komo (komodenw)

Knight, Roderic. 1974. Review of Musique malinké: Guinée by G. Rouget; Musique d'Afrique occidentale: Musique malinké, musique baoulé by G. Rouget. Ethnomusicology 18 (2): 337-339.

(Chant pour le Masque Oiseau [Kòma])

p. 338

The village music includes two examples of drumming, one without singing, the other a new item with a female chorus singing about the now rare koma mask dance.

Zahan, Dominique. 1974. The Bambara. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill.

(Komo)

p. 17-18

When the children leave the n'domo brotherhood (where they spend five years: one year for each initiatory "class", the oldest pupils being replaced by newcomers), they are circumcised, which means that they are now relieved of their androgynous nature, by the removal of their female element (represented by the foreskin) and directed towards the search for their social partner (woman). It is now that another initiatory brotherhood takes charge of them: the komo (Pl. XXIII-XXIV).

A Bambara cannot speak of the komo without a feeling of awe, or even of terror. That is why he generally speaks of it in a low voice, when he cannot be overheard by his fellow villagers. The fear inspired by the komo is caused by its association with human knowledge.

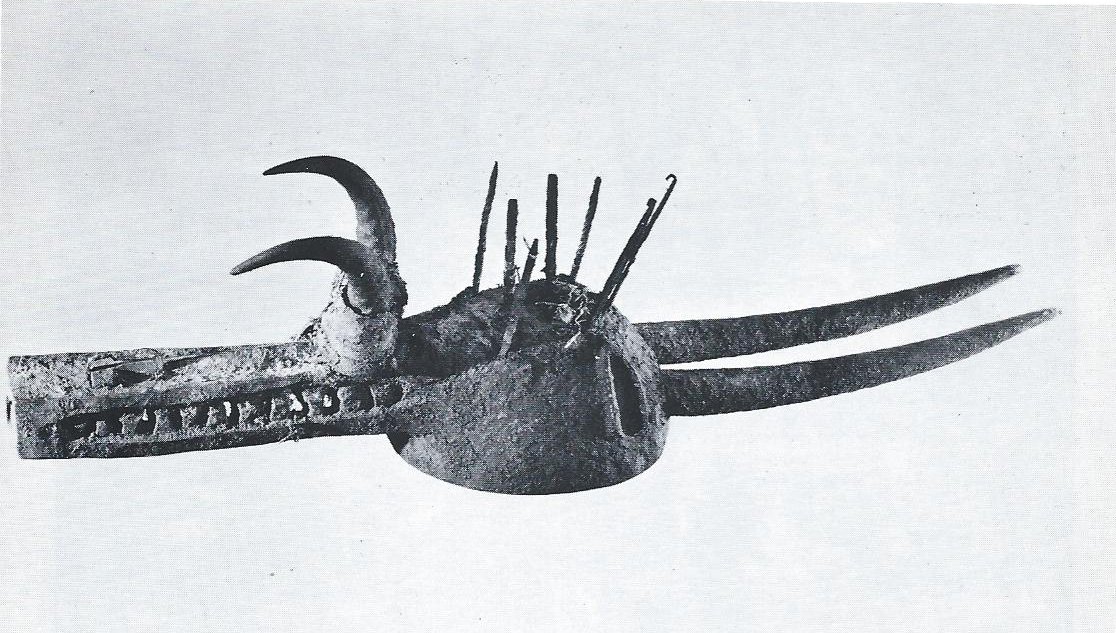

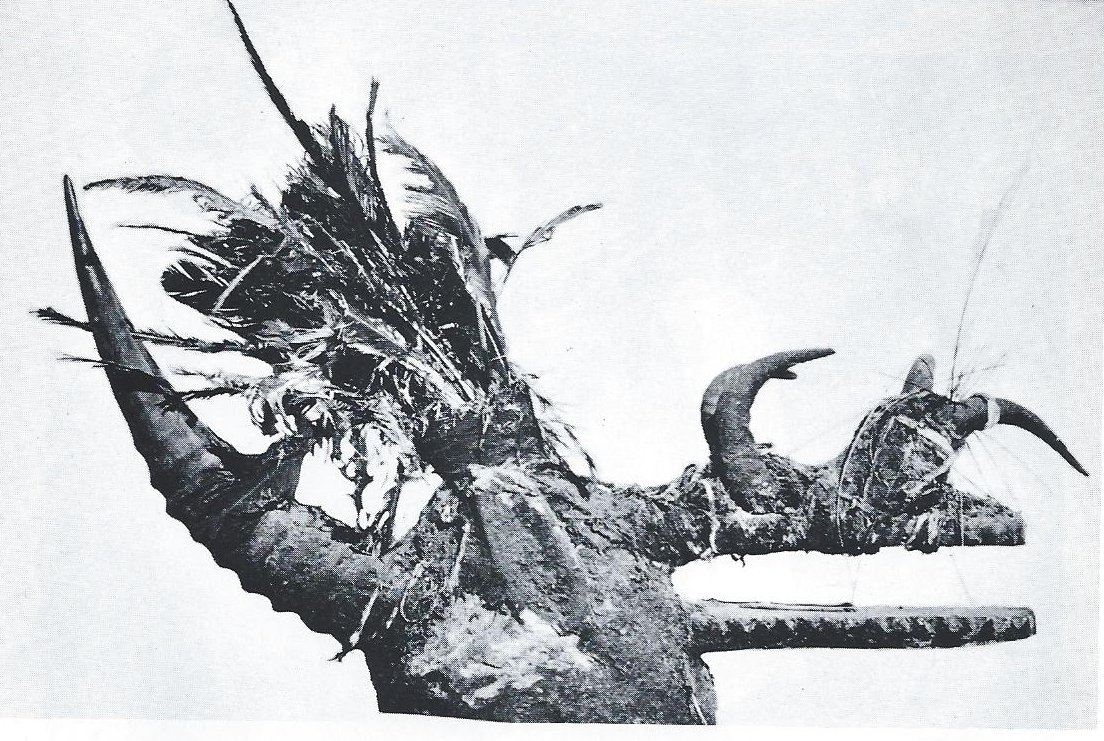

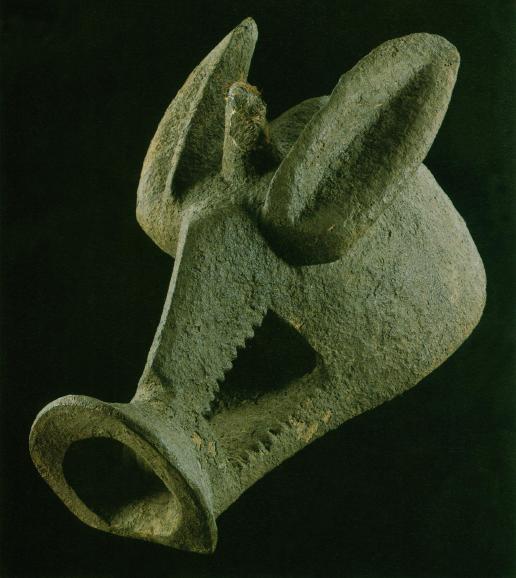

Komo mask. Two details should be noticed on the komo masks, the powerful jaw which represents the hyena (symbol of knowledge, capable of crunching even the hardest bones) and the horns in a position to attack, which again refers to knowledge, said to attack those who take it too lightly.

Provenance: Mali Republic. - Dimensions: I m. x 0.30 m. — Material : wood of kapok tree. — Collection: D. Zahan — Photographed by Musée de l'Homme.

Komo mask.

Provenance: Mali Republic. — Dimensions: 1 m. x 0.25 m. — Material: wood of kapok tree. — Private Collection. — Photographed by Musee de l'Homme.

At Douga, Mali Republic. Dance of komo mask.

Photographed by D. Zahan.

At Douga, Mali Republic. Dance of komo mask.

Photographed by D. Zahan.

All that concerns this subject smacks of a kind of defiance, an attitude of provocation which knowledge assumes towards all who seek it. Through the komo knowledge reveals itself, sometimes as seductive and pleasing, sometimes as rough and repellent. It is nevertheless always ready to confound the hypocrite and the liar, to unmask the vain and to silence the proud. And as no mortal, not even the wisest, feels totally immune to these sentiments, knowledge is for everyone a source of apprehension.

Knowledge, as explained by this initiatory society, may be considered under four aspects, through the four fundamental komo each of which expresses it from a different point of view. This is what the Bambaras mean when they talk about the komo "mothers". Everyone of these "mothers" has a certain number of secondary 'komo' called "children". These complete and expand the idea expressed by their respective "mothers". The "komo" all together thus form an immense institution which, at first sight, seems to lack a properly so called hierarchy. The only obvious hierarchy is that which orders the relations between a "mother" and her children, or between a "child" and the swarms to which it has given birth.

The first komo "mother" (first in the order of the revelation of knowledge) bears the name of "se" (foot) and represents the beginning of knowledge. The foot is in fact the symbol of a beginning, an advance, of success and power. As the foot enables a man to walk, to move forward, and to make progress in space, so the "se" teaches all that concerns the access to knowledge and the progress made in its pursuit. The second komo "mother" is called sutoro that is, the "corpse fig-tree". The toro (ficus graphalocarpa A. Rich) symbolises germination proliferation and re-birth. The name sutoro alludes to the funerary custom, observed by the Bambara, of burying a branch of this tree with the dead, to represent re-birth. This "mother" represents enlightenment, and teaching by demonstration, for since the principles of a truth (like the corpse resting in the ground) are lost in obscurity, to prove an assertion is like bringing these principles back to life.

The kama "mother" called tamla (flame) indicates the numinous character of knowledge. It signifies also the illumination and excitement which the mind feels at a certain moment during the acquisition of knowledge. Finally, the "mother" called karangara "to bring unhappiness", suggests the idea of suffering caused by knowledge, for this komo sees knowledge as a torment for those who seek it. In fact, the wise man who wishes to reach the summit of knowledge in order to enjoy it in tranquillity, deceives himself greatly, for knowledge is boundless, and the search for it is endless. The scholar might be tempted to believe that he could penetrate beyond knowledge, this is a vain hope: nothing can go beyond it. The acquisition of knowledge and man's attitude to it constitute for the Bambaras one of the most serious problems in the initiatory stage, for it is at this level that the Society judges its young members. Its judgment takes into consideration first of all their power to comprehend things in thought, as well as their capacity to guard the secret of the truths revealed to them.

(Komo)

p. 215-6

Au Manding, le grand masque religieux est le Komo ; quand il paraît, tous les non-initiés doivent se cacher. C'est la société secrête du Komo qui édicte les interdits, en somme légifêre pour la communauté ; c'est une société três restreinte, il faut avoir conquis fêre pour la communauté ; c'est une société très restreinte, il faut avoir conquis plusieurs grades pour prétendre entrer dans la société, entre autres avoir été agréé dans la confrérie des chasseurs ou avoir acquis une grande réputation dans la connaissance des « secrets de la Brousse » . Le Komo est un masque de lion ou d'animal fauleux barbouillé de jus de cola et de sang de poulet. C'est le plus secret des masques mandingues.

Camara, Ladji. n.d. Africa, New York. Recorded 1975. Lyrichord, LYRCD 7345.

(Koma)

Koma means fetish and this is a woman's [sic] secret society. This dance takes place once a year only. The women dance nude covering their faces with masks, which are made to resemble them. No men are allowed to witness this dance, however the men carve these masks for the women ornamented with beads and raffia. The dance is performed for a full day during the month of January. This song is to the God Koma, a woman's [sic] fetish that oversees women's affairs.

Keita, Mamady. 1989. Wassolon. Fonti Musicali, FMD 581159.

(Komodenu)

Koma ou Komo signifie fétiche, et Komodenu désigne les enfants du fétiche ou les apprentis du fétiche. Quand le Komo sort, les femmes et les enfants—qui ne peuvent pas le voir—restent dans les maisons.

| E Komodenu | Eh vous! les enfants du Komo |

| Sisi bora Tamaniko | Regardez la fumée qui vient de Tamaniko |

| Taa wulida komo so la | Le feu a pris dans la maison du Komo |

| Sisi bora Tamaniko | Regardez la fumée qui vient de Tamaniko |

Diabate, Karamba. 1996? Journey Into Rhythm: The Rhythms & Music of Guinea West Africa. 2 vols. Third Ear Productions.

(Komodon)

In the Malinke language, komo means crazy, and don means dance: "crazy dance." This rhythm is a masked dance and can only be seen by the initiated. It is also played to honor the insane and mentally ill.*

* Transcription mine.

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Komodemu)

p. 62

The song that accompanies the rhythm [Kotedjuga] is called Komodemu.

Polak, Rainer, prod. 1999. Jakite, Dunbia, Kuyate, and Samake: Bamakò Fòli: Jenbe Music from Bamako (Mali). Self-produced.

(Komo / Komofòli)

Komo is a secret society (French: société d'initiation). This and other regional religio-political institutions lost most of their power during the Fulbe's islamic jihad (second half of 19th century) and during the colonial and post-colonial periods. Yet Yamadu was very active in playing them in rural areas well into the 1970s. Several rhythms are performed for the komo ceremonies in one place, and they vary from region to region. The one played by Yamadu in Bamako is known in the area south of Bamako by both the Bamana and Maninka.

Rouget, Gilbert, prod. 1999. Guinée: Musique des Malinké. Le Chant du Monde/Harmonia Mundi, CNR 2741112. Reissue of all Guinean material from 1954 and 1972 with expanded notes.

(Chant pour le masque oiseau (kòma))

p. 47

Dans les années vingt de ce siècle, la religion traditionnelle était encore très vivante à Karala. Dans les années quarante, les propagateurs de l'Islam, prenant le dessus, parvinrent à faire brûler les « fétiches ». Les mystéres du kòma, société secrète à masques, pivot de la religion, furent exposés aux yeux des femmes et des non initiés. Depuis lors, les rites du kòma n'ont plus été célébrés dans ce village, devenu entièrement musulman. Lorsque le masque oiseau kòma (la grue couronnée), venu de brousse, dansait au village, accompagné de ses servants, seuls les initiés pouvaient le voir ; femmes, enfants et griots avaient interdiction absolue de sortir de la maison et de regarder. En certaines circonstances, cepandant, des chats pouvaient faire allusion au kòma, notamment pendant la fête réunissant hommes et femmes du village durant la veillée précédant la circoncision. C'est un chant de ce type qu'on entend ici. On y évoque le kòma du village voisin de Tyawa, qui a pour nom duwa su, « vautour mort ». La batterie est fournie par trois tambours à une peau du type de ceux qui viennent d'être décrits. Les femmes chantent : « Eh ! Douwa-sou est en train de planer ! Douwa-sou de Tyawa est en train de planer ! » [allusion au masque oiseau qui danse en imitant le vol du vautour]. « Ah ! Douwa-sou de Tyawa est redoutable ! ». Dans l'ancien temps, pendant une sortie du kòma, ce chant aurait été entonné d'une voix de masque, très rauque, par le danseur lui-même, les kòma den, les enfants du kòma, lui répondant en choeur d'une voix normale1.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Komo / Koma / Komodenu)

p. 199

(See Charry, 2000.) (Table 12 Occasions for Drum and Dance Events.)

p. 207

The names and specific activites of jow and tonw vary according to the region, but six have been widely recognized by researchers as being native in the Mande heartland through Segou. Ntomo and Kore are tonw; Kòmò, Nama, Nya, and Kono are jow. In essence, a ton is public, it deals with mundane matters, and its rules are human made. A jo is a secret association dealing with natural laws and supernatural powers.

Jow and tonw possess wooden masks, which are instantly recognizable emblems for their associations. The masks can take the form of elaborate vertical headdresses, face masks, or helmets that project horizontally. Horizontal helmet masks like those used in Kòmò societies are widespread in West Africa and are usually abstract depictions of bush animals (McNaughton 1991, 1992). These wooded masks are worn by dancers who are accompanied by drummers. Usually only the masks of tonw are taken out in public and danced in open performances. Well-known masks include those from the children's ton Ntomo (Zahan 1960), the agriculturally centered tonw Ciwara (Tyiwara) and Sogonikun (Sogoninkun) (Imperato 1981), and the most widespread of the jow, Kòmò (McNaughton 1970; Brett-Smith 1994).10

Jow and tonw use different drums associated with the regions where they operate. Although much important documentation has been written on tonw and jow, there is little information on the drumming that accompanies the masked dancers. In an otherwise highly informative musical account of the associations that were active in Upper Guinea in the early twentieth century, Joyeux (1924:206-7) devoted only half a page to Kòmò (Mn: Kòma), with a cursory reference to Kòmò flutes. Out of the more than one hundred named rhythms that have been recorded by jembe players, few are related to Maninka jow; the most readily identifiable one is simply called Komo, Koma, or Komodenu (Children of Komo).11 Kòmò associations are traditionally led by numus, who also carve the masks and drums used in their rituals.

10. . . . For a description of Kòmò mask performances among the Bamana see Travele (1929); among the Wasulu see McNaughton (1979:37-42) and among the Minianka see Diallo and Hall (1989:68-69).

11. For recordings see Ladji Camara (n.d.a-disc), Rouget (1972/1999-disc), Mamady Keita (1989-disc), and Yamadu Dumbia (in Polak 1994-disc).

p. 220

Taking the examples of Dundunba, Komo, and Manjani . . . it appears that jembe drumming in serious ritual contexts may have declined by the time of independence.

Colleyn, Jean-Paul, and Laurie Ann Farrell. 2001. "Bamana: The Art of Existence in Mali." African Arts 34 (4): 16-31+94.

(Kòmò)

p. 30

Kòmò and Kònò are other secret societies that can be found in Bamana regions. These jow form political networks that transcend the limits of the village. Their masks and boliw are said to symbolize an association, or marriage, with the supernatural entity.8 In contrast to Kòmò masks, which are covered with feathers, horns, and teeth (Figs. 21, 22), those of the Kònò society are elegant and simple (Figs. 23, 24).

21. Kòmò society mask in the form of a wart hog. Koulikoro region. Wood; 47cm (18.5').

22. Kòmò society mask: Warakun. Koulikoro region. Wood, animal fur, horns, porcupine quills, mirror; 76 cm (30').

Kòmò sanctuaries have spread throughout present-day Mali as well as Guinea, southern Mauritania, eastern Senegal, western Burkina Faso, and northern Côte d'Ivoire. Their style strongly reflects the influence of Arab mosques, palaces, and other types of Sudanese architecture. Traditionally led by blacksmiths, each sanctuary once exerted significant political influence, using the voice of a masked dancer to communicate messages to villagers.

Keita, Mamady. 2004. Sila Laka. Fonti Musicali, FMD 228.

(Komodenu)

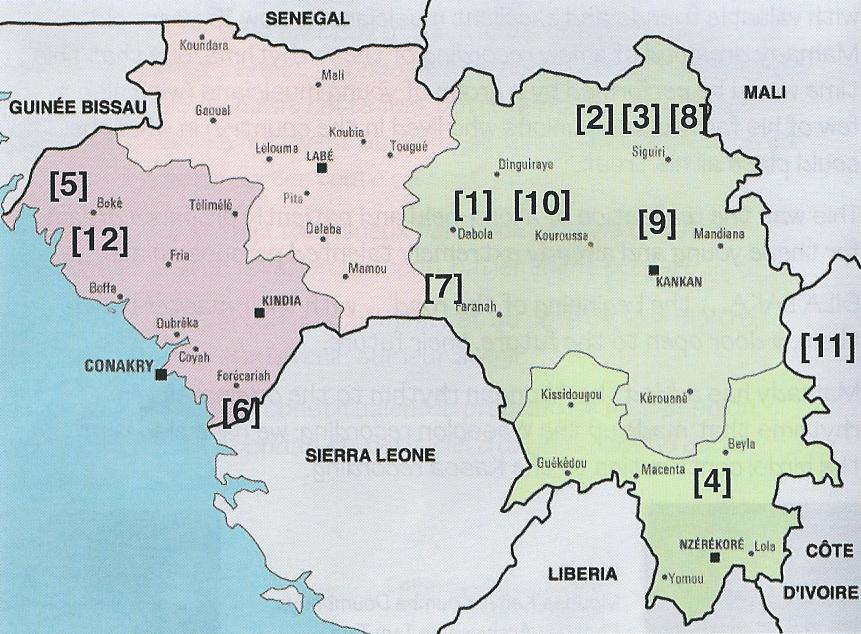

Komodenu. Nalu. Région: Boké (no. 5 on map)

Koma ou Komo est un masque, et Komodenu désigne les enfants du fétiche ou les apprentis du fétiche. Quand le Komo sort, porté par un garçon dont les qualités de danseur sont reconnues, les femmes et les enfants, qui ne peuvent pas le voir, restent dans les maisons. Aujourd'hui, en pays Nalou, garçons et filles dansent sur ce rythme lors des cérémonies de mariage.

| Eh vous! Les enfants du Komo | E Komodenu | Hey, you! Children of Komo! |

| Regardez la fumée Cela vient de Tamaniko |

Sisi bora Tamaniko | Look at the smoke That comes from Tamaniko |

| Le feu a pris dans la maison du Komo | Taa wulida komo so la | Fire has broken out in Komo's house |

| Regardez la fumée Cela vient de Tamaniko |

Sisi bora Tamaniko | Look at the smoke That comes from Tamaniko |

see also:

Brett-Smith, Sarah. 1997. "The Mouth of the Komo." RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 31: 71-96.

McNaughton, Patrick R. 1979. Secret Sculptures of the Komo: Art and Sculpture in Bamana (Bambara) Initiation Associations. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

———. 1988. The Mande Blacksmiths: Knowledge, Power, and Art in West Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Zahan, Dominique. 1960. Sociétés d'initiation bambara: Le N'domo, Le Korè. Paris: Mouton.