jula jekere

Suso, Foday Musa. 1978. Kora Music from Gambia. Folkways, FW 8510. Reissued in 1990. Smithsonian Folkways, 08510.

(Jula Jekere)

Hardino tuning.

This is a traditional and very popular song commemorating a wealthy trader (jula) named Jekere Bayo who lived in The Gambia in the last century. He was so wealthy and powerful that many stories have grown up around him. One relates how he decided that instead of observing the traditional prayers at the end of Ramadan (Muslim month of fasting) he would stage his own prayer service a week later and he sent his jalis to spread this information to the neighboring kings. Another, related by Suso, tells of his extravagant sacrifice for the feast following these prayers of 100 sheep, 100 cows, 100 goats, 100 camels, and 100 horses. Only the intervention of his jali singing this song for him prevented him from sacrificing 100 slaves as well.

Knight, Roderic. 1982a. "Manding/Fula Relations as Reflected in the Manding Song Repertoire." African Music 6 (2): 37–47.

(Jula Jekere)

p. 39

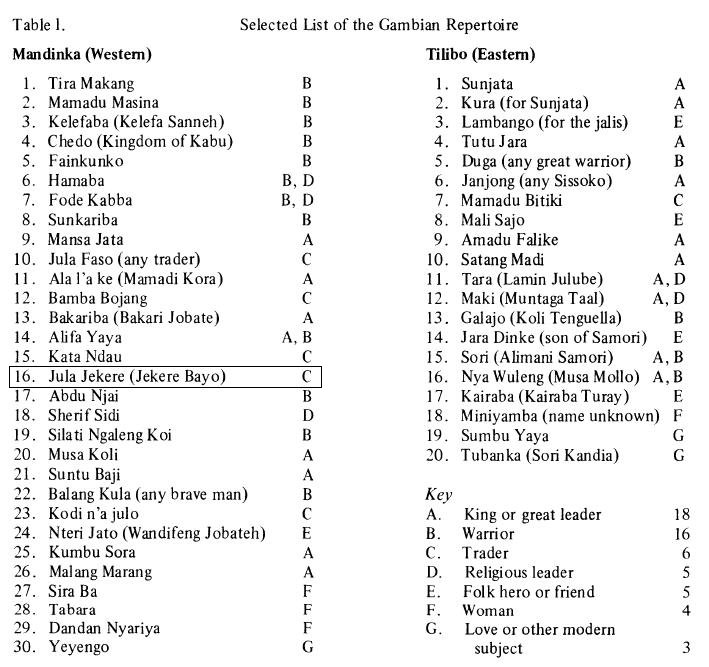

Table One . . . includes the best known, most often heard, or otherwise significant songs in the [Gambian] repertoire. In each column the top few songs are the oldest, and the bottom few are the youngest. The majority in each case fall somewhere in between (often in the nineteenth century), but no chronological ordering beyond this is intended, since it is often not possible to date a song exactly. Most of the songs bear the name of their owner as the title. Where they do not, his name is shown in parentheses next to the title. The letter code at the right represents the person's "claim to fame" or calling in life, as shown in the bottom of the list.

p. 40

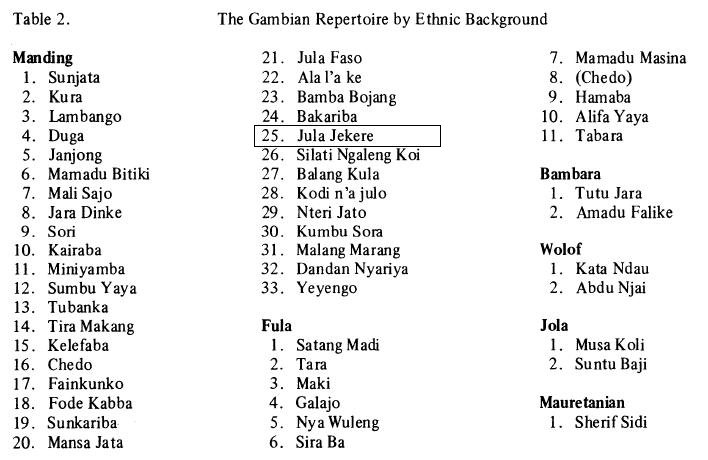

Table Two shows the same fifty songs again, grouped this time by the ethnic background of the people commemorated.

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Jula Jekere)

pp. 77–80

Donkilo (on teaching tape)

| Kele, i Kamara wo kele | Fight Yamaru, oh fight. |

| Jula Jekere be salila nyinang | Jula Jekere is praying this year. |

Additional words (from Knight 1973, 2:6)

| Ye Yamaru O kele | Ye Yamaru O fight. |

| Jula Jekere be salila | Jekere the trader is praying, |

| Ali ta fo [Wuli/Nyani] Mansa ye | You all go tell the king of Wuli (Nyani) |

| Jula Kumbuna be salila nyinang | Trader Kumbuna is praying this year |

Related Information

Jula Jekere was a wealthy trader (jula = trader), who as a flamboyant gesture, decided to celebrate Ed El Kabir, Tobaski, a Muslim feast, ten days later than usual. He offered large sums of money to the kings of the area to ensure their cooperation in celebrating the prayer day and feast on a different day. His jalis announced: "Go tell the mansa of Wuli, Jekere will pray this year." It was reported that he sacrificed over one hundred sheep, one hundred cows, one hundred goats, and one hundred horses as an extravagant gesture to celebrate the end of Ramadan. In spite of his show of wealth, the festival reverted to its correct time.

Knight prefers the use of a numeric notation only. He suggests that the beginning pattern doesn't "sound" in your mind as it should if the bar lines are aligned with the other kumbengos: therefore he has placed them differently, (RK, letter to the author, April 25, 1984).

pp. 146–59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Jula Jekere |

| Translation: | Jekere, the trader |

| Dedication: | Jekere Bayo |

| Notes: | a.k.a. Jarabi Kura |

| Calling in Life: | Trader |

| Original Instrument: | Kora |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | M (19th & 20th c. up to WWII) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

| Title | Jarabi Kura (Jula Jekere) |

| Translation: | New Lover |

| Dedication: | n/d |

| Notes: | a.k.a. Jula Jekere |

| Calling in Life: | n/d |

| Original Instrument: | all |

| Region of Origin: | Gambia |

| Date of Origin: | L (after WWII) |

| Sources: | 1, 5 (Jessup & Sanyang, M. Suso) |

Haydon, Geoffrey, and Dennis Marks, dirs. 1984. Repercussions: A Celebration of African American Music. Program 1. Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia. Chicago: Home Vision.

(Jula Jekere)

Aamadu Jeebaate demonstrating a piece called Janjumbaa originally played on the konting, an older Mandinka instrument.*

SJ: Is this an adaptation from the konting?

AJ: That's how it was played on the kontingo. A new piece, Jula Jekere has been derived from it.

* Transcription mine. Orthography based on Jatta (1985).

Jatta, Sidia. 1985. "Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia." In Repercussions: A Celebration of African-American Music, ed. Geoffrey Haydon and Dennis Marks, 14–29.

(Jula Jekere)

p. 23

Not all the pieces in the repertoire bear personal names as their titles, but most of them are named after the personalities for whom they were originally composed. Some examples of these are: FodeKabaa, Kelefaa, Saane, Saamoori, Alfaa Yaayaa, Mammadu Maasina, Satan Madi, Sirifu Siidi and Jula Jekere, all of which bear the names of historic figures.

Jula Jekere was, according to Aamadu Jeebaate, derived from an older piece called Janjumbaa.

Jobarteh, Amadu Bansang. 1993. Tabara. Music of the World, CDT 129.

(Jula Jekere)

This song commemorates events in the life of a wealthy and powerful jula. As with Jula Faso, Amadu uses this song as a vehicle for praising his own friends and patrons. The humming so characteristic of kora music is heard throughout this piece. The music for Jula Jekere is believed to have originated from an old praise song named Janjon.

Suso, Foday Musa, and Bill Laswell. 1997. Jali Kunda: Griots of West Africa and Beyond. Ellipsis Arts, CD3511.

(Jula Jekere)

The man whom this song is named for, Jula Jekereh Bayo, also came from a trader family. He was quite wealthy, and wanted to host his own festival to celebrate the end of Ramadan. He decided to kill many things he owned for the feast, including 100 lambs, 100 goats, 100 chickens and 100 cows. He also planned to kill 100 men. His brother tried to stop him, but was unsuccessful in his plea, so he went to the Griots for their help.

At the brother's urging, two Griots—Nyamen Lamin and Nyamen Karunka (ancestors of Foday Musa Suso)—tried to convince Jula Jekereh to let the people go. At night after dinner they took their instruments to Jula Jekereh's house, and began to play this song:

"Jula Jekereh, Jula Jekereh,

You are the greatest, richest person in this area.

Tomorrow is your festival.

Please kill the animals, but let the people go."

Jula Jekereh said, "I like what the Griots are saying. I will release the human beings." And this became Jula Jekereh's song.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Jula Jekere)

pp. 38–39

The people of Ghana probably spoke Soninke, the northernmost branch of the large Mande language family. . . . Soninke dispersed, with some establishing long-distance networks as traders. These traders, called Wangara in Arabic sources or Jula by the Maninka, were also well versed in Islam owing to their contact with Muslims coming from across the Sahara, and they were instrumental in spreading Islam in West Africa.

p. 53

Garankelu are probably of Soninke origin and may have been part of the long-distance migrations of Soninke traders (Jula) and clerics (Mori) in search of new clients, supplying leather goods such as amulet cases, beginning in the eleventh or twelfth century.

p. 89

26. A rare early musical transcription of a "Mandingo Air" (Moloney 1889:279, no.2) has a melodic profile that looks very much like Janjon or its Senegambian musical descendant Jula Jekere.

p. 133

Long-distance Soninke merchants known as Wangara or Jula may have been responsible for the distribution of gambare-derived names farther east.

p. 148

p. 150

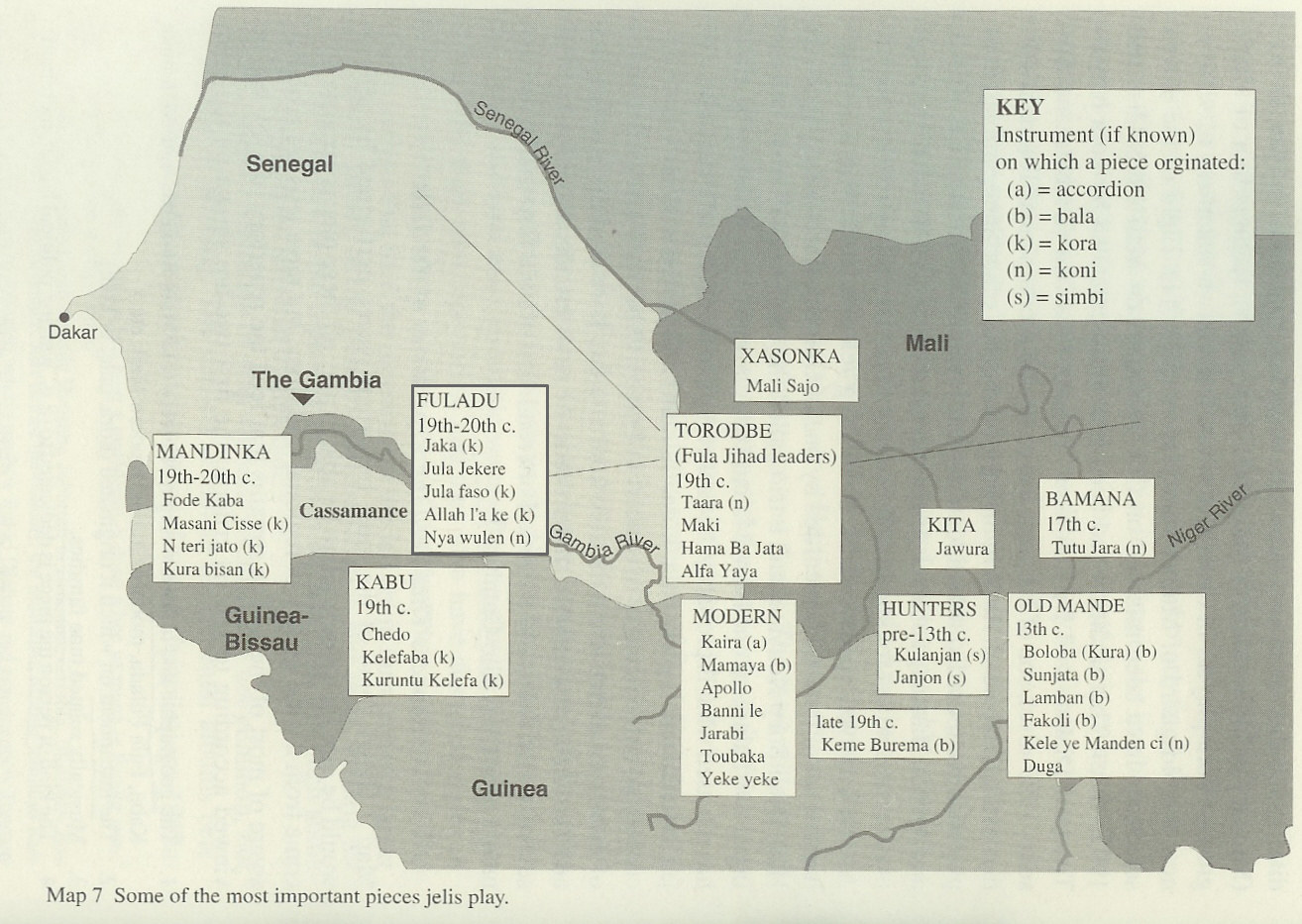

The parent-child relationship of some pieces is common knowledge and is readily talked about as such among many musicians: Saxo (Sacko) Dugu comes from Duga; Jula Jekere from Janjon; and Jaka from Hama Ba Jata.

p. 151

Baaba Maal (1991-disc), . . . took Jula Jekere (an important piece from eastern Gambia), which itself is a transformation of Janjon, changed the words, and retitled it Joulowo.

Diabate, Toumani, and Sidiki Diabate. 2014. Toumani & Sidiki. World Circuit, WCD087.

(Jula Jekere)

This Gambian song, from about a century ago celebrates the generosity of a merchant called Jula Jekere at a memorable Tabaski (the feast that follows the fasting of Ramadan). It is played in an obscure tuning from eastern Gambia called 'Tomora Meseng' which has a bluesy feel that Toumani describes as "very melacholic, soft and sentimental."