koreduga

Dieterlen, Germaine. 1951. Essai sur la religion bambara. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

(Kworeduga)

p. 170

La cérémonie annuelle [du korè] est une représentation de l'action des invisibles pour obtenir les pluies nécessaires aux hommes : les brûlures, les coups que s'infligent les sociétaires ainsi que les chevauchées des kworeduga symbolisent les combats célestes des génies dans les éléments déchaînés.

Zahan, Dominique. 1974. The Bambara. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill.

(Korè duga)

p. 22

The korè "vultures" or "horses" (korè dugaw) represent the spiritual joys and pleasures experienced by those who reach the stage of union with God. These feelings are expressed by the initiates of this class in a very free, even lascivious, mode of behaviour. The liberty enjoyed by a korè duga (Pl. XXXII, 2-XXXIII) sets him free from all social conventions: nothing is forbidden him; for example, he may even eat human excrements as food.

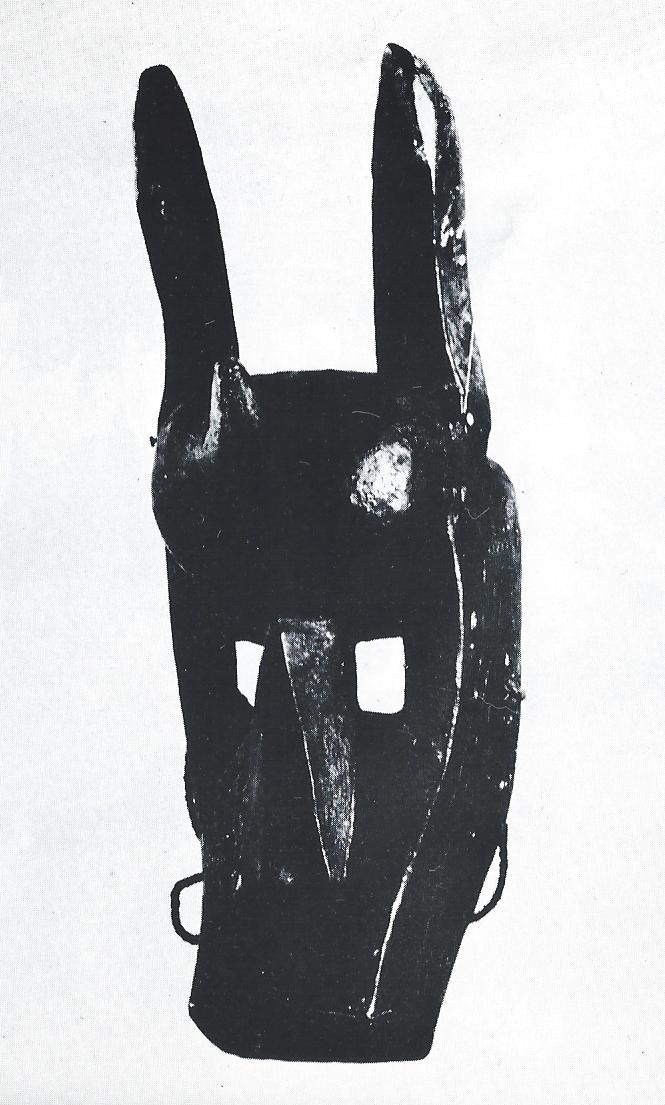

Plate XXXII Korè "horse" mask. This object has very profound and complex meanings. The korè "horse" is symbolically associated with intelligence, the spirit and intuition. It is also associated with the search for immortality and with the theft of eternity. Provenance: Mali Republic. — Dimensions: height 0.50 m., width 0.25 m. — Material: wood of kapok tree. — Collection: Musee de l'Homme. — Photographed by R. Pasquino.

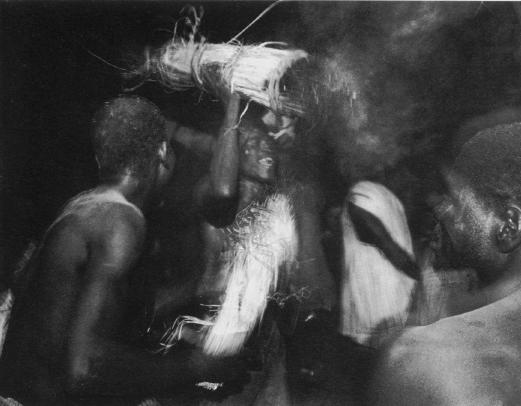

Plate XXXIII Korè duga in his ritual "equine" costume. Dressed in this attire, the korè duga indulges in wild scampers, leaps and kicks, with desperate gallops which represent man's efforts to attain immortality. Photographed by M. Griaule.

Brink, James T. 1978. "Communicating Ideology in Bamana Rural Theater Performance." Research in African Literatures 9 (3): 382-94.

(Koreduga)

pp. 388-9

The koredugaw, or buffoons, are ritual specialists of the men's kore society who are renowned for their wisdom and comedy. Playing with the structure and meaning of words and partaking in gluttonous feasts, these young men always introduce the ridiculous into everyday routines. In the prologue the actor announces he is a koreduga through a song that refers to the large quantities of food these persons are believed to eat.

The satirical or critical dimension of kote-tlon is announced in some of the songs accompanying prologue skits. In a koreduga skit, actors comment on their relation with their fathers: "Each year we prepare the fields for planting, but there are no wives for us; at the beginning of the dry season there are no wives for us; the road to the cemetery is well traveled but no one returns from there; there is no way to pay for a person's soul." Other koreduga songs set the mood of the theatrical occasion by addressing girls: "The little girl is not ashamed, the little girl is not polite; the little girl does not go near men and that little girl is not pregnant." "Little girl, tighten your waistcloth; your precious thing (= vagina) is showing; if a poor man saw the little girl's thing showing it would be easy for him to get an erection; this shame is not good at a public occasion."

Brink, James T. 1982. "Time Consciousness and Growing up in Bamana Folk Drama." The Journal of American Folklore 95 (378): 415-34.

(Koreduga)

pp. 429-30

The kaka dance gives way immediately to a few skits performed by the association's actors. The skits are collectively known as korèduga, a word used in a general sense to designate clowns, buffoons, or funny persons, and more specifically to refer to the ritual clowns of the men's korè initiation society (cf. Zahan 1960). Besides these ritual clowns, the prologue skits depict such characters as the ragged old woman, the slave, the man with a long penis, and the blacksmith woman.

Blanc, Serge. 1997. African Percussion: The Djembe. Paris: Percudanse Association.

(Koreduga)

From the Bamana ethnic group, in the Ségou region of Mali.

The koreduga caste are part of a separate group within the Bamana tradition.

They are easily recognized by their distinctive slovenly dress. Their role during the celebrations is to make the assembly laugh with their mimicry and acrobatics.

Above all else, the koreduga rhythm accompanies the dance of clowns and buffoons.

It is danced by both boys and girls.

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Kotedjuga / Koredjuga)

Traditional Ethnic Group: Malinke; Border Region Mali/Guinea

Kotedjuga is the name of a caste that still exists today.

The Kotedjuga were jesters and clowns, who, for instance, appeared suddenly at wedding festivities, in order to fool around and to make people laugh.

They intentionally "disturbed" the festive celebrations and demanded money to leave again. The behavior of the Kotedjuga was accepted, and their appearance was an integral part of traditional festivities. The song that accompanies the rhythm is called Komodemu.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Kore)

p. 207

The names and specific activites of jow and tonw vary according to the region, but six have been widely recognized by researchers as being ative in the Mande heartland through Segou. Ntomo and Kore are tonw; Kòmò, Nama, Nya, and Kono are jow. In essence, a ton is public, it deals with mundane matters, and its rules are human made. A jo is a secret association dealing with natural laws and supernatural powers.

Colleyn, Jean-Paul, and Laurie Ann Farrell. 2001. "Bamana: The Art of Existence in Mali." African Arts 34 (4): 16-31+94.

(Korèduga)

pp. 29-30

Bamana people perceive Korè as the "father of the rain and thunder." Every seven years a new age-set of teenagers experiences a symbolic death and rebirth into the Korè society through initiation rituals whose symbols relate to fire and masculinity.

Initiations take place in the sacred wood, where the youths are harassed by elders and the clown-like performers called korédugaw [sic].7

Until the 1940s, initiates practiced a form of ritual dueling with whips. Today, however, the rituals are less severe. Furthermore, while many original types of Korè masks have been phased out and distinctions between ritual groups made less evident, initiates traditionally belonged to a several different groups, each having its own masks (Figs. 18, 19). In their general form and detail, a group of Korè masks . . . conveys concepts such as knowledge, courage, and energy through the representation of hyenas, lions, and other animals.

18. Korè society mask: Suruku (hyena). Koulikoro region(?). Wood, animal hair, metal; 53cm (20.9').

19. Korè society admission ceremony, the first step of initiation. Nyizensso, 1997. Photo: Catherine De Clippel.

p. 94

7. The korèdugaw form a special class by themselves. They often belong to groups distinct from the Korè. These ritual buffoons participate in public events and imitate hunters and warriors with pretend guns and wooden horses. As powerful people, the latter are expected to tolerate the mockery.

see also:

Zahan, Dominique. 1960. Sociétés d'initiation bambara: Le N'domo, Le Korè. Paris: Mouton.