janjon

Diabate, Massa Makan. 1970. Janjon, et autres chants populaires du Mali. Paris: Présence Africaine.

(Janjon)

pp. 43–52

Janjon, c'est la peur que tout guerrier doit ressentir avant la bataille.

Janjon, c'est aussi la victoire sur l'ennemi.

Janjon, c'est enfin la victoire sur la peur et sur l'ennemi, c'est-à-dire le triomphe.

Cette chanson qui est l'une des plus populaires du Mali est attachée à la mémoire de Fakoli-kunba, Fakoli-da-ba, compagnon d'armes de Sun Jata, fils de Kanduba Kante et neveu de Sumangurun.

Mais lentement, le Janjon a évolué. Il a cessé d'être un faasa (1) pour devenir la chanson consacrée à ceux qui se sont distingués par des actions d'éclat.

« Sourire à son ennemi

Ne met pas fin au combat.

Se devertir avec son ennemi

Ne met pas fin aux hostilités.

Je te salue O grande peur

Des soirs de bataille !

Fakoli a dansé le Janjon

Devant la foule accourue

Sur la place du Mande.

Je te salue O triomphateur

Des soirs de bataille ! »

Fakoli-Kun-ba est entré au Mande avec trente-trois têtes d'oiseaux accrochées à son bonnet.

Fakoli-da-ba est entré au Mande avec trente-trois peaux de lion. Et il n'était ni sorcier ni génie...

Il avait une grosse tête, Fakoli. Et il était fier.

Il avait une grande bouche, Fakoli. Mais il fallait lui arracher les mots comme à un enfant qui balbutie.

Son père, il ne l'avait pas connu. Quand sa mère l'attendait, un être étrange se présenta à son oncle.

« Sumangurun, roi de Soso, dit-il, l'enfant que ta soeur Kankuba porte est le mien. Appelle-le Fakoli.

Il aura une grosse tête pour être fier. In aura une grande bouche ; mais le vent n'emportera jamais les mots qui s'échapperont de ses lèvres. Et si tu sais y faire, Sumangurun, il t'aidera à étendre ton royaume jusqu'à la mer. »

Fakoli-Kun-ba est entré au Mande avec trente-trois têtes d'oiseaux accrochées à son bonnet.

Fakoli-da-ba est entré au Mande avec trente-trois peaux de lion. Et il n'était ni sorcier ni génie...

Dans le grand vestibule du Mande, Sogolon-man, entouré de ses chefs de guerre, écoutait une nouvelle chanson que les griots avaient composée en son honneur. Et ce qu'elle disait soulevait tous les coeurs :

« Sourire à son ennemi

Ne met pas fin au combat.

Se divertir avec son ennemi

Ne met pas fin aux hostilités.

Je te salue O grande peur

Des soirs de bataille.

Sun Jata a dansé le Janjon

Devant la foule accourue

Sur la place du Mande.

Je te salue O triomphateur

Des soirs de bataille. »

Un étranger vint s'arrêter devant le seuil. Il salua et avant d'entrer, baissa la tête de peur qu'elle ne heurte le linteau.

Toute l'assistance se mit à rire.— L'Etranger est bien petit, dit Balla Faseke Kuyate. Kala Jata, L'homme le plus grand du Mande, entre dans ce vestibule sans avoir à se baisser. L'Etranger pourrait expliquer... Sun Jata lui coupa la parole.

— Fakoli-Lun-ba, Fakoli-da-ba, dit-il, ton message m'est parvenu. Mais avant de t'accepter dans mes rangs, j'ai bien envie de poser une question. Pourquoi embrasses-tu mon combat contre ton oncle ?

— Tu le sais, et tu le demandes ?

L'étranger fit volte-face et sortit de la case. Et à nouveau il s'inclina en regardant le linteau.

Sun Jata se leva avec empressement. Il ne put dominer son émotion quand il dit :

— Ma langue a causé bien du mal, et si mes paroles ne peuvent te soulager, alors exige de moi, Fakoli. Que veux-tu en réparation ?

— Cette chanson qui te glorifie flatte mon oreille. Je la voudrais pour moi seul.

— Au Mande on chante non l'homme mais ses exploits. Je m'en vais déroger à cette coutume pour toi, Fakoli.

L'homme-à-la-gros-se-tê-te, à-la-gran-de-bou-che se mit à rire si fort que le toit du vestibule en trembla.

— Des exploits, dit-il ironique ; des exploits encore, des exploits toujours...

« [Chanson (à Sun Jata)] »

Dans le grand vestibule du Mande, les nkoni pincés par des doigts malicieux se plaignaient en notes discrètes. Elles s'échauffaient, furtives ; montaient dans l'air torride de la case en tournoiments courroucés. Ce n'étaient plus des notes, mais un cri de haine qui, loin d'accepter la lassitude, s'ouvrait sur deux issues, la mort ou le triomphe.

Tira Magan ni Kankejan du revers de la main essuya la sueur grave de son front. Sila Magan souriait en trembalant de tout son corps. Mande Bukari se leva, la tête dans les mains et se dirigea vers la porte. Sun Jata le retint par le bras ; à la vue des larmes qui obscurcissaient les yeux de son frère, il ordonna que la musique s'arrêtât.

Le silence s'établit ; un silence sec, un silence étouffant. La voix de Sogolonman le brisa.

— Trois fois, nous avons affronté Sumangurun, trois fois il nous a refoulés. Après la première défaite nous avons fondé Nyani pour y arbiter notre deuil. A la seconde bataille Sumangurun nous a chassés à nouveau. Désespérés nous avons créé Gnongonson, la ville de la solidarité. Riches de notre deuil, de notre solidarité, nous avons livré un troisième combat, et la chance s'est détournée de notre cause. Sobeya est une ville à l'image de notre espoir en une victoire future...

Nyani ! s'écria le fils de Sogolon, Nyani dit notre souffrance. Nyani fait revivre tous les braves qui sont morts. A Gnongonson nous sommes restés unis et fiers malgré la défaite. Demain nous partons de Sobeya pour affronter Sumangurun. Que dis-je, Sumangurun ! N'est-il pas invisible sur le champ de bataille ? N'gana jibrila est notre ennemi. A chaque rencontre il a tué quarante de nos braves compagnons.

Un rire fusa provenant de la pénombre, et Sun Jata vit des yeux luisants qui le fixaient comme deux braises ardentes.

— N'Gana Jibrila, reprit-il. Cet homme est un dèmon !

Le rire repartit, ironique ; il se gonfla lentement et toute la case trembla.

— N'Gana Jibrila...

— Et moi, Jam-jam Koli, fils de Kankuba Kante, je jure de tuer N'Gana Jibrila demain sur le champ de bataille.

A nouveau se fit le silence ; un grand froid pénétra la case balayant l'air torride. Tous les chefs de guerre se levèrent en un seul bond. Tira Magan ni Kankejan comme foudroyé tomba à la renverse sur sa lance.

— Il m'a devancé, criait-il, je dis qu'il m'a devancé... Sila Magan, de colère, planta la sienne dans le mur. Mande Bukari cria à l'imposture, à la fanfaronnade.

— Qui promet de vêtir un éléphat fait une grande promesse, dit le fils de Sogolon.

— Et s'il la réalise ?

— Il fait un acte digne d'éloges.

Fakoli-Kun-ba, Fakoli-da-ba s'amusa de cette repartie. Ensuite il fit des gestes de la main comme pour saisir le fil de ses mots, et posa sur Sun Jata un regard énigmatique.

— Fils de Sogolon, dit-il, permets que je me rétracte.

— La parole, Fakoli, c'est comme l'eau. Versée, elle ne se ramasse pas. Mais au Mande, pour l'étranger, nous transgressons volontiers nos usages.

Fakoli se leva, ses yeux hors des orbites rivés sur le toit de la case.

— Demain, dit-il, je predrai N'Gana Jibrila vivant sur le champ de bataille.

Et il sortit du vestibule en s'inclinant sous le linteau.

« [Chanson (à Sun Jata)] »

Dans le grand vestibule du Mande, contre tout précédent, un homme autre que Sun Jata imposa le silence.

— Le janjon est-il à moi, fils de Sogolon ? N'Gana Jibrila est là, devant toi, ligoté comme un singe à vendre. Le janjon est-il à moi ?

—Griots, dit Sun Jata, célébrez Fakoli-Kun-ba, Fakoli-da-ba, fils de Kankuba Kante. Mais Balla Faseke Kuyate intervint, un brin de malice accrochée aux lèvres.

— Au Mande, on assimile une belle action à la chance, ironisa-t-il en foudroyant Fakoli du regard.

L'homme-à-la-gros-se-tê-te, à-la-gran-de-bou-che partait d'un rire satanique, quand à l'instant même une flèche entra dans la case, se dirigea sur Sun Jata, le contourna et frappa à mort un des chers de guerre.

— Nyani Mansa Kara, s'écria Sun Jata. Vêtu de fer il se bat à distance. J'ai honte pour Nyani Mansa Kara.

— Et moi, dit Fakoli, demain je tuerai Nyani Mansa Kara.

« [Chanson (à Sun Jata)] »

Un homme bardé de fer parut soudain devant le vestibule. Sun jata se dressa, son sabre dégainé au-dessus de sa tête.

— Nyani Mansa Kara ! Enfin Nyani Mansa Kara accepte le combat à découvert. Mais il n'a pas pris soin d'ôter ses habits de fer...

Le visiteur mystérieux le rassura en déposant ses armes sur le sol, ensuit il entra dans le vestibule en s'inclinant sous le linteau et se découvrit.

—Fakoli... Fakoli a tué Nyani Mansa Kara. Le fils de Kankuba fit mine de ne pas entendre.

—Balla Faseke, dit-il, toi qui connais les usages du Mande mieux que personne, le janjon est-il à moi ?

— Un exploit n'attribue rien au Mande ; deux exploits donnent à penser. Mais le nombre trois est viril.

Fakoli se dirigea vers la porte, s'arrêta sous le linteau en souriant. Il s'étira, s'étira... poussé par sa grosse tête, le toit se souleva lentement et tomba à la renverse.

— Le nombre trois est viril, dit Sun Jata en regardant Balla Faseke.

Les nkoni se mirent à vibrer, plaintives, tandis que Fakoli livrait à lui-même un combat pour recouvrer sa taille d'homme.

« [Chanson (à Fakoli)] »

Ministère de l’information du Mali. 1971. Première anthologie de la musique malienne: 1. Le Mali des steppes et des savannes: Les Mandingues. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2501.

(Janjon)

Janjon sings of the man of action, the man of genius whose name will be written in the book of history. This beautiful Mandingo song is dedicated to the memory of Fakoli-with-the-big-head, Fakoli-with-the-large-mouth. Big head, because he was never afraid even in the heat of a battle; large mouth for having never been afraid to speak the truth—even though it tasted bitter. This legendary hero, whose existence, however, is certain, was a brother in arms of Sunjata. He is a descendant of the Bula and an ancestor of the Cissoko, the Dumbuya and the Kuruma:

You can laugh with your enemy

Without renouncing battle with him.

You can well enjoy yourself with your enemy

Without therefore refusing the fight.

Let us welcome the evening of the great battles,

Opposing great men

Standing upright.

Bird, Charles S. 1972. "Heroic Songs of the Mande Hunters." In African Folklore, ed. Richard Dorson, 275-93, 441-77. Bloomington: Indiana University.

(Janjon)

p. 280

Some of the ritual songs, such as the Janjon, can be danced only by men who have made a major kill, i.e., a lion, an elephant, a bush buffalo, or a man. The Duga is, in some areas, a ritual song for warriors as opposed to hunters and can be daned only by a recognized hero, one who has narrowly escaped death in battle or has killed a man in battle. It is through songs such as these that a sort of hierarchy of excellence is established among the hunters. At the end of the typical ceremony, the hunters gather around and listen to a heroic song sung about great hunters and warriors of the past. These heroic pieces may be of one to two hours' duration and be told in the course of one evening, or, in the case of a ceremony lasting several days, the performance may continue over several evenings, and the total recitation time may run upward of ten hours.

p. 291

It can be claimed that many of the songs incorporated into the epics have their origin as hunters' songs. This is particularly evident in the case of the Janjon and the Duga, both of which are ceremonial dances of high order in the hunters' and warriors' societies.

(Diandion)

p. 219

Le Diandion, air guerrier antérieur au conquérant, dédié par celui-ci à Fakoli, devint ainsi l'air musical des descendants de ce général.

Bird, Charles S., and Martha B. Kendall. 1980. "The Mande Hero: Text and Context." In Explorations in African Systems of Thought, ed. Ivan Karp and Charles Bird, 13-21. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Reprinted Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987.

(Janjon)

p. 19

Physical descriptions of heroes in tbe texts frequently elaborate their nonheroic qualities. Sunjata, for example, is portrayed as crippled and infirm until he overcomes tbe curse placed on him. Fakoli, one of his great generals, is characterized as exceptionally short, with an enormous head and a large mouth. The heroic stature of these men is nevertheless indexed in the nyama-laden objects they carry with them. In the Janjon, the Hero's Dance, these lines describe Fakoli's garb:

He entered the Mande

With skulls of birds

Three hundred three and thirty

Hanging from his helmet.

He entered the Mande

With the skulls of lions

Three hundred three and thirty9

p. 20-1

The Janjon praises the exploits of Fakoli, nephew of Sumanguru, the blacksmith king of the Soso and Sunjata's powerful foe. The Janjon tells how Sunjata wages campaign after unsuccessful campaign against Sumanguru to no avail—until Fakoli comes to join him. When Fakoli enters the camp, he finds bards singing the Janjon for Sunjata. He offers to help Sunjata defeat Sumanguru in exchange for the song, an offer which sends the entire camp into gales of laughter at the diminutive hunter with the huge head and the great mouth. Nevertheless they decide to put him to a test and, therefore, ask him to kill one of Sumanguru's fiercest generals. Fakoli returns the next day with the general's head, asking for his song. Another test is posed, and Fakoli meets it too. This time when he asks for the song, Sunjata's hesitation angers him and his anger swells in him until he grows so large that the roof of Sunajata's hut sits on his head like a bush hat. Recognizing Fakoli's terrible power, Sunjata's bards sing the Janjon for him and the song becomes his forever.

p. 25

9. The extracts of the Janjòn come from a performance by Yaumru and Sira Mori Diabaté in Keyla, Mali, 1972. A literary version of the Janjon is presented in Diabaté (1970).

Knight, Roderic. 1982a. "Manding/Fula Relations as Reflected in the Manding Song Repertoire." African Music 6 (2): 37–47.

(Janjong)

p. 39

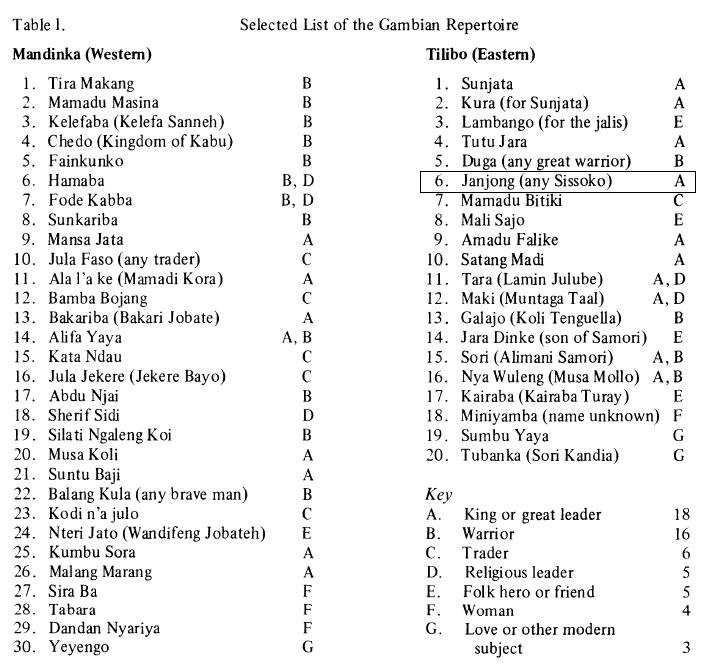

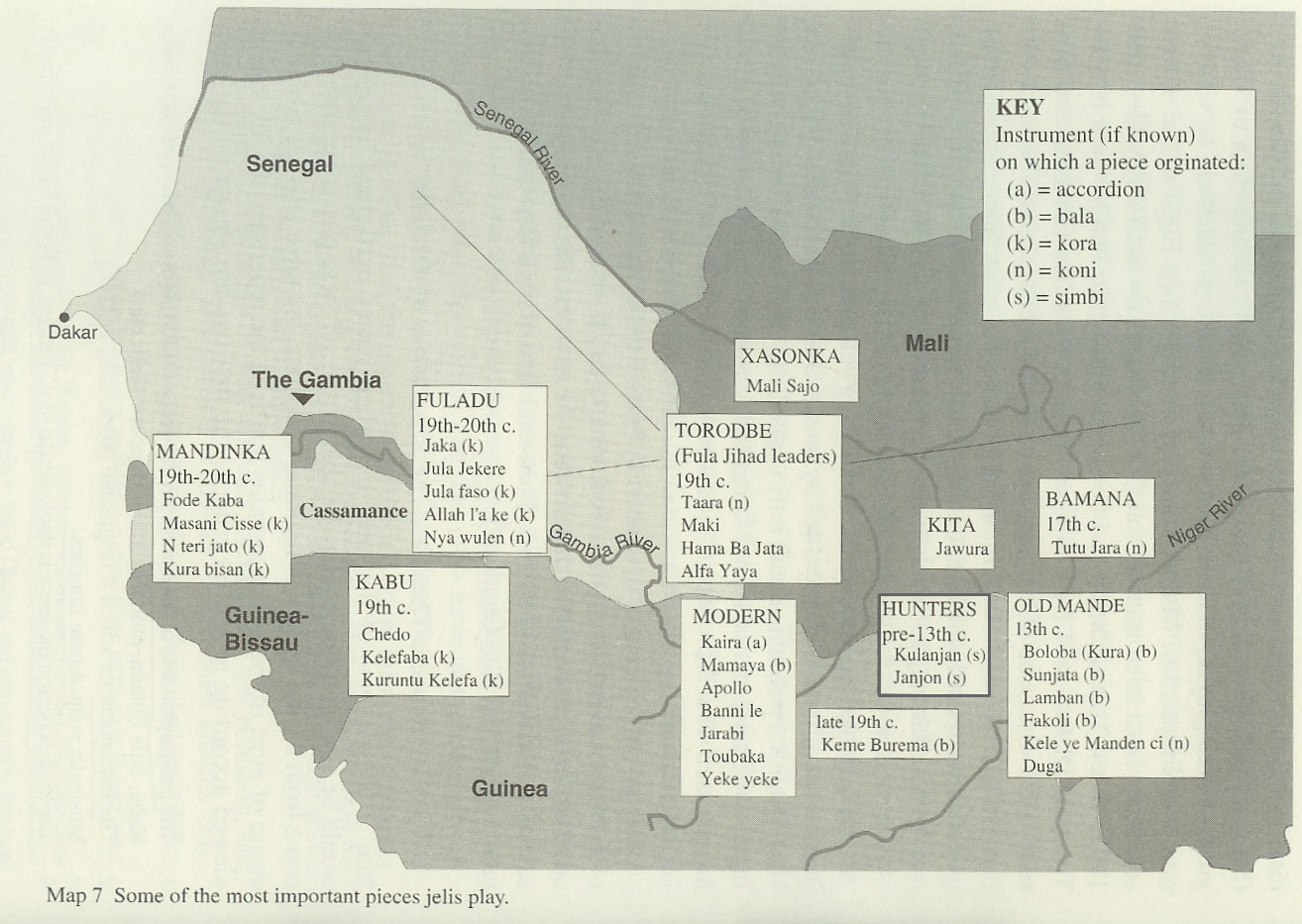

Table One . . . includes the best known, most often heard, or otherwise significant songs in the [Gambian] repertoire. In each column the top few songs are the oldest, and the bottom few are the youngest. The majority in each case fall somewhere in between (often in the nineteenth century), but no chronological ordering beyond this is intended, since it is often not possible to date a song exactly. Most of the songs bear the name of their owner as the title. Where they do not, his name is shown in parentheses next to the title. The letter code at the right represents the person's "claim to fame" or calling in life, as shown in the bottom of the list.

p. 40

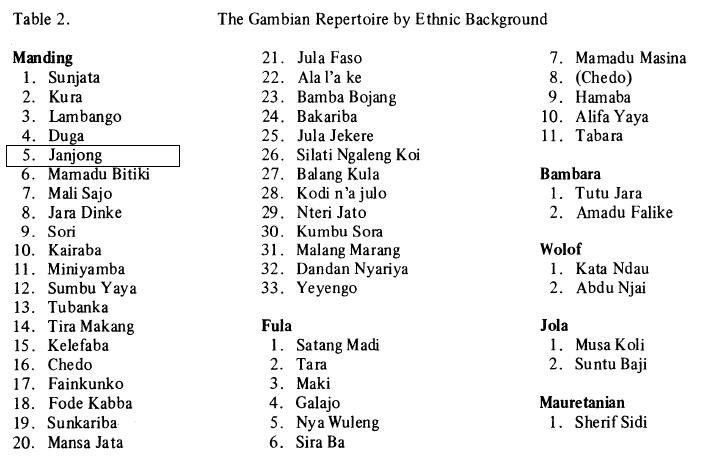

Table Two shows the same fifty songs again, grouped this time by the ethnic background of the people commemorated.

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Janjungo)

pp. 146–59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Janjungo (Janjon, Janjumbaa) |

| Translation: | expedition |

| Dedication: | Sora Musa Suso, any Suso or Sissoko |

| Notes: | a.k.a. Janjon, Janjumba |

| Calling in Life: | King or Leader, Warrior |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | E (13th & 14th c.) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

Haydon, Geoffrey, and Dennis Marks, dirs. 1984. Repercussions: A Celebration of African American Music. Program 1. Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia. Chicago: Home Vision.

(Janjumbaa)

Aamadu Jeebaate demonstrating a piece called Janjumbaa originally played on the konting, an older Mandinka instrument.*

SJ: Is this an adaptation from the konting?

AJ: That's how it was played on the kontingo. A new piece, Jula Jekere has been derived from it.

* Transcription mine. Orthography based on Jatta (1985).

Knight, Roderic. 1984. "The Style of Mandinka Music: A Study in Extracting Theory from Practice." In Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, vol. 5, Studies in African Music, ed. J. H. Kwabena Nketia and Jacqueline Cogdell Djedje, 3–66. Los Angeles: Program in Ethnomusicology, Department of Music, University of California.

(Janjon)

p. 11

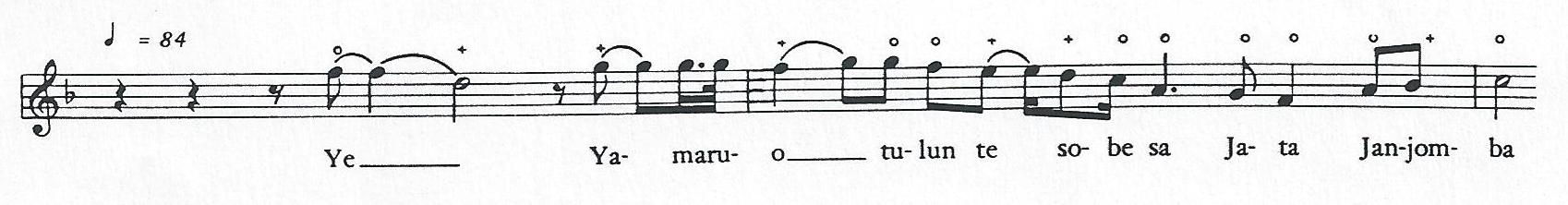

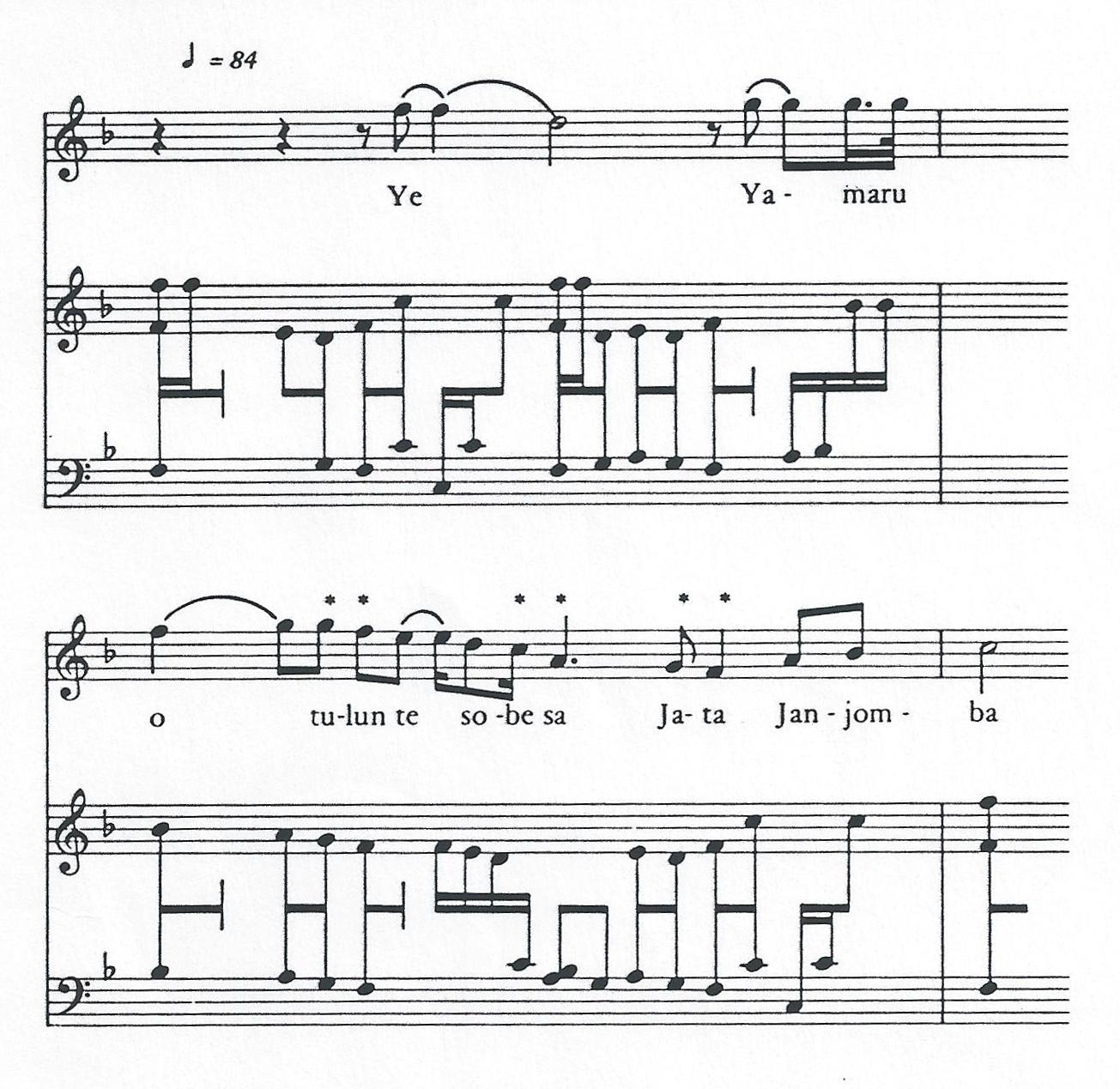

. . . "Janjon," a Tilibo song of bravery, with the text, "Yamaru-o, a little play doesn't dampen the resolve of the Lion on a great campaign."

p. 12

Example 4. A donkilo line from "Janjon" (Transcribed from BM 30L 2501, A-5)

p. 16

We have seen an example of a donkilo melody in the principal Hardino mode. It is "Janjon" (Ex. 4).

p. 20–21

In another type of derivative kumbengo the instrumental part is independent much of the time, but at certain points its relation to the donkilo becomes clear. An example of this type is "Janjon," where the kumbengo is the same length as the donkilo (even a little longer) and clearly related at several points (see Ex. 12).

Jatta, Sidia. 1985. "Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia." In Repercussions: A Celebration of African-American Music, ed. Geoffrey Haydon and Dennis Marks, 14–29.

(Janjumbaa)

p. 23

Jula Jekere was, according to Aamadu Jeebaate, derived from an older piece called Janjumbaa. The latter piece is said to have been composed for persons bearing the patronym Suusoo . . .

Conrad, David C. 1989. "'Bilali of Faransekila': A West African Hunter and World War I Hero according to a World War II Veteran and Hunters' Singer of Mali" History in Africa 16: 41-70.

(Janjon)

p. 59

13

janjon: This is both a dance that can be performed only by heroes who have faced grave danger, especially in battle, and a song that can be sung only to those heroes.

14

"janjon is not easy:" No two versions of janjon are alike, but certain lines, such as this one, appear in more than one variant, e.g., Nanténéjé Kamissoko sings:

Janjon is not easy,

Janjon is not easy,

Those who speak of it will suffer.

[Bamako, 21 July 1975]

In this case Seydou refers not directly to the janjon, but to war itself, the dangerous thing that leads to dancing or singing janjon.

p. 61

48

Here Seydou refers to an especially bad time when people suffered and died, that is, a time that might have produced (or was badly in need of) heroes qualified to dance the janjon or to hear it sung in praise of themselves.

Kouyate, (El Hadj) Djeli Sory. 1992. Guinée: Anthologie du balafon mandingue. Vol 2. Buda, 92520-2.

(Djandjon)

Dédié aux grands chefs de guerre victorieux.

Kaba, Mamadi. 1995. Anthologie de chants mandingues (Côte d'Ivoire, Guinée, Mali). Paris: Harmattan.

(Djandjon)

pp. 106-7

IL Y A DES CAILCEDRATS EN AMONT

(DJALA YE KOSSANDO)

Il y a des cailcédrats en amont

Il y a des cailcédrats en aval

De la grande rivière !

Ils sont de tailles différentes

Et de grosseurs différentes !

Mais ils ont tous la même saveur,

La saveur amère du cailcédrat !

Cailcédrat oh ! Cailcédrat !

Le cailcédrat de Ia liberté

N'est jamais échangeable

Et n'est jamais négociable !

Nous, nous sommes sans peur.

Le chant sacré du vautour

N'est pas chanté pour les poltrons

Qui fui ent devant l'ennemi

Et transpercent l'espace.

CHOEUR

Oh, Yamery le vautour !

Le fuyard ne danse jamais

Le chant du vautour !

Car l'homme ne doit jamais

Fuir devant sonsemblable [sic]

Et le brave ne doit jamais

Manger la viande du vautour.

Dans la caverne aux hyènes

Aucunhomme [sic] ne peut entrer

Dans la caverne aux hyènes

S'il est un homme poltron 1 !

1 1 Le chant du vautour est aussi un des grands classiques du Manding. Ce chant est aussi couramment dénommé "Djandjon", c'est-à-dire, le combat opiniâtre corps à corps ou la mêlée. Il a été composé en l'honneur de Samory, au moment où celui-ci, harcelé par les troupes françaises conquérantes, s'adonnait à la guérilla parce qu'il était traqué de tous côtés. On sait que l'Almamy Samory, après avoir conquis un vaste empire en Afrique Occidentale et surtout dans les pays malinké de Guinée française, du Soudan français ou actuel Mali et de Côte d'Ivoire dut faire face aux troupes françaises bénéficiant de capacités colossales en matériel militaire et humain et d'énormes moyens financiers, économiques, marchèrent techniques et psychologiques. Le 7 mai 1889, ces troupes sur Kankan. Et Samory, informé de cette marche, donna l'ordre de mettre le feu à cette ville. Et de guérilla en guérilla, il dut s'enfoncer en Haute Côte d'Ivoire où il fut capturé à Guélémou en septembre 1898. Puis, il fut exilé au Gabon où il mourut en 1900. Le brave danse le chant du vautour, mais ne mange pas la viande du vautour par égard pour cet oiseau qui dévore les braves morts sur le champ de bataille.

Ce chant d'expression animiste a été aussi entonné au temps de Samory. C'est un chant de bravoure et destoïcisme, un chant patriotique qui résiste au temps.

Kouyaté, Sory Kandia. 1999. L'épopée du Mandingue. Mélodie, 38205-2. Re-issue of 1973, SLP 36, SLP 37 and "Toutou diarra" from SLP 38.

(Dyandjon)

Vieil hymne de guerre du Mandingue dédié au Chef des Forgerons, général de l'Empereur Soundiata Keita, le sorcier Facoli Koroma.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Janjon)

p. 82

Although Wasulu music has made a significant impact on a national Malian musical identity in the past decade, . . . Maninka simbi music has had a more far reaching impact on western African music, most likely because of the spread of Maninka culture. Three pieces in particular, commonly believed to have originated on the simbi, have gained widespread currency: Janjon, Kulanjan (Long-crested eagle), and Balakononifin (of Balakononinfin; Little black bird of the river.)

pp. 83–84

Ritual songs, such as Janjon and Duga, are related to the hunt and are restricted to those who have earned a reputation. . . .

The significance of ritual songs is still maintained in Mande society and widely respected.

Janjon, for example, is exclusively reserved for hunters who by their coolness, their fearlessness, or their courage have triumphed over their "enemies" or escaped a danger. "Who can dance Janjon before having seen a calamity!" says the refrain of this hymn. . . . (Y. Cissé 1994:54)

In a rare film scene showing hunters dancing to Janjon, Salif Keita (Austin 1991-vid) calls it the most sacred of pieces and says he had to request permission to dance. He is shown dancing later, but to another piece, Balakononifin, not Janjon. Janjon is associated with the great warrior Fakoli, who left the side of his uncle Sumanguru Kante to join the ranks of Sunjata, and it is sometimes sung during renditions of the Sunjata epic when Sumanguru Kante makes an appearance. Kulanjan, also known simply as Donso foli (Hunter's music), has no associations outside hunting as Janjon does. Janjon and Kulanjan form the oldest layer of the jeli's repertory.22

19. . . . For transcriptions of lyrics to . . . Janjon, see Y. Cissé (1994:148–52.)

22. For an extended discussion of Fakoli see Conrad (1992). For more on Janjon see Bird (1972:280,291), Bird and Kendall (1980:20–21), and M. Diabate (1970a:43–52). Bird and Diabate worked together in the middle to late 1960s (Bird 1972: 441), so their publications in the early 1970s are probably based on a common pool of research. According to Soninke griot Diarra Sylla (Dieterlen and Sylla 1992: 14, 96), Janjon was sung in honor of Dinga, the founding ancestor of the Soninke empire Wagadu. Sidiki Diabate (1990-per: 15–18) attributed Janjon originally to Sumanguru's ancestor Sora Musa, and then to Sumanguru, finally taken over by Fakoli. A line from Janjon in praise of Sumanguru Kante, "First king of the Mande, And traditional King," has prompted Bird (forthcoming) to suggest the idea of a song's being captured. Bird and Kendall (1980:20–21) relate that Janjon was first sung in praise of Sumanguru Kante, and that on hearing it sung for Sunjata, Fakoli desired and ultimately won it because of his heroic sacrifices. "They [jelis] sing that Sumanguru is the first and traditional king; they say that Sunjata is. This sounds like good evidence for Sunjata's winning the song, and having its accompanying story adapted to tit the new circumstances, but the bards choose to preserve Sumanguru's original claim to the title, and they preserve the role of Fakoli as earning the right to the song" (Bird, forthcoming). The praises of Sumanguru were perhaps retained because "the hero's greatness is measured against that of his adversaries. . . . The more that is said of the terribleness of Sumanguru, the more terrible had to be the greatness of Sunjata who defeated him" (Bird, forthcoming). Bird uses this idea of transfer of song ownership to support his suggestion that Sunjata might have been a Soninke native son from Mema in the north who imposed himself militarily on the Mande to the south, defeating Sumanguru Kante. Bala Faseke Kouyate, who would have been Sumanguru's jeli, then helped legitimize the new ruler by singing Janjon for Sunjata. Furthermore, Bird sees this as symbolizing the victory of northern horsemen over blacksmith-earth priests farther south in the savanna.

pp. 87–89

(See Charry.) (Simbi transcriptions w. discussion.)

p. 89

26. A rare early musical transcription of a "Mandingo Air" (Moloney 1889:279, no.2) has a melodic profile that looks very much like Janjon or its Senegambian musical descendant Jula Jekere.

p. 148

p. 149

The simbi is sometimes cited as the ultimate source of the jeli's repertory, contributing pieces such as Janjon and Kulanjan.

p. 150

The parent-child relationship of some pieces is common knowledge and is readily talked about as such among many musicians: Saxo (Sacko) Dugu comes from Duga; Jula Jekere from Janjon; and Jaka from Hama Ba Jata.

p. 151

Salif Keita (1991-disc) has taken one of the oldest pieces in the repertory, Janjon, and transformed it with new words, a new title (Nyanafin), and no reference to the original except the musical accompaniment. The same has been done by Baaba Maal (1991-disc), who took Jula Jekere (an important piece from eastern Gambia), which itself is a transformation of Janjon, changed the words, and retitled it Joulowo. They both took pieces that were important in their own countries: Janjon from old Mali for Salif Keita, and Jula Jekere from eastern Senegambia for Baaba Maal.

p. 152

Simbi Pieces: Janjon and Kulanjan (also known as Donso fòli) belong to the oldest layer of the jeli's repertory.

During a performance of Sunjata fasa a number of distinct songs praising Sunjata may be incorporated . . . Songs praising other figures in the epic might be incorporated, such as Janjon, Boloba, and Tiramakan.

p. 163

(See Charry, 2000.) (Discussion of koni tunings.)

pp. 398–401 (Appendix C: Recordings of Traditional and Modern Pieces in Mande Repertories)

Simbi: Janjon

Nantenedie Kamissoko (Ministry of Information of Mali, 1971, vol. 1)

Sory Kandia Kouyate ([1973] 1990)

Les Ambassadeurs (1976b, 1979a)

Bembeya Jazz (n.d.)

Ami Koita (Idjodo, 1986)

Kandia Kouyate (Dalla, 199?)

Baaba Maal (Joulowo, 1991)

Salif Keita (Nyanafin, 1991)

Lamine Konte (1990)

Diabate Family of Kela (1994)

Keletigui Diabate (1996)

Moussa Keita (1997?)

Diabate, Mamadou. 2000. Tunga. Alula.

(Djanjo)

A name for an African shaman, someone who communicates with the spirits. This song goes back to the time of Sunjata Keita, the 13th century. Mamadou says, "You must have done something very brave, such as fighting in a war, in order to have a jeli sing this song for you."

Fula Flute. 2002. Fula Flute. Blue Monster.

(Djandjou)

This is a deep, ancient, noble epic song. It is usually performed for high dignitaries, aristocracy and otherwise powerful people and evokes much emotion for Malians in particular.

(Janjon)

Another song of the Sunjata Epic cycle of the founding of the Empire of Mali, about the heroic struggle of Sunjata Keita. Janjon is a term for a popular dance rhythm.

| Jan jonba, jan jonba dòn kelu ooh... Jan jonba dòn kelo wo ooh, Jan jon ne nindi. Nin fora bula mansa si soluyé: Soro bula Fakoli den, Baya bila Fakoli den, Bati bila Fakoli den, Batimanan bila Fakoli den, Deme nyòa gon ye Fakoli féli. Ani Dionara koladan na fòlò fòlò? Siramanba Koita le nin masòsòdio, Turaman Nin Kante Jan, Muke Mussa, A Nin Muke Datuma: Ani woluka koladò fòlò fòlò N'néyé Nin yòrò fòla. Fakoli Kumba, Fakoli Daba... | Janjon dancers, janjon dancers, Dance to the rhythm of janjon. This rhythm was played for the chief with five names: Great-great-grandson of Soro Bula Fakoli, Great-grandson of Baya bila Fakoli, Grandson of Bati Bila Fakoli, Son of Batimanan Fakoli, Fakoli the Protector. With whom did he first collaborate? With Siramanba Koita, the righteous, With Turaman Nin Kante Jan, beyond reproach, The brothers Muke Mussa and Muke Datuma: they all were together from the beginning. When I say this, I speak of Fakoli the proud, Fakoli the Speaker of Truth ... |

Durán, Lucy. 2007. "Ngaraya: Women and Musical Mastery in Mali." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 70 (3): 569–602.

(Janjon)

p. 589

Throughout the 1970s Batourou Sekou was the regular accompanist to the singer Fanta Damba cini. . . . I asked Batourou Sekou about their distinctive version of Bajuru (also known as Tutu Jara), a version which reputedly "drove people mad" and which created a whole new style of performance in Bamako from the 1970s.

I used to listen to two kora players in Kita, when they played this piece I went crazy ... my Tutu Jara is just how Fanta Damba sings it. Tutu, Lamban, Sunjata and Janjon, those are the most important tunes. People can play Janjon until the morning. Some women sing it until they're blind. Ngaraya kills you slowly.

p. 592

Certain pieces of music in the jeli's repertoire and certain performance are considered highly powerful and should only be performed by a ngara, who alone can control the strong forces in the words and melody. A younger, unqualified musician who attempts to perform such pieces takes great personal risk. Of course, certain types of occasion are much more likely to invoke the powers of ngaraya than others, such as ritual occasions.

Probably the best known examples of this are the two pieces Janjon and Duga, because they are associated with the battlefield or the hunt, i.e. human or animal slaughter, which releases large quantities of nyame. Janjon originally commemorated Fakoli Doumbia, one of Sunjata's generals, and is also a hunters' song. "Some of the ritual songs, such as the Janjon, can be danced only by men who have made a major kill. i.e. a lion, an elephant, a bush buffalo, or a man" (Bird 1972a: 280). Janjon is also the only jeli piece that may be performed at the funeral of another jeli: for example, it was sung at the state funeral of Sidiki Diabate in Bamako in October 1996.