut même la force de dessiner un sourire bonhomme sur ses lèvres.

— Tigné Tigiba né Tigiba Dante, dit-il, réponds à ce messager selon ton bon plaisir.

— Envoyé de Koré Duga Koro, dit le vieux conseiller, tu diras à ton maître que le roi de Ségou demande un délai de trois mois pour apprendre le métier.

Quand le messager sortit de la salle du trône, Da Monzon entra dans un colère démente.

— Trois mois pour détruire Koro ! y penses-tu, Tigné Tigiba Dante ? Un jour aurait suffi...

— Les jours de parade, je me plais à te présenter plus puissant que tu ne l'es ; mais lorseque nous sommes seuls...

— C'est bien ainsi que je t'aime, alors parle !

— Koré Duga Koro te surpasse en nombre, et la ruse est le seul remède à la faiblesse. Envoie un moud d'or à sa favorite. Promets-lui les pierres les plus précieuses. Promets-lui le trône de Ségou à la seule condition qu'elle t'aide contre son mari. Après la victoire... la victoire ne donne-t-elle pas le droit de vie et de mort sur les habitants du pays conquis ?

— Non... Parjure et assassin à la fois ! non, Tigné Tigiba Dante !

— Elle aura trahi son mari. Qu'elle meure c'est justice. Et comment pourrais-tu à l'avenir avoir confiance en elle ? Ell aura trahi son mari ; les portes de l'enfer s'ouvriraient toutes grandes pour la recevoir. Et Dieu bénirait qui l'y enverrait...

« Duga de prestance !

Duga de magnificence !

C'est à toi que je m'adresse, Karadige.

Oiseau à quatre ailes !

Tout en plannant, il picore.

Et en agrippant le sol de ses serres,

Il creuserait un puits dans le roc. »

Et Duga bercé par le chant des femmes s'endormait grisé de vin, dans une confiance sereine. Quand il se rappelait l'injure faite à Da Monzon, il en riait, se frappant sur le ventre.

— Le roi de Ségou est bien lent à relever un défi. A-t-il compris que je lui déclarais la guerre ?

« O Duga buveur d'un vin réchauffant

Tu ne restes jamais

Sur ta soif de vengeance. »

Il se levait en titubant et convoquait tous ses chefs de guerre.

— Demain nous irons à Ségou. Da Monzon est bien lent à venir. Nous boirons demain du Koro Koro Kunba à Ségou.

« O Karadige,

Je te parle des hommes,

Des hommes qui par leur faits

S'inscrivaient dans une action louable.

Tu sais, Duga

L'homme qui s'est accompli

S'il est loué par les uns,

Est vilipendé par les autres

Karadige !

Si petit par la taille,

Si grand par ses exploits ! »

Et Koré Duga Koro s'endormait les poings fermés sur ces paroles rassurantes.

Au réveil après avoir cuvé son vin, il s'étonnait de voir son armée rassemblée prête à entrer en campagne. Il revenait sur ses ordres et les femmes dès le matin enivraient Duga de leur chant :

« O Seigneur des savanes !

Cette nuit encore

Le mauvais parent

A sacrifié contre ta puissance

Une noix de Kola blanche.

Mais rassure-toi, Karadige,

Est-ce là son premier méfait ? »

Un matin, à peine d'était-il réveillé, qu'un messager vint dire à Duga que Da Monzon approchait.

— Sait-il enfin tisser le coton ?

— Pendant trois mois, il s'est attelé à l'ouvrage. Mais il préfère la guerre, son premier métier.

— La guerre, son premier métier ? nargua Duga.

« Duga va vite

Duga revient vite

Karadige s'est envolé

Et ce soir-là

Mari, roi de Baguineda

A mordu la poussière. »

Vêtu d'un boubou écarlate, Duga allait et venait. Il donnait un conseil à un de ses chefs, prenait l'avis d'un autre, et les femmes chantaient les victoires passées.

« Il advint qu'un jour

Duga se fâcha,

Son armée aussi.

Il prit son arce et ses flèches

Et s'envola jusqu'à Jakuruna.

Là, il écrasa Toto ;

Il l'a incarcéré

Et l'a fait décapiter.

Son corps s'est trémoussé

Comme le boeuf qu'on sacrifiait

Au Mande avant les grandes batailles. »

Le choc fut rude pour Koré Duga Koro. Après trois jours de combat, ses guerriers étaient désarmés, car quelqu'un avait inondé la poudrière.

— Irons-nous à Ségou ? demandaient tous les chefs. Da Monzon entre en triomphateur. Irons-nous à Ségou ? Sans répondre, Duga se dirigea vers l'est et s'arrêta devant une mare. — La honte me pourchasse. J'entends ses pas soulevant une gloire de poussière. Je vois le sourire épanoui de Da Monzon. A Ségou, la foule me conspue. Ah le crachat de tonjon sur mon visage... Crocodile, notre pacte, t'en souviens-tu ? — Je prends un bras, je le tiens ; je donne une parole, je la tiens. Entre dans mon ventre, dit le crocodile en ouvrant toute grande sa gueule. Personne d'autre que toi-même ne viendra t'y chercher. — Moi-même me livrer à Da Monzon ?... — Oui, avoir confiance c'est quelquefois se trahir. — Ma femme ! ma favorite... s'écria Duga. On chercha en vain Duga parmi les morts, parmi les blessés, parmi les captifs. — La femme connaît le secret de l'homme, et l'homme celui de la femme, opina Tigné Tigiba Dante. On fit venir la favorite de Koré Duga Koro. — Où est ton mari ? — Dans le ventre du crocodile solitaire qui vit dans la mare à l'est de Koré. Les tonjon retirèment l'eau du marigot et s'emparèrent du crocodile enfoui sous la vase. Ils l'éventrèrent, Duga sortit aveuglé par la lumière du soleil. — Je suis venu tisser ton coton, dit Da Monzon triomphant. Où sont les ballots de fil ? Koré Duga Koro ne répondit pas. — Karadige n'est volubile qu'en état d'ivresse. Qu'on lui apporte du Koro Koro Kunba, et du vrai. Le Koro Koro Kunba de Ségou.— J'aime le vin, mais agrémenté de musique. — Alors griots de Koré, chantez pour votre maître.

« O Karadige,

Buveur d'un vin réchauffant.

Tu ne restes jamais

Sur ta soif de vengeance.

C'est à toi que je m'adresse,

Karadige !

Oiseau à quatre ailes,

Tout en plannant il picore.

Et s'il agrippait le sol de ses serres

Il creuserait un puits dans le roc. »

A entendre cette chanson, lentement Duga se couvrit de plumes et s'envola haut, très haut au-delà des nuages.

— Non, se dit-il, je ne peux abandonner mes griots á Da Monzon. Il s'abaissa, plana longtemps sur Koré et la pierre sur laquelle il s'assit s'ouvrit sous le poids de son corps. — Roi de Ségou, ta victoire, tu la dois à la trahison de ma femme. Une inquiétude assombrit son visage. — Que vas-tu fair de moi, Da Monzon ? — Tu viendras à Ségou avec tes griots. — Karadige n'ira pas à Ségou, Da Monzon. Et Karadige ordonne à ses griots de se donner la mort. De nouveau, il se transforma en vautour, et s'envola haut, très haut au-delà des nouages. Lentement, il s'abaissa, plana longtemps sur Koré et comme la première pierre ne pouvait plus résister au poids de son corps, il s'assit sur une autre. — Partir, mais où partir si nulle part je ne serais chez moi ? Il se leva, prit le fusil d'un tonjon et le chargea. Ensuite il se défit de tous ses talismans... Au bruit que fit la détonation, sa femme accourut. — Roi de Ségou... — Tigné Tigiba Dante, qu'on donne à cette femme tout le butin de Koré. En outre, je me désiste de mon trône en sa faveur. Mais luis avais-je promis la vie sauve, Tigné Tigiba Dante ? — Je ne m'en souviens pas. L'armée regagna Ségou en chantant une nouvelle chanson.« Ségou !

On peut y précéder un autre

Ségou ?

Tout le monde devra

Un jour prochain

Venir à Ségou.

Le prince possesseur

D'un fusil à double canon

Viendra à Ségou.

Le prince propiétaire

De grands parcs et de chevaux

Viendra à Ségou.

A Ségou il est

Un bien vieux vin.

N'en boit pas qui veut. »

Oui, Da Monzon est irrésistible.

Ministère de l'information du Mali. 1971. Première anthologie de la musique malienne: 5. Cordes anciennes. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2505.

(Duga)

It is not really known whether Duga is a Malinké or a Bambara song, so much these two ethnic groups of the steppes and savannas have intermingled in the course of history as regards their languages and customs. Anxious to provide a certain diversity, we here present the Bambara version. Duga celebrates the great wounded soldier who returns to life. It signifies vulture, that rare bird which frequents the far-off forests and is the object of a regular worship:

I address to you, Duga!

You, who have four wings,

You peck your food as you glide.

And when landing on the ground

You always dig a well

Similar to a natural well.

Ministère de l'information du Mali. 1971. Première anthologie de la musique malienne: 6. Fanta Damba: La tradition épique. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2506.

(Duga)

One of the most famous songs in the Mandingo country. It celebrates the great wounded soldier who returns to life.

Bird, Charles S. 1972. "Heroic Songs of the Mande Hunters." In African Folklore, ed. Richard Dorson, 275-93, 441-77. Bloomington: Indiana University.

(Duga)

p. 280

Some of the ritual songs, such as the Janjon, can be danced only by men who have made a major kill, i.e., a lion, an elephant, a bush buffalo, or a man. The Duga is, in some areas, a ritual song for warriors as opposed to hunters and can be daned only by a recognized hero, one who has narrowly escaped death in battle or has killed a man in battle. It is through songs such as these that a sort of hierarchy of excellence is established among the hunters. At the end of the typical ceremony, the hunters gather around and listen to a heroic song sung about great hunters and warriors of the past. These heroic pieces may be of one to two hours' duration and be told in the course of one evening, or, in the case of a ceremony lasting several days, the performance may continue over several evenings, and the total recitation time may run upward of ten hours.

p. 291

It can be claimed that many of the songs incorporated into the epics have their origin as hunters' songs. This is particularly evident in the case of the Janjon and the Duga, both of which are ceremonial dances of high order in the hunters' and warriors' societies.

pp. 468-77

"The Vulture" ("Duga" in Bambara) is the oldest and most widespread song known in West Africa, recorded in early Arabic texts. It is a praise song for warriors and hunters celebrating heroism. This story begins with the song being sung for the King of Koré, but since Da Monson defeats him, the song becomes a tribute to the victor and was incorporated in the epic cycle for Da Monson. . . . It was customarily sung for the warriors who killed a lion, an elephant, or another warrior.

It was sung by Bakoroba Kone, an elderly bard, in Segou, April 1968, accompanied by two female singers, Penta Donte and Hawa Kone, who sang the songs inserted at intervals in the epic recitation (indicated by indentation).

Mawula! Mawula! Karadige,

no man speaks against the vulture

when the eagle is not on wing.

The beer drinkers behind the river

and bitterness never meet.

Ah! Karadige,

the brave is a man of the moment

but where are the braves of yesteryear?

No matter how good a man may be,

words will be said behind his back.

Ah! Karadige, I call to you,

little man, great man.

In the name of Allah,

whose prophet is Muhammed,

the matter turned badly for the cursed child.

It is the truth she sings.

This was sung for the Old Vulture of Koré,

the king seated in Koré.

This was sung for him by his bards.

No matter how good a man may be,

words will be said behind his back.

One time having drunk too much

and lying about in his palace,

he told one of his slaves

to tell Da Monson of Segou

that Da should know there was thread

to weave in Koré.

"I've yet to find a weaver for it.

Tell him to come weave my thread.

Go quickly, come back quickly!"

Ah! Karadige.

The day that Baguinda Mari fell,

the eagle was flying;

and that day of battle in Nyamina . . .

No matter how good a man may be,

words will be said behind his back.

The servant came and delivered the message to Da.

Da spoke to his bard:

"Dante, great master of truth," he said,

"Didn't you hear the words of tbe messenger?

He said we should go.

He said he had some thread.

He said that Segou should come weave his thread.

He said he knows not of Segou,

but our weaving."

And he said, "Master of truth,

send him on his way."

He spoke to tbe messenger, saying:

"When you arrive, tell him

that Segou will come and weave his thread

so that it will be beautiful.

O Vulture of majestic flight!

Vulture of beautiful flight!

One bird, four wings.

O bird who floats in the skies

and yet can scratch the ground.

When the bird lands,

he gouges a well,

a well of God,

like a well in tbe Mande mountains.

Da Monson spoke: "Master of Truth,"

he said, "what is your thought on these words?"

"Because of these words," he replied,

"I think of one thing,

a measure of gold.

If you take one and

give it to a man

to give to the Old Vulture's first wife,

so that she will help us in this matter,

then, the way to the Vulture of Koré"

she will tell it to us."

O Eagle, only treachery can destroy familial love.

Descendance from the woman,

descendance from the woman has ended.

But descendance from the woman is better than sterility,

and sterility is better than an evil child.

They took out a measure of gold

and placed it in the hand of a man

who gave it to the first wife of Vulture,

telling her that this was the cost of kola,

saying that Segou spoke thus,

that this was her gift,

and as such, the rest remains in Segou.

She must, he said, apply herself

and tell us the way to capture the Old Vulture.

That is the work you must do for us.son

Oh! In the name of Allah!

The bird suffered much.

He slung the quiver on his shoulder.

He grabbed the bow in hand

to go seize Jakuruna Toto,

right up to Jakuruna;

and he cut off his great head

at the wide opening of his throat;

and his head rolled on the ground

hke a sacrificial bull of a Mande brave;

and he, he got off with great effort

to seize Samanyana Basi,

right up to Samanyana.

The woman sent a man

to tell them that her husband

was a man who already knew his destiny.

He spoke with a crocodile.

She said that

if they did not move to the west of the village,

they would spend a year without defeating the Old Vulture.

As soon as the messenger came to say this to Da Monson,

and as soon as they understood these words,

they took the camp baggage,

and moved between the village

and the setting sun.

The first wife ran out to them

throwing herself On her knees before them:

"Dante, Master of Truth, tell the king I have come."

"Did you receive the message," he replied.

"Yes, I received the message."

"Wonderful," he answered. "This is but a gift for you.

The rest awaits you in Segou,

so that you will help us in our task."

In the name of God,

whose prophet is Muhammed,

a man is not God.

Koliko Duga Sirima became angry

and angrier and angrier.

He jammed his quiver On his head,

seized his bow in one hand,

and went to capture Sobe Masa

alive!

Come quiet, Bajubanen.

Leave loud!

When they finished talking,

she returned to the village

and assembled her servants.

They carried water and

brought it to the powder room,

where they wet all the powder.

When the powder was all wet down,

she sent a man to tell Da Monson:

"Surround the village.

I have done my work!"

The battle raged for three days.

Segou could not break through.

As soon as the original rifle charges were exhausted,

those who went to get fresh powder

found the powder wet.

They went to Vulture saying: "King!"

"Yes."

"And the powder, wasn't it made ready?"

"It was made ready," he replied.

"Well, it has all become water!"

"Then," he asked, "who will go to Segou?

Is it we who will be captured by Segou?

Now, that's an incredible thing!"

He left to go look,

and found all the powder wet.

Three days passed.

They were finally able to crack through to the

Old Vulture's wells.

They destroyed everything without value

and carried off the rest.

The Old Vulture ran off to the men's house,

where the great crocodile awaited him.

It swallowed him and went to lie in the pond.

Da Monson's warriors looked everywhere for him,

but they didn't see him.

They began an investigation.

"A man's secret is always held by his woman.

A man's secret is always held by his woman.

Ask the woman!"

They called the woman and came with her.

The woman said her words were true.

"The great pond to the east,

That is where he and the crocodile speak.

That's who is his total master.

If, therefore, you empty the pond completely,

and you find the crocodile,

You will see him."

They all worked together,

completely emptying the pond.

The crocodile tried to flee,

but they grabbed it and cut open its stomach,

pulling the Old Vulture from inside.

"Old Vulture of Koré!"

"Yes?"

"You said Segou should come weave your thread,

and thus, we have come.

Give us some thread to weave for you."

They brought the Old Vulture of Koré out,

and sat him down in the village square.

They called the Vulture's bards.

The bards having been called, Da Monson said:

"That which you have sung for the Old Vulture of Koré,

You will sing before us now for all to hear,

because today you will go to Segou."

When this was said,

the Old Vulture, seated among his bards,

grew angrier and angrier.

In his great anger, he transformed himself

and Hew off into the sky.

He circled about in the heavens

and then Hoated back down.

"Da," he said, "you alone are not able to defeat me.

It's my wife who betrayed me.

If she hadn't betrayed me,

you never would have defeated me."

He sat back down among his bards.

Again he grew angry

and again he transformed himself

and again he flew off into the sky

until he could calm himself.

He retmned once more and said:

"Da, you still can't defeat me,

but I will not leave my bards in your hands.

Do with me what you will."

"What would please us," Da replied,

"is to bring you back to Segou."

And the Old Vulture responded: "That cannot be me,

Segou will never lay its eyes on me.

You'd better put that idea aside."

"Well, your bards," Da suggested,

"we will take them to Segou."

But the bards were quick to reply,

"Segou will never lay eyes on us.

We have drunk honey wine together.

Should it be a question of a more bitter drink,

we'll drink that together, too."

On saying this, the bards all killed themselves.

The Old Vulture turned to Da

and said that Da could never kill him,

that Da could never capture him,

but if Da would permit it,

he would kill himself.

If permission were not granted,

no one would be able to defeat him.

The Vulture took all the amulets from his body,

then grabbed a rifle and shot himself.

This done, the woman ran up, saying:

"King, as you have requested, so have I done."

He answered her, saying, "Thank you for your help.

You have greatly pleased us.

That which you have done for us,

its reward is not here with us.

That which you were given,

do you still have it here?"

"Yes, it is here," she replied.

"Then bring it here to us.

Didn't we tell you.

the remainder awaits you in Segou?

It is being kept there for you."

The woman returned with the gold.

"Thank you," Da said, "you made no mistake.

But, Dante, Master of Truth, tell this woman

that we are right to fear her.

We cannot take her to Segou.

If we were to take her to Segou,

once my power was established,

if anyone were to try to crush me,

she would help him find my secrets.

I cannot take her back.

Add her to her man over there."

They bashed in her head

and threw her body by her husband's.

And Da, calling out to his drummers,

his trumpeters, and his bards, said,

"Well, let's be off to Segou

and those things of which you will sing;

if you are to sing them in Segou,

you'd better prepare them well!"

Ah! The offering of white kola by evil kin

Mawula!

None of that is new to the Vulture.

Who would speak against the Vulture?

Samanyana Basi spoke against him,

and his head was cut off

at the opening of his great throat

Ah, Bajubanen!

You might say a sacrificial bull of a Mande brave.

It is said that the poor man,

if he should speak of the affairs of kings,

will be given away as a gift by the king.

They returned to Segou;

three hundred battalions in Segou.

They gathered together

and sat in the square.

There was much beer

and honey wine.

Thus they celebrated right down to the fieriest brew.

Oh! Segou! One can succeed in Segou.

Oh! Segou! There is no one who doesn't go to Segou.

E! Even if a double-barreled king,

even if he were a king with a house of bards.

You are a great warrior, Karadige,

but Da was the greatest of warriors.

(Douga)

p. 219

Douga, chant guerrier par excellence, est la musique de tout guerrier qui s'illustre dans une bataille.

Bird, Charles S., and Martha B. Kendall. 1980. "The Mande Hero: Text and Context." In Explorations in African Systems of Thought, ed. Ivan Karp and Charles Bird, 13-21. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Reprinted Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987.

(Duga)

p. 21

The Duga, "Vulture," tells the story of two enemy heroes who have become kings: Da Monson, King of the Segou Empire, and Duga Koro, great warrior and hunter, King of Koré.10 At the beginning of the story the Duga is sung only in praise of Duga Koro, who, sure of his power and spoiling for a battle, insults his enemy, Da Monson. Da Monson marshals his forces and besieges Koré, but cannot breach the walls even after many efforts. Duga, Koro's senior wife who is bribed into betraying him, reveals the secret of his magic to Da Monson, who then successfully attacks and seizes his fortress. Duga Koro commits suicide before he can be captured, but Da Monson's warriors sack the town for booty and slaves, and Da Monson claims the Duga song for himself.

p. 25

10. The version of the Duga to which we refer was performed by Ba Kone in Segou, 1968, The reader is invited to consult Monteil (1924), Tauxier (1942), and Bazin (1971) for details relating to the reign of Da Monson and the Segou Empire in general.

Knight, Roderic. 1982a. "Manding/Fula Relations as Reflected in the Manding Song Repertoire." African Music 6 (2): 37-47.

(Duga)

p. 39

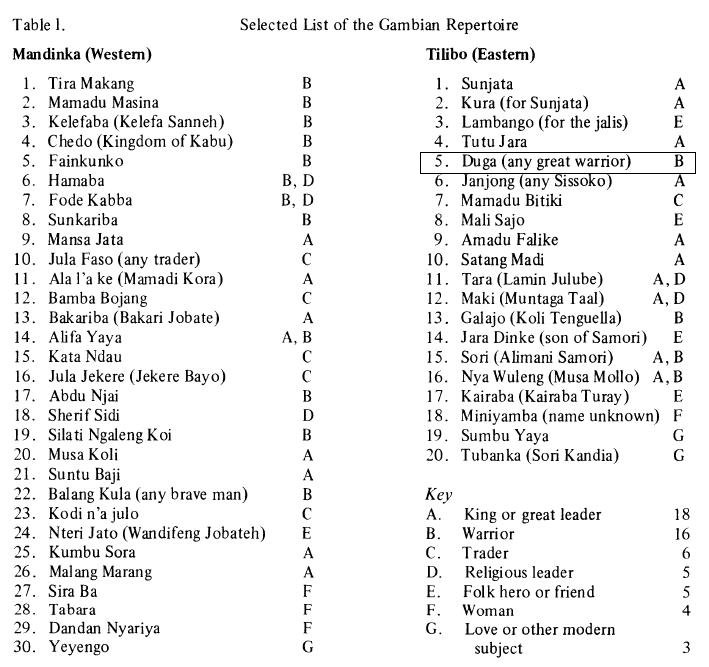

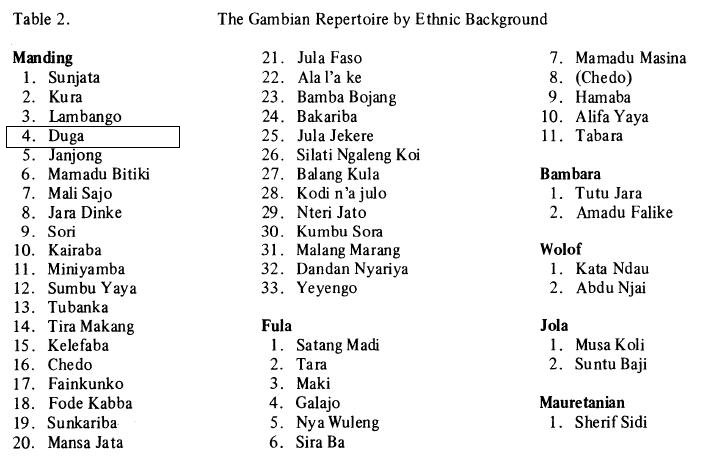

Table One . . . includes the best known, most often heard, or otherwise significant songs in the [Gambian] repertoire. In each column the top few songs are the oldest, and the bottom few are the youngest. The majority in each case fall somewhere in between (often in the nineteenth century), but no chronological ordering beyond this is intended, since it is often not possible to date a song exactly. Most of the songs bear the name of their owner as the title. Where they do not, his name is shown in parentheses next to the title. The letter code at the right represents the person's "claim to fame" or calling in life, as shown in the bottom of the list.

p. 40

Table Two shows the same fifty songs again, grouped this time by the ethnic background of the people commemorated.

Coolen, Michael T. 1983. "The Wolof Xalam Tradition of the Senegambia." Ethnomusicology 27 (3): 477-498.

(Duga)

p. 490-1

Example 4 illustrates . . . bi-partite fodets with 16-beat patterns. . . . Duga uses a duple subdivision.

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Duga)

pp. 146–59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Duga |

| Translation: | Vulture |

| Dedication: | Any great warrior |

| Notes: | vulture is a symbol of bravery |

| Calling in Life: | Warrior |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | E (13th & 14th c.) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

Knight, Roderic. 1984. "The Style of Mandinka Music: A Study in Extracting Theory from Practice." In Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, vol. 5, Studies in African Music, ed. J. H. Kwabena Nketia and Jacqueline Cogdell Djedje, 3–66. Los Angeles: Program in Ethnomusicology, Department of Music, University of California.

(Duga)

p. 8

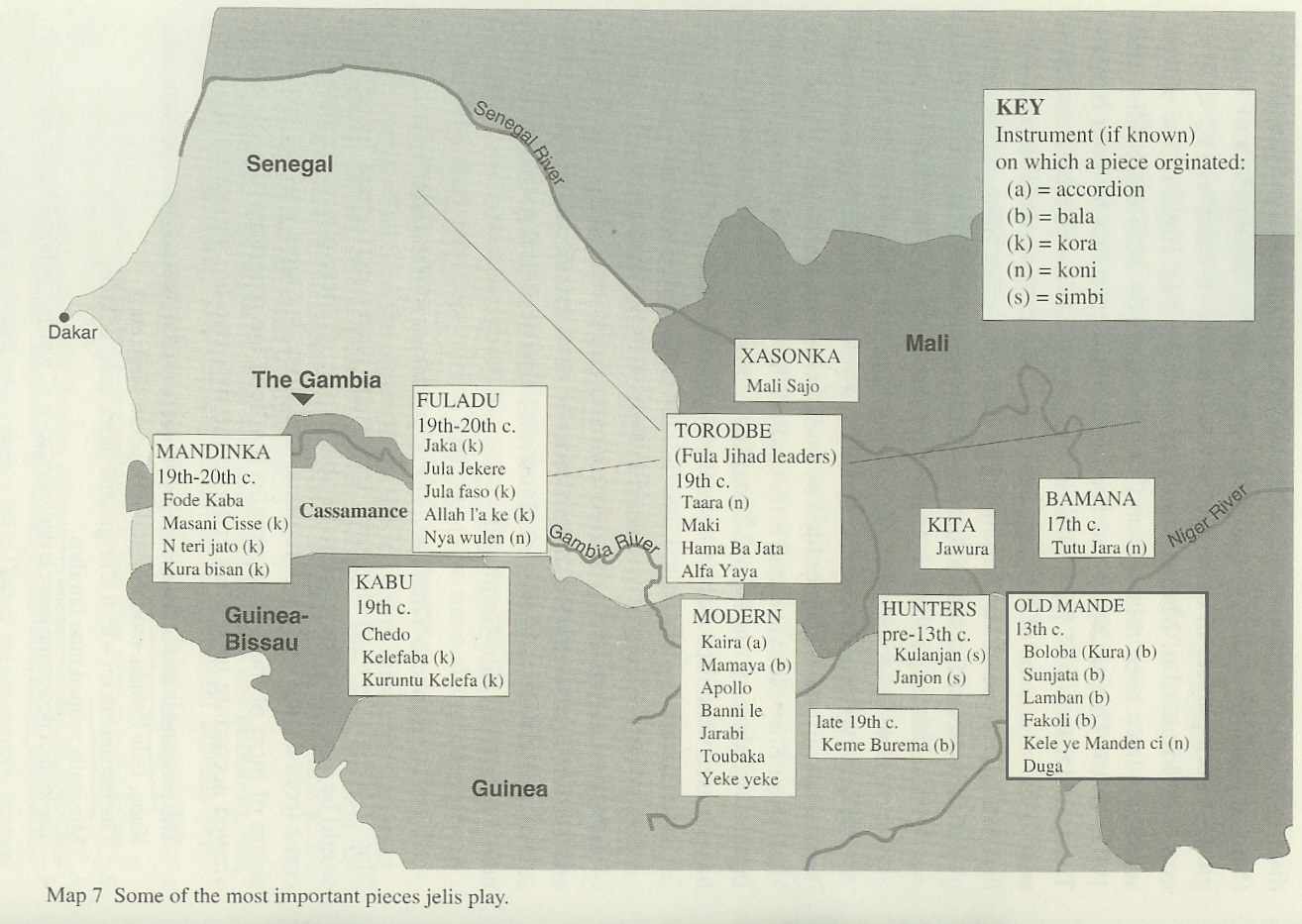

Another major theme in the donkolo texts is bravery, usually in the form of prowess in battle. The oldest song on this subject is "Duga", referring to the vulture, the bird who symbolizes bravery among the Manding. (The imagery here is drawn from the end of a battle, when the soaring vultures clearly dominate the field.) This "solemn Vulture's Tune" is mentioned in the story of Sunjata. It was formerly played only for a dance to be performed by the bravest warriors (Keita 1959:21; Niane 1965:39). Today its perfomance is not so rare or so elegant; it is performed commonly as part of the Tilibo repertoire.

p. 16

The secondary Hardino mode places the tonal center on pitch six. "Duga" (the Vulture's tune) and "Miniyamba" (Great Python) use this secondary mode.

Sacko, Ousmane. 1987. La nuit des griots. Recorded 1983. Ocora/Harmonia Mundi, HM CD83.

(Duga)

Duga, the "vulture" is considered one of the most serious songs of the Manding repertoire—not be [sic] performed onnly [sic] by musicians of stature, and delicated [sic] only to the exceptionally brave. Not many musicians claim to know the origins of Duga, but according to some, it was first performed at the time of Sunjata in the 13th century after he conquered the army of his opponent, Susu Sumanguru. So many people lay dead on the battlefield that the sky was thick with vultures, and this song is said to commemorate that awesome occasion. The name Duga in this context is symbolic of a brave warrior.

"No one can oppose vulture. [sic] Everyone was created differently, so don't blame someone for being what he cannot. No one can oppose Mori Tounkara. The white man is powerful; he doesn't play at things. The doundoung cannot make the sound of the bala, nor the bala the sound of the doundoung. King of Mali: the power lies solely in your hands."

Durán, Lucy. 1995. "Birds of Wasulu: Freedom of Expression and Expressions of Freedom in the Popular Music of Southern Mali." British Journal of Ethnomusicology 4: 101-34

(Duga)

p. 109

Duga means "vulture", a symbol of bravery and wisdom in Mande, as in the proverb "the eldest/wisest bird is the vulture" (kono korolin ye duga ye) (Sangare interview 1995). In Mande culture generally, mastery is associated with the wisdom acquired through age and experience. Thus great kono singers are termed kono koroba ("old bird") and sometimes simply duga ("vulture")(Sangare ibid).19

p. 112

Two of the oldest and most important songs in the jeli's repertoire commemorate birds: Koulandjan (marabou stork), is a song in praise of hunters, and Duga (the vulture) is about bravery in battle.25

25 Bird (1972b:4 68) describes this song as "the oldest and most widespread song known in West Africa, recorded in early Arabic texts."

Kaba, Mamadi. 1995. Anthologie de chants mandingues (Côte d'Ivoire, Guinée, Mali). Paris: Harmattan.

(Douga [Le Vautour1])

p. 22

Oh, vautour !

Oh, vautour !

Toute personne qui a désobéi

Aux ordres du vautour

L'a regretté toute sa vie

Car chacun connaît la force du vautour

Et la force ignore la résignation !

1Le vautour était l'oiseau sacré du Manding. Tout comme Koulandian, on lui dédiait des sacrifices et ses décisions étaient péremptoires et exécutoires.

Ce morceau est un chant rituel connu au Mali et en Guinée. Il met en exergue la puissance du vautour et de la société secrète dont il était le symbole. Il est chanté par les femmes mais surtout par les hommes aux voix de basse baryton.

Kouyaté, Sory Kandia. 1999. L'épopée du Mandingue. Mélodie, 38205-2. Re-issue of 1973, SLP 36, SLP 37 and "Toutou diarra" from SLP 38.

(Douga)

Très vieil hymne au courage, à la bravoure et à la victoire—Aux veillées d'armes autrefois, on ne jouait le Douga que pour les guerriers qui avaient accompli des actions d'éclat.

Arnoldi, Mary Jo. 2000. "Wild Animals and Heroic Men: Visual and Verbal Arts in the 'Sogo bò' Masquerades of Mali." Research in African Literatures: Poetics of African Art 31 (4): 63-75.

(Duga)

p. 69

The song for Duga, the Vulture masquerade, makes the link to hunting and to the hunter as hero explicit. Duga, the vulture, itself is a praise name for the master hunter. A well-known proverb that expresses these sentiments states:

Duga-mansa be jigi fen kan

fen te jigi duga-mansa-kòrò kan

King vulture may set upon anything but nothing sets upon old King Vulture (Cashion 1:245)

In the youth theater the song for the Duga masquerade builds upon this proverb to set the interpretive frame for the masquerade character:

Lead Singer:

Duga, mansa kòrò k'i be taa min

a ko n'be taa n'yaala

n'be taa n'yaala ka hèrè nyini

E be jigin fen kan fen te jigin e koni kan

Vulture, old king where are you going

He says I am wandering

I am wandering in search of good fortune

You find only good fortune.

You land on something, but nothing lands on you.

The opening line includes the praise name Old King Vulture and the final line of the lead verse incorporates the hunter's proverb. The reference in the second line to yaala, wandering, is an allusion to the dalimasigi, the hunter's adventure.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Duga)

p. 83

Ritual songs, such as Janjon and Duga, are related to the hunt and are restricted to those who have earned a reputation. The significance of ritual songs is still maintained in Mande society and widely respected.

p. 101

The griot played Duga, "the great chant which is sung only for celebrated men" (39), and Camara's father danced it.

p. 143

According to my teacher Bala Dounbouya (1989-per), the piece that Bala Faseke Kouyate played for Sumanguru was called Boloba. Wa Kamissoko was also of this opinion. Djibril Tamsir Niane (1965:39) wrote that Bala Faseke played Duga, another of the oldest pieces in the repertory.

p. 148

p. 150

The parent-child relationship of some pieces is common knowledge and is readily talked about as such among many musicians: Saxo (Sacko) Dugu comes from Duga; Jula Jekere from Janjon; and Jaka from Hama Ba Jata.

p. 151

Duga is said to be of hunter origin but I do not know of it being played on the simbi or donso ngoni.

p. 155

Duga (Vulture) is one of the oldest pieces in the Mande repertory, but it is not played on the simbi. Its basis in a minor mode indicates possible vocal or koni origins. It was originally played for warriors who had narrowly escaped death but has since been associated first with Duga Koro, king of Koré, and then with the Segu king Da Monson Jara who defeated him (Bird 1972:280, 468; Bird and Kendall 1980:21; M. Diabate 1970:69).90 The piece Sacko Dugu is musically derived from Duga.

90. Wa Kamissoko adds that jelis sing Duga on the occasion of an execution when the body is thrown to the vultures. For a discussion of the significance of Duga in modern Mande literature, see Manthia Diawara (1992:164–66).

p. 161

99. Knight cites many examples of shifted tonal centers on the kora, which he correlates with various Western modes, including Sidiki Diabate's version of Duga (Ministry of Information of Mali 1971-disc) Sacko Dugu (Sidiki Diabate 1987-disc), both with tonics on the 6th degree of Hardino; and Toumani Diabate's (1988b-disc) version of Jarabi, with a tonic on the 6th degree of Sauta.

p. 248

The earliest written source specifically indicating that Mande music was being played on the guitar may be Fodeba Keita's (1948) Chansons du Dioliba, a twenty-to twenty-five-minute play consisting of one actor rendering Keita's poetry accompanied by a guitarist. . . . In a collection of works published in 1950 as Poèmes africainees, Keita continued this idea, naming pieces from a wide variety of regions and historical eras, including Duga, one of the oldest pieces played by jelis . . .

pp. 398–401 (Appendix C: Recordings of Traditional and Modern Pieces in Mande Repertories)

Unidentified Instrumental Origin: Duga/Saxo Dugu

Unidentified (Guinea Compilations 1962a)

Keletigui et Ses Tambourinis (1976b)

Fanta Damba (1971)

Sidiki Diabate and Djelimady Sissoko ([Ministry of Information of Mali 1971, vol. 5] Musiques du Mali 1995b)

Sory Kandia Kouyate ([1973] 1990)

Orchestre National "A" du Ma1i (1970)

Orchestre Régional de Kayes (1970)

Bah-Sadio

Balla et Ses Balladins (1967)

Quintette Guinéenne (Guinea Compilations 1976)

Tata Bambo Kouyate (Ainanah Bah, 1985; Diadie Diawara, 1988)

Maa Hawa Kouyate (n.d.b.)

Sunjul Cissoko (1992)

Moussa Keita (Ntani gnini, 1937)

Ami Koita (N'-Darila, 1995)

Moriba Koita (1997)

Mama Sissoko (1997)

Colleyn, Jean-Paul, and Laurie Ann Farrell. 2001. "Bamana: The Art of Existence in Mali." African Arts 34 (4): 16-31+94.

(Duga)

p. 22

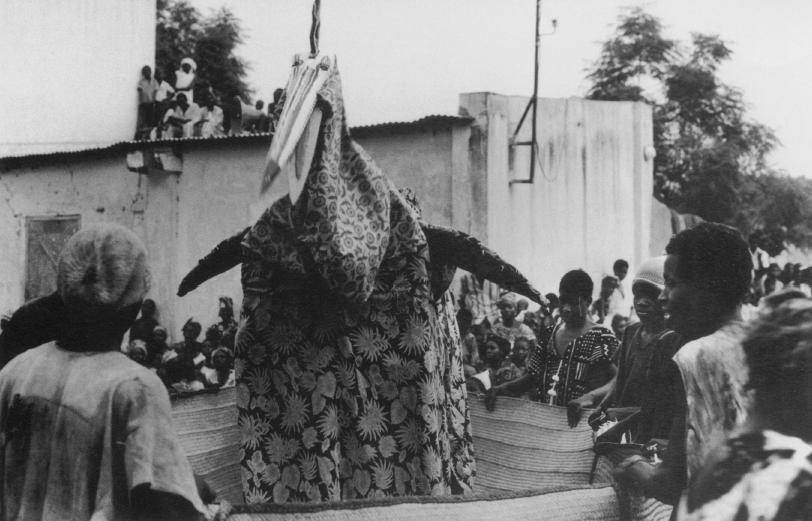

10. Duga, the Vulture in performance Kirango, 1980. Photo: Catherine De Clippe. The character of the Vulture makes an explicit link to hunting and to the hunter as hero. The name Duga is itself a praise name for a master hunter. The song for Duga reads:

Vulture Old King, where are you going

He says I am wandering

I am wandering in search of good fortune

You find only good fortune

You land on something, but nothing lands on you.

The song's opening line includes the praise name Old King, and its final line incorporates a hunter's proverb that speaks of the vulture's invincibility (Arnoldi 2001:80).

Camara, Alkhaly. 2004. Xylophone Masters: Guinea; Alkhaly Camara, Vol. 1. Marimbalafon, MBCD001.

(Douga)

"Vultures." Song in honor of prominent Warriors.

Durán, Lucy. 2007. "Ngaraya: Women and Musical Mastery in Mali." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 70 (3): 569–602.

(Duga)

pp. 592-3

Certain pieces of music in the jeli's repertoire and certain performance are considered highly powerful and should only be performed by a ngara, who alone can control the strong forces in the words and melody. A younger, unqualified musician who attempts to perform such pieces takes great personal risk. Of course, certain types of occasion are much more likely to invoke the powers of ngaraya than others, such as ritual occasions.

Probably the best known examples of this are the two pieces Janjon and Duga, because they are associated with the battlefield or the hunt, i.e. human or animal slaughter, which releases large quantities of nyame.

The song Duga is, according to Bird:

the oldest and most widespread song in West Africa, recorded in early Arabic texts. It is a praise song for warriors and hunters celebrating heroism ... it was sung by Bakoroba Kone, an elderly bard in Segou, in April 1968, accompanied by two female singers, Penta Dante and Hawa Kone, who sang the song inserted at intervals in the epic recitation (Bird 1972b: 469).

Sidiki Diabate says of this piece:

Duga Keita was very brave, his half-brothers were jealous of him. He sacrificed a cow in the village for brave men. Duga took the head, shoulders and legs because he was the head, shoulders and legs of the army.

He was a great fighter, his name was Duga, at the battle of Samanyana, in the fourteenth century. In this battle all the soldiers were killed, only he survived, surrounded by lots of dead bodies. When older women, the ngaraw, sing this song, the vultures descend. This is why only certain people may sing it. It's very old, only played in battle. When it's played people don't clap, they scrape their swords together (interview, London, June 1987).

Fula Flute. 2008. Mansa America. Completely Nuts.

(Douga)

Epic song about the mythical vulture, a bird that transmutes dead flesh into energy to fly very high. A piece that is played for very powerful people, such as, in this case, President Obama.