keme burema (sori)

Diabate, Massa Makan. 1970. Janjon, et autres chants populaires du Mali. Paris: Présence Africaine.

(Keme Birama)

pp. 63–68

Les griots appellent cette chanson « Keme Birama Faasa ». En vérité, il n'en est rien...

Keme Birama est le jeune frère de l'Almamy Samory Touré. Aussi le griot qui a composé cette chanson devait-il partir du faasa de son aîné qui, dans la lignée des Touré, avait la préséance sur ses cadets. il devait donc faire un « mabalma ».

Et Samory Touré n'a pas été dupe. Les traditionalistes racontent qu'après avoir écouté le « Keme Birama Faasa », il a dit avec ironie : « Aujourd'hui, les quriots on mis les pattes de derrière avant les pattes de devant.» Un sage a répondu en ces termes : « Keme Birama est une étoile, et toi la lune ; et si Keme Birama se mettrait-il à briller comme le soleil que tu serais le brouillard. »

Aujourd'hui, le « Keme Birama Faasa » est considéré comme une des variantes du faasa de Samory Touré.

Ne l'appelez pas Sory ;

Il a nom Sory

Qui-dé-brouil-le-tout.

Ne l'appelez pas Sory ;

Il a nom Sory

Qui-dé-brouil-le-tout.

Rien n'échoue par la faute de Sory ;

Sory le frère de l'Almami

Et s'il arrivait à Sory de faillir,

Sory n'est-il pas le frère de l'Almami ?

[Ne l'appellez pas Sory... 2x]

Aux grandes noces de Kankan,

Aux grandes noces de Gankuna

Sory Birama avait trois grandes épousées,

Yoro, et Morijama Sere et Jugrufa.

[Ne l'appellez pas Sory... 2x]

La guerre est partout,

La guerre est de toute part ;

C'est la guerre sainte,

Et c'en est assez de la guerre.

Mori a combattu les blancs ;

Lanfia aussi.

Mais c'est pour Keme Birama

Que jouent ces deux tam-tams

Ces balafons et ces « jabara ».

Pourtant Mori a combattu les blancs,

Lanfia aussi

Et c'est pour Keme Birama

Que jouent ces deux tam-tams,

Ces balafons et ces « jabara ».

[Ne l'appellez pas Sory... 2x]

L'étoile annonciatrice brille

Pour le fils de Sogona,

Sogona de la famille des Camara.

Bien qu'il soit chaque matin

Le premier à s'éveiller,

La chance toujours devance

Le fils de Sogona.

[Ne l'appellez pas Sory... 2x]

C'est à Sory que je m'adress,

Sory, fils de Makeme.

Oui, c'est bien à Sory que je m'adresse.

A Bissandougou, il y eut

Une bataille sans merci

Griotes et griots, écoutez !

Tous les jours ne se ressemblent pas ;

Mais le fils de Makeme

Est l'auteur de maints exploits.

Lanfia Touré a engendré

Un homme pour de vrai.

Il y eut à Bissandougou

Une bataille sans merci.

Et que dire de celle de Sikasso ?

Célébrons, griotes et griots,

Le fils de Makeme qui a capturé

Sori-de-Bis-san-dou-gou en un seul jour.

Il y eut à Bissandougou

Une bataille sans merci.

Et que dire de celle de Soto ?

Des hommes tombèrent troués de balles.

Oui, le fils de Makeme

Est l'auteur de bien des exploits !

La guerre est partout,

La guerre est de toute part.

C'est la guerre sainte,

Et c'en est assez de la guerre.

[Ne l'appellez pas Sory... 2x]

Aux grandes noces de Kankan,

Aux grandes noces de Gankuna

Sory Birama avait trois grandes épousées,

Yoro, et Morijama Sere et Jugrufa.

[Ne l'appellez pas Sory... 2x]

Ministère de l’information du Mali. 1971. Première anthologie de la musique malienne: 1. Le Mali des steppes et des savannes: Les Mandingues. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2501.

(Keme Birama)

Kémè Birama (Fabou is his real name) is the younger brother of the Almamy Samory Touré, the epic poem about whom had the steppe and the savanna as its background. Only at the decline of his life did he go towards the forest. Compared to Napoleon for his military genius, he is the author of the sequel to the epic poem of Sunjata whom he admired so much. This great man of resistance and man of God, the emir of Ouassoulou, was banished to Gabon where he died in 1900, whereas his brother Kémè Birama, great warrior and commander of all his armies, died before Sikasso, where Tiéba was reigning, in 1887. Kémè Birama can only be sung with reference to his elder brother, and that for a traditional reason (primogeniture). And our Guinean brothers are right to make this song a variant of the praises of the emir of Ouassoulou:

The quiver (the army)

Is fixed to the picket (Kémè Birama)

And the picket adheres to the wall (Almamy Samory Touré)

But everybody agrees

In saying that Kémè Birama

Enjoys a great renown.

In the great battle of Kankan

And in that of Gankuna

Kémè Birama had

Yoro (his horse)

Manin Kaba Sere (his darling)

And Jugufa (his sword).

Ministère de l’information du Mali. 1971. Première anthologie de la musique malienne: 4. L'Ensemble Instrumental du Mali. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2504.

(Keme Birama)

Tradition reports that, after great victories over the colonizer, the whole army used to sing this song praising Kémè Birama to the skies; Kémè Birama, the brother of Almamy Samory Touré and general in command of all his armies.

Play, balafons,

Tom-toms and tambourines.

But play softly,

For I am going to speak of Kémè Birama.

Griots (poets) of Mandé, I can sing

But I do not sing of an insignificant man,

I am going to sing of Kémè Birama,

The brother of the Almamy Samory Touré,

Descendant of the Mandiou Touré

In the pure lineage of the Mandé Mori...

Charters, Samuel, prod. 1975a. African Journey: A Search for the Roots of the Blues. Vanguard, SRV 73014/5.

(Almami Samari Touray)

This song is of considerable importance, and deals with the background of the Guinea leader Almami Samari Touray, who fought a long, bitter war with the Europeans in the 19th Century, and was the grandfather of the present president of Guinea, Seko Toure.

This is in praise of the great man

Who is the subject of this song, the great warrior Alamami.

(Praise Melody)

You are loved by all people,

so be happy on earth, for all of us will die.

We're going to tell now what you have done

since your childhood.

May your soul rest in peace, your name will never be forgotten.

Now we begin to talk about Almami Samori Touray.

Almami Samori was born at Sanangkoro

in the Konoya area. He was a Mandingo,

but his mother was a Kissala.

(Praise melody)

You are loved by all people,

so you should be happy,

your life is not lived with unimportant people.

You, Fula, you are a great man whose words never fail.

You come from a good family, of the family of Musa Molo,

Who come from Yero Ege and Yero Yero Ege,

from the Dekori and Dansa.

You are a hero of the family of Musa Molo.

(instrumental refrain)

Almami Samori was a warrior, a warrior whose skills

came from no-one but himself. His father was not a king,

his mother was not a queen, but she was from a royal family,

from the family of Sohna Makau Camara.

His father was called Langfiya Touray.

Langfiya Touray decided that he would be a great trader,

but those of his family, all with the same father,

Allah made them richer than Langfiya Touray.

They were richer, and in time he became too poor

even to afford a wife.

So he went on a journey, and when he was gone the relatives

called a meeting behind his back and they asked each other,

"Why has Langfiya gone on a journey? Let us get together

and take his family." And they divided up the possessions

in Langfiya's compound because they did not want him with them

Some of them said, "Langfiya will never come again, so

we can take his family and divide it among us."

Langfiya had gone to Jah. After he left Jah he went to Kulusa

and from Kulusa he went to Sigiring. From Sigiring he went to

Mamu, and from Mamu went to Kankalabeh. He found a

marabout there named Almami Kula. When he got to Almami

Kula then Almami Kula asked him, "Young man, where are you

going?" And he said, I am called Langfiya Touray. I was born

in Solong Kora in the Koniya area,

but i don't want to stay in this place where I was born.

Then the marabout asked him "Why?"

(humming)

"Because I pray to Allah, and it isn't a place where

this is done.

In this place where I was born anywhere I pray people

tell me to gather up the place and take it away with me

and they beat me."

(long instrumental refrain). . . . . .

Kaba, Lansiné. 1976. "The Cultural Revolution, Artistic Creativity, and Freedom of Expression in Guinea." Journal of Modern African Studies 14 (2): 201–18.

(Regard sur le passé)

Art and history have thus been reinterpreted to conform to Touré's views and examples, and to ennoble his origin, as songs and writings stress that he belongs to the lineage of Samori Touré, a hero of African resistance. For example, Regard sur le passé—an epic in honour of African resistance which secured a gold medal for the Guinean delegation to the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival held in Algiers, and a best selling record in French-speaking West Africa during the early 1970s—praises Samori's virtues and deeds, and ends as follows:

Ils ne sont pas morts, ces heros, et ils ne mourront pas. Après eux, d'audacieux pionniers reprirent la lutte de libération nationale qui, finalement, triompha sous la direction d'Ahmed Sékou Touré, petit-fils de ce même Samori. Le 29 Septembre 1958, la Révolution triompha, nous vengeant définitivement de cet autre 29 Septembre 1898, date de l'arrestation de l'Empereur du Wassoulou, l'Almamy Samori Touré.1

1 Bembeyya [sic] Jazz National, Regard sur le passé, side B, S.L.P. 10. The concluding songs in Mandinka compare Sekou Touré to Sundiata of the Mali Empire, Alfa Yahya Diallo of Labe in Futa Jallon who was deported by the French, and to other God-entrusted leaders. Thus in the phraseology of Terence Ranger and Michael Crowder, one of the origins of modern nationalism lay in 'primary resistance'; and Touré is unique because he is both a political and consanguineous heir to Samori.

Knight, Roderic. 1982a. "Manding/Fula Relations as Reflected in the Manding Song Repertoire." African Music 6 (2): 37–47.

(Sori)

p. 39

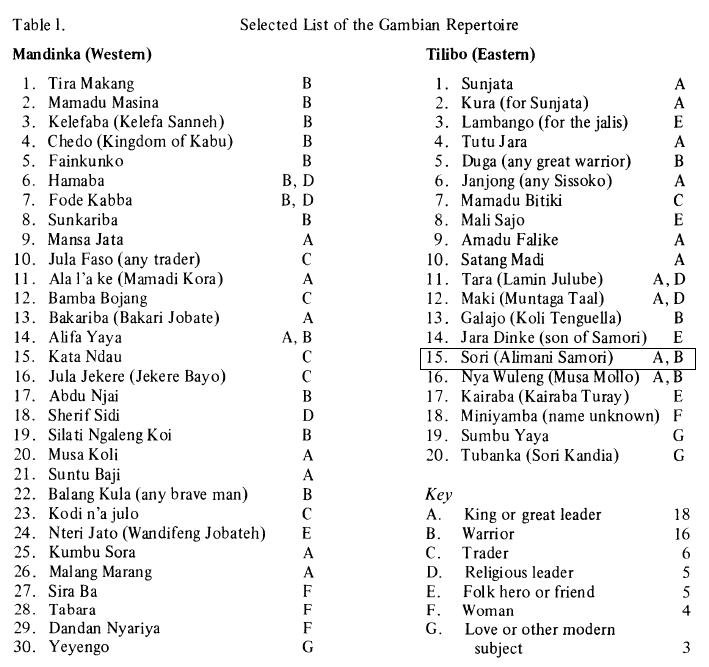

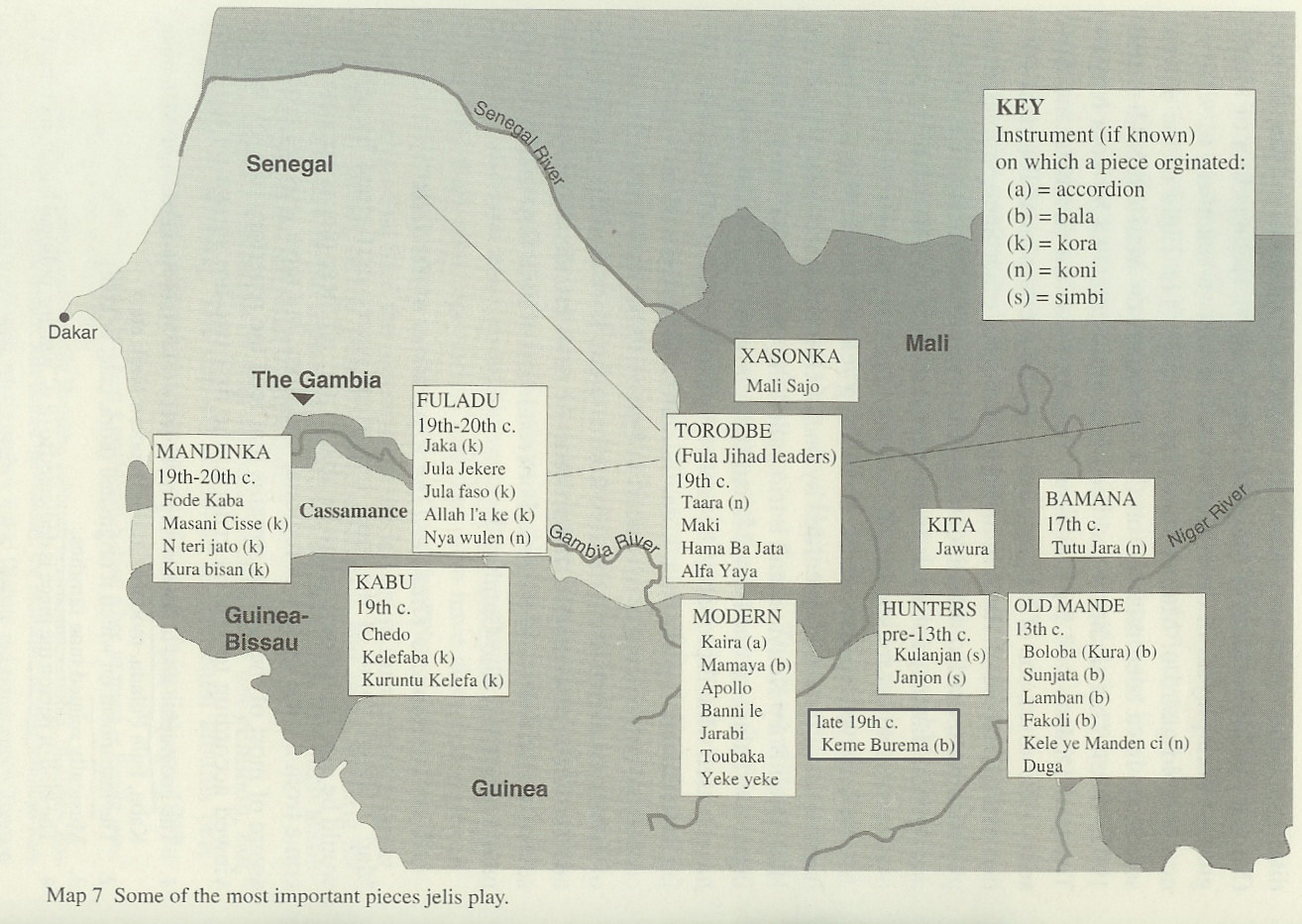

Table One . . . includes the best known, most often heard, or otherwise significant songs in the [Gambian] repertoire. In each column the top few songs are the oldest, and the bottom few are the youngest. The majority in each case fall somewhere in between (often in the nineteenth century), but no chronological ordering beyond this is intended, since it is often not possible to date a song exactly. Most of the songs bear the name of their owner as the title. Where they do not, his name is shown in parentheses next to the title. The letter code at the right represents the person's "claim to fame" or calling in life, as shown in the bottom of the list.

p. 40

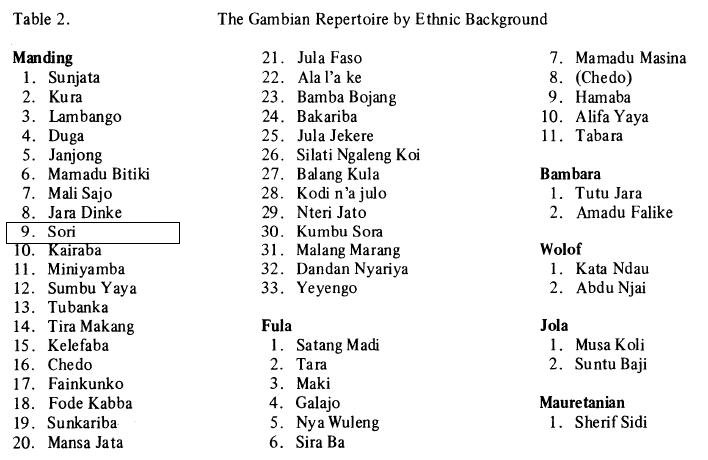

Table Two shows the same fifty songs again, grouped this time by the ethnic background of the people commemorated.

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Sori)

pp. 71–76

Donkilo (on teaching tape)

| I ye eh mbara jonyaa; Faama jong mang i lambango long | Faama, no man knows his end |

Related information

Alimami Samori Touray (b. 1840) was the last mansa and great warrior of the Mandinka Empire of Ouassoulou (Wasulu), now in the Republic of Guinea. He built the empire through war and treaties, establishing his capital at Bissandougou in 1879. Together with his brother, Keme Buraima, he fought the French colonists and opposing African forces for twenty-eight years. Keme Buraima was the general of his brother's armies but was killed during a battle. Alimami Samori's progress as a warrior was so great that the jalis dedicated "Sori" to him, stressing his bravery by saying "If someone is fighting, Tourary will be fighting; even if no one is fighting, Touray will still fight." He was captured by the French in 1898 and held as a political prisoner until his death in 1900.

His grandson, Sekou Toure, was the president of The Republic of Guinea from its independence in 1958 until his death in 1984.

pp. 146–59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Sori (Alimamy Samory) |

| Translation: | Name |

| Dedication: | Alimami Samori Touray |

| Notes: | a.k.a. Alimami Samory |

| Calling in Life: | King or Leader, Warrior |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | M (19th & 20th c. up to WWII) |

| Sources: | 1, 3 (Jessup & Sanyang, R. Knight 1973) |

| Title | Keme Buraima |

| Translation: | "Hundred" Buraima |

| Dedication: | Buraima Touray |

| Notes: | brother of Alimami Samori Touray |

| Calling in Life: | Warrior |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | M (19th & 20th c. up to WWII) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

Jatta, Sidia. 1985. "Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia." In Repercussions: A Celebration of African-American Music, ed. Geoffrey Haydon and Dennis Marks, 14–29.

(Saamoori)

p. 23

Not all the pieces in the repertoire bear personal names as their titles, but most of them are named after the personalities for whom they were originally composed. Some examples of these are: FodeKabaa, Kelefaa, Saane, Saamoori, Alfaa Yaayaa, Mammadu Maasina, Satan Madi, Sirifu Siidi and Jula Jekere, all of which bear the names of historic figures.

Sadji, Abdoulaye. 1985. Ce que dit la musiqe Africaine.... Paris: Présence Africaine.

(Samory)

pp. 75–83

La première chose que le diali me dit sur Samory fut que ce dernier ne pouvait pas avoir d'enfants. Chose singulière, quand on considère que cet empereur entretenait cependant tout un harem... Ce détail me fit penser à l'autre empereur des Toubabs* qui avait répudié sa femme parce qu'elle ne lui donnait pas d'enfants.

Le diali accorda son instrument et se mit à jouer un air, composé en l'honneur de Samory par ses deux ou trois cents dialis.

Musique étrange, pleine de la nostalgie du passé.

La musique africaine a ceci de particulier qu'elle ne sert pas d'introduction à la narration des faits ; elle ne la suit pas non plus, elle l'accompagne, l'enveloppe et en marque les divers épisodes. Et l'imagination et la sensibilité, exaltées par cette musique, croient voir ou sentir une unité, là où il n'y a que des moments de la vie d'un héros.

Mais une chose au moins est certaine, c'est qu'en écoutant les coras, on a l'impression que le passé vit et se meut...

Au cours d'une guerre dans le Baoulé, Samory captura une femme et son enfant, un garçon.

Or Samory tua la mère et voulut conserver l'enfant pour l'adopter. Il lui chercha une nourrice et lui donna le nom de Niouling-Karamoko (l'homme aux yeux rouges, le brave des braves). Il l'initia très tôt aux choses de la guerre, si bien que Niouling, tout enfant, sentait un besoin impérieux naître en lui: celui d'aller à l'aventure, de guerroyer, de prendre des villes et des esclaves.

Un certain jour même, Niouling dit à Samory :

— Père, repose-toi. Je vais moi-même prendre les villes où tu veux entrer.

Mais le colonel blanc vint prendre Niouling-Karamoko et l'emmena en France. Là on le fit monter sur un édifice très élevé—la tour Eiffel—du haut duquel il vit toute la puissance des Toubabs. L'enfant de Samory revint parmi les Noirs, la tête pleine de visions de France.

Il fit part de ses impressions à Samory :

— Père, lui dit-il, tu laisseras tranquille les Oreilles Rouges. Leur puissance est grande et tu ne pourras jamais les battre et prendre leurs villes.

Samory s'indigna devant ce fils si crédule et si peu audacieux.

— Meurs, lui dit-il, enfant de sang mêlé. Tu n'es pas le fils qui conservera mon empire.

Et il mit fin aux jours de Niouling-Karamoko.

Samory défendit à ses griots de chanter la gloire de celui qui avait vu de ses propres yeux la puissance des Blancs.

Après cela, Samory eut un propre fils, auquel il donna le nom de Sananké-Mory. Un jour, ce fils commit une mauvaise action... Comme Samory le châtiait trop fort, l'enfant s'enfuit et alla se réfugier auprès de son grandpère, l'Anfia-Touré, à qui il conta sa mésaventure.

Samory étant assis près de son épouse favorite Snan, celle-ci lui demanda :

— Est-il vrai que tu as chassé ton fils auprès de ton père ?

Et Samory dit :

— Oui.

Alors Snan manifesta sur place son désir de connaître la position d'un enfant dans le ventre de sa mère.

— Baky ! Baky ! répondit Samory. Tu vas voir. Il fit venir une femme enceinte, l'éventra et s'adressant à Snan :

— Baky ! ma chère épouse, tu vois maintenant.

« Baky... Baky ! » était l'expression par laquelle Samory traduisait l'opinion qu'il avait et de lui-même et de sa puissance.

Mais Snan voulut savoir encore comment l'homme se débat dans le feu. Samory fit venir deux mille enfants et chargea deux cents hommes d'aller ramasser du bois dans la forêt. Un immense feu fut allumé dans lequel on jeta les deux mille enfants.

— Baky ! dit Samory à Snan. Ma chère épouse, tu vois maintenant.

On tournait et retournait les deux mille enfants dans le feu, avec de longs bâtons encore verts. Et les deux mille enfants sautaient et éclataient comme des graines d'arachide qu'on grille.

— Baky ! dit encore Samory. Ma chère épouse, tu viens de voir le secret d'une femme enceinte, et devant toi, deux mille enfants se trémoussent dans le feu. Baky..., je crois que tu es satisfaite. Maintenant, c'est à ton tour de danser au milieu des flammes.

Et sans hésiter, il fit jeter Snan, son épouse favorite, dans la fournaise .

« Baky... Bang té ou yare » (le mensonge ne saurait durer). Samory n'était pas homme de sentiment. Il ne pouvait résister à ses pires instincts. C'est pourquoi il multipliait les canages et aimait à faire souffrir et verser du sang.

Il voulut attaquer Kong, ville sainte, habitée par des « Vali-You ». Mais les « Vali-You » invoquèrent Dieu qui jeta les ténèbres sur la ville. Samory renonça momentanément à s'emparer de Kong.

— Baky... Bang té ou yare » (le mensonge ne saurait durer).

Bientôt Samory attaqua vraiment Kong, la brûla, fit de nombreuses victimes et revint à Sanan-Koroba. Baky !...

Il se tourna alors contre les Français, s'empara de leurs canons, prit beaucoup d'hommes, en tua certains, quant aux autres, il les circoncit.

Baky !... Il prit le commandant B... et le balafra.

« Baky... Bang té ou yare. »

Il attaqua les Timiné et fut battu par leur roi Mazamragne, surnommé « l'Incomparable ». Samory lui fit don de beaucoup d'or pour prix de sa liberté. Cette défaite ne fut connue de personne.

« Baky... Bang té ou yare. »

Samory vaincu par Mazamragne l'Incomparable, voilà la vérité. Tout le reste est mensonge.g

Samory revint chez lui. Sa défaite demeura secrète, car on redoutait sa colère.

« Baky... Bang té ou yare. »

Les jours de fête, il faisait organiser un grand bra. Toutes les filles étaient présentes...

Un vendredi après-midi, Samory quitta le bra et trouva quatre cents dialis qui entouraient son fils en chantant ses louanges. Il salua. Mais comme Sananké-Mory, son fils, mit un moment pour répondre, Samory trembla de colère et le sermonna en disant :

— Ah ! tu es gonflé d'orgueil parce que les griots t'entourent ?

« Baky... Bang té ou yare. »

Et il mit les quatre cents griots à mort.

Malgré la défense formelle de Samory, NioulingKaramoko a sa musique que tous les dialis d'hier et d'aujourd'hui connaissent. Sananké-Mory a aussi sa musique. Mais celle de l'Almamy, leur père, est de toutes la plus mâle.

Une autre fois, il prit une de ses femmes en flagrant délit d'adultère avec un esclave.

« Baky... Bang té ou yare. »

Il tua l'esclave, fit déshabiller la femme et l'exposa dans la cour, sexe en l'air. Alors les autres femmes, ses rivales, qui pilaient le mil pour le roi et toute sa suite, venaient jeter le son sur le ventre de la coupable.

Il quitta son territoire pour aller se battre à MohoDomo. Les hommes de cette contrée étaient des chiens et les femmes avaient forme humaine.

« Baky... Bang té ou yare. »

Il voulut les attaquer, mais fut accueilli de toutes parts par des aboiements ridicules. Il renonça à se battre contre un peuple de chiens.it.

Baky !...

Il alla trouver le roi Massa-Kone, souverain du MohoDomo, et voulut lui parler, mais l'autre aboyait. Samory, dégoûté, quitta la contrée.

Baky !...

Il alla à Sankaran où était né son griot MorfiniangDiébaté. A Sankaran, il fit de nombreuses victimes et ravagea la contrée. Puis il revint dans son pays et quelques jours après, il était capturé par les Français.

Baky !...

Or, Morfiniang-Diébaté, le griot de Samory, est le grand-père du diali Bakary, qui raconte cette histoire, parce qu'il la tient de son père, qui la tenait de Morfiniang-Diébaté lui-même, compagnon fidèle du grand guerrier noir.

« Baky... Bang té ou yare. »

Samory disait que le mensonge ne saurait durer. Faire des prières et des génuflexions, dire son chapelet tout le long du jour, tout cela : mensonge... La vérité, croyaitil, consiste à égorger les enfants, à tuer les vieillards et à dévoiler aux yeux du monde le secret d'une femme enceinte que la nature cache si jalousement.

Sur la place des réjouissances, il levait la main et le bra cessait. Alors il s'adressait à tout le monde en disant :

— Sima ya ni ndiate ken déa... Que Dieu donne longue vie et bonne santé à ceux qui regardent le bra ou qui dansent dans le bra, et au griot qui joue. Je donne cent esclaves au griot. Maintenant, je veux que le bra cesse.

Et tous quittaient la place des réjouissances.

Mais cette histoire des Français, qui l'ont poursuivi, cerné et attaqué en lui disant: « Ille Samory », tout cela est mensonge.

« Baky... Bang té ou yare ».

Il avait une culotte qu'il n'enlevait jamais parce qu'elle était la sauvegarde de son empire et de sa puissance. Un jour, sa femme lui demanda d'enlever sa culotte. Samory obéit : Le lendemain tous ses gris-gris étaient perdus.

Il appela ses esclaves, mais aucun ne se présenta. Il voulut s'entourer de ses sujets, mais tous se détournèrent de lui. Il sentit que sa fin était proche. Quelques jours après, il était capturé...

« Baky... Bang té ou yare. » Mais l'homme ne dure pas plus que le mensonge. L'homme est un mensonge visible. Il n'y a qu'une seule chose qui dure : les exploits des héros et la musique des dialis qui les fait revivre et connaître aux hommes.

*Toubabs : Blancs.

Kouyate, (El Hadj) Djeli Sory. 1992. Guinée: Anthologie du balafon mandingue. Vol 2. Buda, 92534-2.

(Kémé Bouréma)

Dedicated to Kémé Bouréma, an important war chief of the Almamy Samory Touré, reputed for his braveness and high strategic sense.

Diabate, Sidiki. 1987. Sidiki Diabate and Ensemble: Ba togoma. Rogue, FMS/NSA 001.

(Sori)

One of the great Manding heroes was Samory Touré, who controlled a large part of Guinea and Mali in the late 19th Century, but was captured by the French and died in exile in 1900. This song is dedicated to his younger brother, Ibrahima 'Sori' Touré, a brilliant general and beloved patron of musicians. The bala xylophone plays the vocal refrain.

Kaba, Mamadi. 1995. Anthologie de chants mandingues (Côte d'Ivoire, Guinée, Mali). Paris: Harmattan.

(Keme Brema1)

p. 105

L'autruche est descendue

Sur la cité de Kankan !

L'autruche, ce n'est pas Sory !

L'autruche, c'est Kémé Bréma,

Le Seigneur aux trois épouses.

Sa première épouse est

Son vaillant cheval "Djoro".

Sa seconde épouse,

C'est "Mariama Séré".

Et en fin, sa troisième épouse,

C'est son sabre "Mort à l'ennemi".

1 Kémé Bréma, le demi-frère de Samory était le commandant en chef des armées decelui-ci. C'est Kémé Bréma qui a pris la ville de Kankan après neuf mois de siège, de juillet 1880 à mars 1881. Kémé Bréma, c'est également le seigneur aux trois épouses qui sont : d'abord, son cheval, en suite sa femme préférée et en fin, son sabre dénommé "mort à l'ennemi". Kémé Bréma veut dire Bréma, fils de la femme Kémé.

On sait qu'au départ, l'armée de Samory et celle de Kankan s'étaient alliées sur la base de la solidarité islamique conclue à Tni Woulén en 1873 et confirmée à Kankan en 1875. Contrairement à ce principe, Samory voulut s'attaquer à ses anciens maîtres CISSE qui étaient musulmans et qui avaient réduit sa mère à l'esclavage. Mais Karamo Mory, chef de Kankan lui signifia son refus. Encouragé par Kémé Bréma, Samory attaqua Kankan qui tomba de famine après neuf mois de siège. Cette prise de Kankan fut considérée à l'époque comme l'une de ses plus grandes victoires. Aussi, Kankan devint la seconde capitale impériale de Samory pendant huit ans, de 1881 à 1889 à l'arrivée des troupes françaises.

Kouyate, M'Bady, and Diaryatou Kouyate. 1996. Guinée: Kora et chant du N'Gabu, Vol 2. Buda, 92648-2.

(Keme Bourama)

Dedicated to Keme Bourama, a great war leader from Almany Samory Touré, for his bravura and great military strategy.

Suso, Foday Musa, and Bill Laswell. 1997. Jali Kunda: Griots of West Africa and Beyond. Ellipsis Arts, CD3511.

(Sorrie / Keme Burama)

A praise song that originally honored Keme Burama—and later his brother, Sorrie—for their strength, kindness and fame. Keme Burama was the grandfather of the late Guinean President, Saikou Touray. This piece is popular in Guinea and thoroughout the Mandinka region.

Kouyaté, Sory Kandia. 1999. L'épopée du Mandingue. Mélodie, 38205-2. Re-issue of 1973, SLP 36, SLP 37 and "Toutou diarra" from SLP 38.

(Kémé-Bouréma)

Chanson de geste de Kémé-Bouréma Touré, frère cadet et général de l'Émir Almamy Samory Touré, empereur du Wassoulou. De son vivant, à lóccasion des parades militaires, les balafons accordaient cette musique à l'allure du cheval de Kémé Bouréma, le héros de plusieurs batailles des armées Samoriennes.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Keme Burema / Samory / Sori)

p. 81

Although Maninka and Wasulu hunter's pieces may praise some of the same heroes, such as Fakoli (Coulibaly 1985:60) or Samori Toure, the musical vehicles that carry them, such as harps and their tuning systems, are indicator of ethnic identity (siya).18

p. 148

p. 153

Keme Burema is named after the brother of Almami Samory Toure, the late nineteenth-century general and political leader who conquered much of upper Guinea, Wasulu in southern Mali, and Kong in northern Côte d'Ivoire. It is a praise vehicle for Toure that is very important in Guinea, in part because of his Guinean origins and also because Guinean president Sekou Toure has claimed a close family relationship with Samory Toure.85 Like Sunjata in Mali, Keme Burema has been recorded by modern orchestras; the most ambitious effort is the album-length Regard sur le passé of Bembeya Jazz (1970-disc).

85. According to Sidiki Diabate (1990-per:83–85) Tasilimanga Konte was one of Samory Toure's jalis. His younger brother Harengale Konte was a jali of Muntaga Tal (son of Umar Tal) Diabate’s pronounciation occasionally alternated between Konte and Kone.) L. Kaba (1990:53) has recounted an occasion where Sekou Toure was publicly presented as a nephew of Samory Toure's nephew. Perhaps resulting from this, Samory Toure's lineage in Kankan and Sanankoro in Upper Guinea then adopted Sekou Toure, whose father came from Mali.

p. 250

Older pieces from the jeli's repertory were rare on commercial recordings before the 1960s.13

13. The few tradtional jeli pieces with guitar accompaniment recorded before independence include Mali Sajo (Sory Kandia Kouyate) 1956?-disc), and Sakodugu and Samory, on a Phillips 45 rpm from about 1959 featuring Kavine Kouyate, Kelema Doman, and Odia Conde (Nourrit and Pruitt 1978, 1:48–49)According to Sidiki Diabate (1990-per:83–85) Tasilimanga Konte was one of Samory Toure's jalis. His younger brother Harengale Konte was a jali of Muntaga Tal (son of Umar Tal) Diabate's pronounciation occasionally.

p. 263

The 1968 Bembeya Jazz album-length epic Regard sur le passé, based on the jeli piece Keme Burema, featured Djeli Sory Kouyate on bala, a sure sign of shedding of Cuban influences in favor of local music.

p. 285

In Guinea, Sunjata, Tutu Jara (associated with the Bamana Segu Kingdom), and Lamban hardly figure in the modern orchestra repertories. One of the most important pieces is Keme Burema, which is used to tell the story of Almami Samory Toure, a central figure in late nineteenth-century Guinea. The album-length version by Bembeya Jazz, titled Regard sur le passé (1970-disc), is a classic.

pp. 295–96

(See Charry, 2000.) (Bala and guitar transcriptions.)

pp. 398–401 (Appendix C: Recordings of Traditional and Modern Pieces in Mande Repertories)

Bala: Keme Burema

Unidentified (Sily, Guinea Compilations 1962a; Guinea Compilations 1962b)

Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine

Bembeya Jazz (Regard sur le passé, 1970)

Nantenedie Kamissoko (Ministry of Information of Mali, 1971, vols. 1 and 4)

Sory Kandia Kouyate ([1973] 1990)

The Ivorys (Yanburi Pa Koura [1984] 1987)

Baaba Maal (Dogota, 1991)

Dogomani Dagnon (1993)

Djimo Kouyate (1992a)

Baba Djan Kaba (Djanfa, 1992)

Mansour Seck (Quinze Ans, 1994)

Fula Flute. 2002. Fula Flute. Blue Monster.

(Keme Bourema)

King Samory Toure didn't like his country being invaded by the French. In the 19th century, he fought them all the way, fiercely. They tried to capture him but he kept evading them. One day they finally succeeded. He died when they dropped him into a vat of boiling tar.

(Keme Burema)

A 19th-century historical song about how the French turned the son of Samori Touré against him. Some of the original lyrics are sung through the flute.

Diabate, Madou Sidiki. 2006. Traditional Kora Music from Mali. System Krush/Ascap, CD006.

(Keme Burama)

Keme Burama is the brother of Almamy Samory Toure, and was a general in his army, essential to the success and expansion of the Wasulun Empire of southern Mali, and a fierce adversary of the colonial French. Dedicated to Keme Burama by Morifinjan Diabate, Djeli of Samory Toure, during the one-year siege of Kenedugu, in the Sikasso Kingdom.

Williams, Joe Luther. 2006. "Transmitting the Balafon in Mande Culture: Performing Africa at Home and Abroad." Ph.D. diss., University of Maryland.

(Keme Burema)

p. 118

. . . Keme Burema, an extremely popular piece in Guinea because it is associated with the country's first post-colonial president, Ahmed Sekou Touré. The piece was originally named after the courageous brother of Almami Samory Touré, a nineteenth-century general who valiantly fought against the French in their attempts to colonize the parts of northern Guinea and southern Mali under his control, whom Sekou Touré claimed as an ancestor.

Diaby, Mohamed. 2007. Ala Na Na. Mohamed Diaby.

(Kème Bourama)

Dedicated to Kème Bourama, a great spiritualist an [sic] elegant and brave man of the village of the griots.

see also:

Jansen, Jan. 2002. "A Critical Note on 'The Epic of Samori Toure.'" History in Africa 29: 219–29.

Knight, Roderic, dir. 2010. Music of West Africa: The Mandinka and their Neighbors. Lyrichord Discs, LYRDV-2005.

Person, Yves. 1963. "Les ancêtres de Samori." Cahiers d'Études Africaines 4 (13): 125-56.

Peterson, Brian J. 2008. "History, Memory and the Legacy of Samori in Southern Mali." Journal of African History 49 (2): 261-79.

Rouget, Gilbert, prod. 1999. Guinée: Musique des Malinké. Le Chant du Monde/Harmonia Mundi, CNR 2741112. Reissue of all Guinean material from 1954 and 1972 with expanded notes.