lamban (sandia)

Knight, Roderic, prod. 1972. Kora Manding: Mandinka Music of The Gambia. Ethnodisc, ER 12102.

(Lambango)

Lambango is said to be the oldest song in the Manding repertoire, played originally on the balo. It is one of the only songs which has a dance associated with it and was performed as a diversion for the jalolu themselves rather than being dedicated to any one person. Over the years it has become customary to sing about Sunjata when performing it [...].

The vocal phrases of of Lambango are generally of the Sataro type, though in this performance some will bear a resemblance to each other and suggest the donkilo type instead. Musa Makan provides spoken commentary and encouragement to the singer, resulting in a very spirited performance.

The tuning for Lambango is Sauta.

| Yamaru O, keme nila. | Hail, hundred-giver. |

| Fen ka di ngaralu male | That is pleasant for the skilled singer |

| Awa, n na jon nila | Well, my slave-giver |

| (Namu!) | (Yes!) |

| Bee togo be ko. | Everyone's name remains [after they've gone]. |

| Ali nin wura la. | Good evening to you all. |

| Ali nin wura jaliya la. | Good evening and welcome to the entertainment. |

| Ali nin sumun jaliya la. | Welcome to the evening's visiting. |

| Jali musu ma fara a kema kan siwawa. | The jali woman and her husband join in shouting praise. |

| E, ali bunya be jaliya to | Eh, you're respected for your abilities [Spoken out of respect for other performers present.] |

| Jaliya mu m bemba ke ti. | Entertainment was the profession of our ancestors. |

| (Namu! Musa Makan Suso, wo le be jaliyala Kerewani jan, anin Jali Keba, anin Fatumata Jebate, Kerewani-dumbo-kono.) | (Yes! I am Musa Makan Suso, entertaining at Kerewan here, with lali Keba and Fatumata Jebateh, at Kerewan-inside-the-jar.) |

| Jalindin fara jaliba kan | Entertainers great and small alike |

| Ni i be nala 'waye' folola | When you begin a song |

| Ni i ma folo Jata Jan na | If you don't start with the Great Lion (Sunjata) |

| I s'a laban Jata Jan na wala. | You will necessarily end by mentioning him. |

| (Nyankumolu kabala, Simbon nin Jata be Narena.) | (The cats are running, Simbon and lata are at Narena.) [both names for 'lion'] |

| Jata Suba, Dan Suba, Maka Suba | [Praise lyrics for Sunjata] |

| Bera san keme la | Buy land for a hundred [A foreign king required Sunjata to buy the land for his mother's grave] |

| (Namu!) | (Yes!) |

| Ala nin Mama Delin Suma Jata. | God with Grandfather Delin Suma lata. |

| Bera bukuto san keme la | Buy the sand for a hundred |

| Ala nin Mama Delin Suma Jata. | God with Grandfather Delin Suma lata. |

| Kolon san keme la | Buy the well for a hundred |

| Ala nin Mama Delin Suma Jata | God with... |

| Delin tikan kan jo | Delin, cool your anger [?] |

| Delin tikan kan suma | Delin, cool your anger [?] |

| Nyagamba Deniyan | [Praise for Sunjata] |

| (Namu!) | (Yes!) |

| Kuru Deniyan, Toke Deniyan | [Praise names for Sunjata] |

| I nin wura! | Good evening! |

| (Namu!) | (Yes!) |

| E, Ma Buraima Konate man sila tinya abada. | Eh, Ma Buraima Konateh didn't ruin his life at all. |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Sunjata O, Mali mansa. | Sunjata O, king of Mali. |

| (Yo!) | (Yes!) |

| Sunjata O, Ma Buraima Konate man sila tinya abada. | Sunjata O, Ma Buraima didn't ruin his life at all. |

| (Wolahi! Ni i ye siseo je lo nyinina noma, a man nyo surala le je.) | (To God! If you see a chicken following the woodcutter, he hasn't seen the millet pounder.) [A jali knows where his profit lies.] |

| Kenye nin Delima | [Praise names for Sunjata] |

| Delima nin Kenye ma Suma | [Praise names for Sunjata] |

| Wolu le mama bota | Their grandfather has come |

| Fela nin Madula te | Between Fela and Madula |

| Madula nin Fela te | Between Madula and Fela |

| (A!) | (Ah!) |

| E, mansa nyiman! | Eh, beautiful king! |

| Duniya le keta m bulu la | Life is hard on me |

| Kutumbun teleta ka ta m ban na | Good things have fallen apart, trouble has come |

| Wo to keta m bulu la, kantambali kanya ti. | The world has changed. What the jali got before is no more. |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Jali kana malu jaliya la | Jali, don't be ashamed of your profession |

| Manan kun t'e bulu. | You don't have the capital to start another. |

| Ntelu le ka nganalu lon | We are the ones who know the celebrities |

| Nganalu ka n fanan ion. | The celebrities in turn know us. |

| Bulu ngana nin da ngana te kilin ti wala | Those who do something and those who just talk are not the same |

| Ngana koni man siya, jan bi n don na | The great celebrities are few today.... [?] |

| (Wolahi, nganalu kili de!) | (To God, call the celebrities there!) |

| Li li lu la la | Li li lu la la |

| Nyakan Turu jamani, ku bee kanu mansa | Nyakan Turu's time, the omniscient king |

| Duntumba le ko, 'An Jabirun, An Jabarun!' | The big cock crows' An Jabirun, An Jabarun!' [Praise of Allah] |

| (Namu!) | (Yes!) |

| E, sogo bee ni i yele kan | Eh, every morning has its sunrise |

| Kuma bee n'a fo lun. | Every word its time and place. |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Mansa bee ni i tili le mu | Every king has his time to rule |

| Musu bee ni i ke le fana mu | Every woman has her husband too |

| Din bee ni i fa le mu | Every child has a father |

| E, n fa duniya! | Eh, my father's world! |

| Mogolu b'a fola ko, 'duniya tinyata' | People are saying the world is lousy |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Kuru man tinya, yiri man tinya | The kola nut is not rotten, the tree is healthy |

| Hadamadin mogolu tinyata. | It's the people who are lousy. |

| (Wolahi. tonya!) | (To God, that's true!) |

| Ntelu le ka mansolu lon | It is we who know the kings |

| Mansolu ka n fanan lon. | And the kings too know us. |

| Jan muta n ye manso, wo nin manso te kilin ti wala. | The temporary leader and the leader are not one at all. |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Jiki O Bala! | Hope, oh, Bala [Musa]! |

| (Wo mu Bala juma le ti?) | (Which Bala is that?) |

| Jiki O Bala banta, nya nani Musa. | Bala, our hope, has died, four-eyed [fearless] Musa. |

| (Namu!) | (Yes!) |

| Wo diyata Bala men na | The Bala who liked that [song] |

| Kanimunku kumbengo diyata Bala men na | The Bala whose days at Kannifeng were good, |

| Nya nani Musa. | Four-eyed Musa. |

| Ate le ka janjungo ke dula siyaman | It was he who ventured many places |

| Wolu bee janjungo diyata Bala la, nya nani. | Those ventures were all successful for him, four-eyed. |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| A diyata Bala men na | The Bala who liked that [song] |

| Kanimunku kumbengo diyata Bala men na | The Bala whose days at Kannifeng were good, |

| Nya nani Musa. | Four-eyed Musa. |

| Ali banna mansolu lala | You have compared the kings |

| Mansolu man kilin wala | Kings aren't all the same, for sure |

| Ko, fa den manso nin manso te kilin ti wala. | Say, the father's child [enemy] king and [ordinary] kings are not one at all. |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Jiki O, Bala banta. | Hope, oh. Bala has died. |

| (A! A buka silo tinya.) | (Ah! He never ruined his life.) |

| Muna, itelu m'a lon? | Behold, don't you know? |

| Mogo lon balo si mogolu kanyan ne | Someone who doesn't know people will say they are equal |

| Mogolu man kilin wala. | People are not all the same, not at all. |

| (Mogolu janfata nyo la.) | (People are very different from each other.) |

| Ala kibaru, fa duniya, Ala kibaru | God Almighty, father's world, God Almighty |

| E, kuha jama le tambita wala. | Eh, many great events have passed, indeed. |

| Jiki O Bala banta, Bande banna | Hope, Bala, has died, wealthy Bandeh |

| Diko nin Fa Nyamen | [Praise lyrics for the Fula people] |

| Koli ngana nin ten kala banna. | Koli the notable and... wealthy. |

| Mogo men ka Fulo lon | If you know one Fula |

| Ni i man fulan jan lon | But haven't met a second |

| Fulo b'e mone la, Bai Gile. | The Fula will surprise you, Bai Gile. |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Ha Kari nin Juman Kari | [Praise names for Fula] |

| Tili mans a din nin wura la | Good evening to the Sun King's child |

| Nyani Kale jombaajo. | Kale, bride from Nyani. |

| (Namu! A nin kelo fele larin Keserikunda.) | (Yes! He and the war have both been laid to rest at Keserikunda.) |

| Fulo, Fulo, Mbai Gile | Fula, Fula, Mbai Gile |

| Ate le man na | Didn't he come |

| Jon ke nill jon muso di | To give a man and a woman slave |

| M baba Jali Fili ma bee nya la? | To my father Jali Fili, for all to see? |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Jiki O Bala, safuna kumba le mu Bala ti | Hope, oh. Bala; Bala is like a great bar of soap |

| N'a man jigi ko to, musolu me seniya abada. | If he didn't go into the water, the women would not be clean at all. [Musa is to the people as soap is to washing.] |

| I sarna, Jara lolo | Good morning, Jara the star |

| Ni i man ho san men, solimalu me keneke na | The year you don't come, the uncircumcised will not be clean. |

| Ala kibaru, fa duniya lon man di. | Great God, understanding the father's world is not easy. |

| (Wolahi!) | (To God!) |

| Ali be m bulala jaliya la | You are putting me to work at entertainment |

| Jaliya man di. | Entertainment is not easy. |

| (E, wolahi!) | (Eh, to God!) |

| Kele tigi nin ma tigi man kan | A warrior and his men are not the same as a ruler and his followers. |

| Jon kun tigo nin banna nte kilin ti wala | The slave master and the wealthy are not the same at all. |

| Jiki O Bala banta, nya nani Musa. | Hope, Bala, has died, four-eyed Musa. |

| (E!) | (Eh!) |

King, Anthony P. 1974. "Musical Tradition in Modern Africa." Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 123 (5221): 15-23.

(Lambango)

p. 19

Charters, Samuel, prod. 1975b. The Griots. Ministers of the Spoken Word. Folkways, FE 4178.

(Lambango)

We are singing Lambango,

a song that is meant for the griots.

We sing to it and we dance to it.

Here we call for our honourable patrons who care for us.

We call for the griots who honor our profession,

the art of singing and dancing for our patrons.

We thank God who created the earth and man kind.

Oh the world and its creatures.

I am singing and calling for my patrons,

patrons who are traders.

Patrons like the Dabos, who is my host—Aliu Dabo!

We call for our honourable patrons

who feed and cloth us.

Many days have gone and many days are to come.

Many great people have gone

great men we griots will never forget.

Jobarteh, Amadu Bansang. 1978. Master of the Kora. Eavadisc, EDM 101.

(Lambang Silaba)

Lambang Silaba (The main Lambango).

The piece called Lambango exists in many versions, of which this is the most common. Originally a balo tune. it is generally regarded as being one of the oldest pieces in the repertoire. The musicians regard it as their 'own' tune, which they perform for their own entertainment; it is one of the only kora items with an associated dance, which is performed by the women. There is no particular text attached to it other than the refrain, though it is common to make reference to the story of Sunjata (the founder of the Manding Empire) since he was the first patron of Jalis. In this peformance Amadu refers first to Sunjata, quoting some of his praise names. The 'cats on the shoulder' line is derived from an incident in Sunjata's early life when, penniless, he chose to feed his musicians on cats rather than give them up.

All young musicians are first supposed to learn this line in order to understand the importance of the Sunjata story in the musicians' repertoire. In the second half of the song, Amadu refers to the 19th century King Musa Molo of Fuladu. 'Bala' is the common nickname for anyone with the name of Musa (Moses), and Bijiim and Jenyeri are places where he fought important battles. As Musa Mojo was Fula, Amadu addresses the last line to him in the Fula tongue.

Such texts do not stand well in translation, but to a Mandinka audience each praise name would conjure up the stories of the heroes with which they are associated. Lambango is played here in Sauta tuning though it may also be played in Hardino.

Refrain

Ah, Music! It is God who crtated music.

God, who created music,

It was He who created kingship.

All things are in the hands of the Immortal.

Recitation

When a young musician is learning the art of singing

When he has reached that point,

He must first say, 'Cats on the shoulder

Simbong and the Lion are at Naarena.'

Makhara Makhan Konnate.

The name Simbong refers to freedom and bravery.

The Lion had his fill of royal inheritance.

Powerful hunter!

Ah world, the world of our fathers,

You have vanished forever.

At the time of the great kings who performed great deeds—

Times were good then.

But now they are all over.

Oh Bala, adventure-seeking Bala. beloved son of his nurslng mother,

The Bala whose battle in Bijiim was successful,

The Bala whose battle in Jenyeri was successful—

I am speaking to you

(Refrain)

Knight, Roderic. 1982a. "Manding/Fula Relations as Reflected in the Manding Song Repertoire." African Music 6 (2): 37–47.

(Lambango)

p. 39

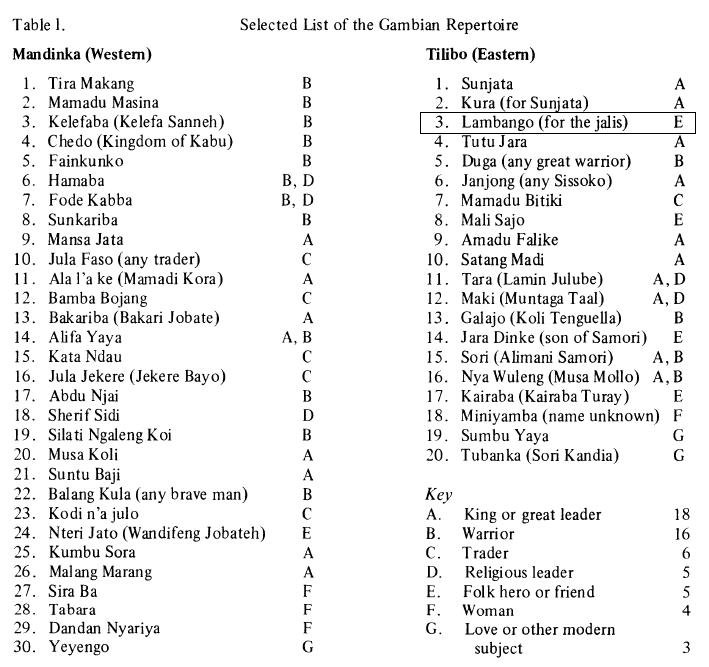

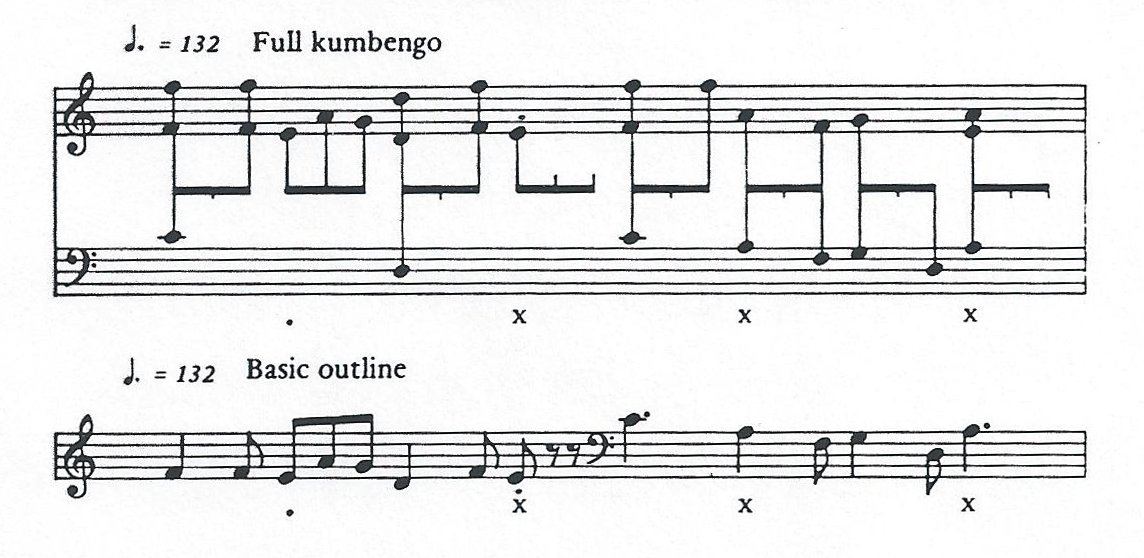

Table One . . . includes the best known, most often heard, or otherwise significant songs in the [Gambian] repertoire. In each column the top few songs are the oldest, and the bottom few are the youngest. The majority in each case fall somewhere in between (often in the nineteenth century), but no chronological ordering beyond this is intended, since it is often not possible to date a song exactly. Most of the songs bear the name of their owner as the title. Where they do not, his name is shown in parentheses next to the title. The letter code at the right represents the person's "claim to fame" or calling in life, as shown in the bottom of the list.

p. 40

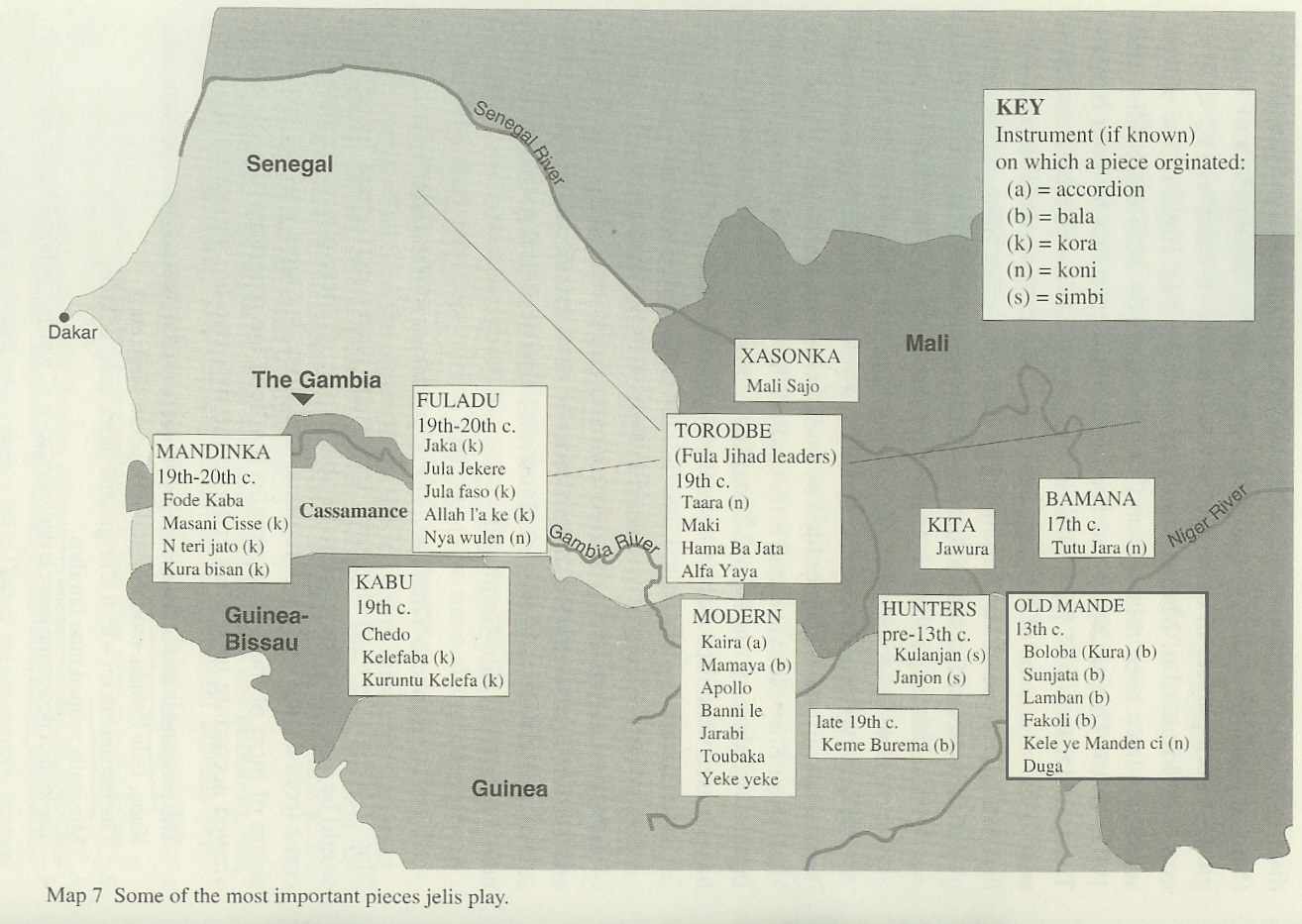

Table Two shows the same fifty songs again, grouped this time by the ethnic background of the people commemorated.

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Lambango)

p. 32

"Faringbulo" was the first piece of music that nine of the jalis [of the twenty interviewed] learned to play, "Lambango" was the first tune for four others. "Kelefaba" and "Jakaa" were learned first by two other jalis. In addition, ten of the jalis said they learned to play songs in a set order. Yet no two jalis listed the songs in the same order.

pp. 101–5

Donkilo (on teaching tape)

| I ye jaliyaa | Ah the art of being a jali, |

| Ala le ka jaliyaa da | It was God who created the art of being a jali. |

Background to "Lambango"

During Sunjata's time (13th Century), there was an occasion when all the balafon players gathered together. They said, "We should have our own tune, which we can dance to ourselves."

So it was on that day they invented "Lambango" for the jalibas to dance to. It became a general tune for all the jalis, which they used to play and dance to, to entertain their heroes, kings, and patrons.

Although it originated as music for the balafon, it is also played on the kontingo. There was a kontingo player named Lamin Dambakateh who modified "Lambango" to its present style, by changing the tune a bit. Lamin Dambakateh was about to marry a very famous jali woman, Bantang Kuyate, who was an excellent singer and historian. One day Lamin left his village to visit Bantang. Unfortunately, before he arrived, she died and was buried. Upon his arrival he was told the sad story. He asked the people to show him Bantang's grave. He went there with his kontingo and played a special version for his dead fiance.

"All is possible, Bantang Kuyate, (but) Beauty will not prevent death."

This modified version of the melody has since become the standard "Lambango" and the original version is no longer played.

pp. 146–59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Lambango |

| Translation: | |

| Dedication: | Jalolu themselves, also Sunjata |

| Notes: | dance associated with it |

| Calling in Life: | Jalolu |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | E (13th & 14th c.) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

| Title | Lambamba |

| Translation: | Big Lambango |

| Dedication: | |

| Notes: | dev. from Lambango |

| Calling in Life: | king or leader |

| Original Instrument: | Kora |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | L (after WWII) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

Kante, Mamadou. 1983. Drums from Mali. Playasound, PLS-65132.

(Sandia)

Sandia means "Happy New Year" in the Bambara language. This dance is interpreted by the griots from the Manding area.

Haydon, Geoffrey, and Dennis Marks, dirs. 1984. Repercussions: A Celebration of African American Music. Program 1. Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia. Chicago: Home Vision.

(Lambang)

Lambang: A piece played by jalis for their own entertainment. The husbands play for their wives to dance—jaliyaa for jalis; music for musicians. The chorus goes: "God created the art of music."*

* Transcription mine. Orthography based on Jatta (1985).

Knight, Roderic. 1984. "The Style of Mandinka Music: A Study in Extracting Theory from Practice." In Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, vol. 5, Studies in African Music, ed. J. H. Kwabena Nketia and Jacqueline Cogdell Djedje, 3–66. Los Angeles: Program in Ethnomusicology, Department of Music, University of California.

(Lambango)

p. 25

There are four standard konkondiro patterns.

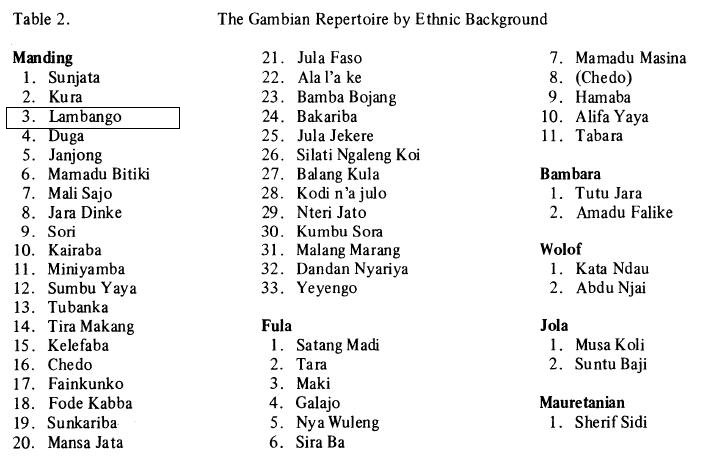

I: "Lambango." Of the metronomic konkon rhythms, one is by far the more common. It consists of three taps and a pause in any order, such as x x x · or · x x x or x · x x. This pattern moves slowly, clearly marking off four equal subdivisions. It is appropriate or many of the older pieces, especially those that originated as balo pieces in the Tilibo repertoire. We shall refer to it as the Lambango pattern, after what is reputed to be the oldest piece in the repertoire. The kumbengo and konkondiro for "Lambango" as played on the kora are shown in Ex. 17 and heard on Tape Ex. 5.

Example 17. "Lambango," with konkondiro (Tape Ex. 5)

p. 30

"Lambango," mentioned earlier as one of the oldest songs, . . . appears to have no donkilo--only a few sketchy phrases to get the song going, and then uninterrupted sataro.

pp. 40–51

"Lambango:" A Classical Example of Tilibo Sataro

"Lambango" is regarded as one of the oldest songs in the repertoire. It is a song which the jalolu perform for themselves and one of oly a few songs that have a women's dance associated with them. The text is for Sunjata. In the performance to be studied, four sections may be noted.23 The singer, Fatumata Jebateh, begins with standard opening phrases, turns to standard praises of Sunjata, then to a variety of proverbs and other observations and comments. Finally she begins to sing about another great leader, Musa Mollo, the last king of the Fuladu region of Gambia, who died early in this century. We shall examine the first four minutes of this performance, including the first two of these sections and part of the third, for a total of fifty-one phrases.

(See Knight [1984].) (Transcriptions, Analysis, and Discussion.)

This performance may be heard on Ethnodisc ER 12102, A-1. The excerpt corresponds to the first two pages of Mandinka text in the accompanying booklet, pages 18 and 20.

Jatta, Sidia. 1985. "Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia." In Repercussions: A Celebration of African-American Music, ed. Geoffrey Haydon and Dennis Marks, 14–29.

(Lambango)

p. 23

. . . jalis bearing the patronym Kuyaate claim that Lambango was originally composed for their wives.

p. 24

Lambango is traditionally played by jalis for their own entertainment. The husbands play for their wives to dance—jaliyaa for jalis: music for musicians.

Sacko, Ousmane. 1987. La nuit des griots. Recorded 1983. Ocora/Harmonia Mundi, HM CD83.

(Kono yadan ba — Lambamg [sic])

According to oral tradition, Lambang is one of the oldest pieces in the Manding repertoire, dating back to the tme of Sunjata (13th century). It was originally played on the bala and today exists in many variants, all based on a short circular melody which accompanies a graceful swaying dance performed exclusively by the female jalis. The traditional Lambang song praises the art of music, but here Ousmane Sacko has composed a new refrain in honour of his patron, Surakata Kebe. He also makes some biting comments about Malian society, while Yakare sings standard praise lyrics for Yusuf Tata Cisse. During the lively instrumental interlude, the bala improvises variations in accompaniment to Yakare's dancing.

"Kebe has shown us great generosity; Kebe, you are free like a bird, so fly on. There is no recipe for success, it is God-given; therefore it is pointless to be jealous of the successful musician. People nowadays don't stop at anything! If a young girl has an ornate hairstyle they say she's being coquetish, but if her hair is simple they accuse her of neglecting herself. If a woman dyes her feet with henna, people will say she's up to mischief, but if she does't they accuse her of being dirty. If I buy a beautiful robe people say I'm acting like a dandy, while if my shoes aren't brand new they say I'm unkempt."

Yakare: "I'm singing for the trader Youssouf Tata Cise. The Cisse are the holy men of manding. You can't compare the singing jali with one who has no voice. Youssouf Tata Cisse, you are trustworthy; not all mothes are blessed with good sons, but your mothers are blessed with you. Not everyone is generous with musicians, but you are. When people are away from home in a new environment they are not always trusted, but you inspire trust everywhere. One must speak well of those patrons who are generous to jalis!"

"Not everyone has the ability to speak in public—one must leave this to the jalis. The jalis who can't speak in public have left it up to me. Those who are unable to give anything to the jalis should leave it up to kebe. And he cannot hold a "bic"—leave it to Cisse, the historian!"

Kouyate, (El Hadj) Djeli Sory. 1992. Guinée: Anthologie du balafon mandingue. Vol 2. Buda, 92534-2.

(Lamban)

A tune dedicated to the griots who host a ceremony in their house.

Jobarteh, Amadu Bansang. 1993. Tabara. Music of the World, CDT 129.

(Lamban)

Lamban is one of only several kora pieces that was created by jalis for their own entertainment. The piece has not been traced to any particular story or legend, and probably originated on the balafon. Malian jalis often play this classic piece to relate any event they may wish. Like Tabara, Lamban is also played in sauta tuning. Amadu's interweaving of kumbengo and birimintingo illustrates the depth of his musical prowess.

Charry, Eric. 1996. "A Guide to the Jembe." Percussive Notes 34 (2): 66-72.

(Jeli don)

p. 68

Some rhythms honor groups of people, such as Jeli don (jelis), Woloso don (a class of slaves) or Dundunba (strong or brave men). (In Maninka, "don" means "dance.")

Kouyate, M'Bady, and Diaryatou Kouyate. 1996. Guinée: Kora et chant du N'Gabu, Vol 2. Buda, 92648-2.

(Landan)

This tune is dedicated to griots whenever they host a ceremony.

Blanc, Serge. 1997. African Percussion: The Djembe. Paris: Percudanse Association.

(Sanja)

From the Maninka ethnic group, in the Kayes region of Mali

This piece traditionally opened the ceremonies for the death of a king or a very important man.

Recounting the Mandingo epic, this predominantly vocal rhythm was interwoven with "Fasa".1

Traditionally, the real sanja is not played on the djembe, which is not a griot instrument like the bala, the ntama and the jalidunun.2 Only these instruments accompany the sanja, played to honor men and women griots. On these occasions, the griots sing each other's praises and execute this very graceful dance with circular movements, their arms spread out. Today, some associations organizing "Ambianci Foli"3 ask the djembefola to play the sanja. He can only do so in these kinds of modern circumstances. This rhythm is also called jalidon4. In Guinea, it is called lamban.

1. Songs of praise.

2. Griot dunun.

3. Neighborhood festivities.

4. Dance of the griots.

Mandeng Tunya. 1997. M'Fake. Mandinka Magic Music. U.S. cassette.

(Lambang [Lamba])

One of the few songs designed to entertain griot clan members, griot families only play this song when amongst themselves. Lambang is accompanied by the jalidon, the griot dance. When the moon is bright the men come out and play the kora and balaphone while the women dance and sing the Lambang song. Music is created by God and God created us to play good music and dance.

Sissoko, Djelimoussa "Ballake." 1997. Jeli Moussa Sissoko: Kora Music from Mali. Bibi B. Bucking Musikverlag/Nbg., 9764-2 Indigo.

(Lamban)

"God has created jeliya, god has created royalty. Only a man of honour can turn a little griot into a big griot..."

Lamban is dedicated to the Kouyate family, the first griots. The descendants of Balla Fasseke Kouytae, the griot of Sundiata Keita, are the guardians of the tradition. Several regional variations of Lamban exist. Jeli Moussa plays the Lamban of Manden (the former core area of the Mali empire between northern Guinea and southwestern Mali) in the electric sumun style of Bamako.

Suso, Foday Musa, and Bill Laswell. 1997. Jali Kunda: Griots of West Africa and Beyond. Ellipsis Arts, CD3511.

(Lambango)

p. 46

When Griots feel happy, they dance the lambango, the Griot's dance. We gather when the moon is bright—the village is usually very dark at night, so the bright moon is a cause for celebration. We sing, We are Griots, God made us Griots. God gave the Griot people the musician's art. All of our songs are about other people, but the lambango is for us.

pp. 48-9

Griot family in the tiny village of Tabato, Guinea-Bissau dances the lambango.

pp. 75-6

A Griot song and dance celebrating the Griots themselves, praising God for giving them the art of music. Griots rejoice in this ancient song that is played in many villages, especially on moonlit nights.

| Ye, jaliya-o, Allah le ka jaliya da | Oh music! God created music. |

Bangoura, M'Bemba. 1999. Fandji.

(Lanban)

Marriage music of the Malenke people.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Lamban)

p. 146

79. . . . Kouyate opened her performance with a regal rendition of Lamban, a piece traditionally belonging to Kouyate jelis, and immediately went into the classic history of the Diabate lineage, citing the two Traore hunter brothers as well as Tiramakan Traore. Her choice of Lamban signalled a jeli orientation . . .

p. 148

p. 150

Many of the pieces associated with old Mali are believed to come from the bala (such as Boloba, Sunjata, and Lamban) . . .

p. 151

I call one such set the Sunjata complex, not to be confused with the set of pieces that can be performed during a rendition of Sunjata Fasa (the Sunjata epic). The pieces Sunjata, Lamban, and Boloba all have similar harmonic progression (transcription 13), yet they differ enough in their realizations so that they are not spoken of as musically related.

pp. 152–53

The bala is one of the most potent symbols of Mande identity, as is the body of music associated with it surrounding the early formation of the empire. That music is exemplified in three musically related pieces that make up what I call the Sunjata complex: Sunjata fasa, a series of praise songs and narratives that recount the history of the Mali empire; Boloba (called Kura in the Gambia), dedicated to Sumanguru Kante; and Lamban, created by the Kouyate jelis as a celebration of being a jeli. . . . Boloba and Lamban hold unique places in the jeli’s repertoiry. . . . Lamban (Md: Lambango) is perhaps the only pre-twentieth-century piece dedicated not to any single person but to the whole Kouyate lineage of jelis, and it has become one of the most popular musical vehicles used by jelimusolu in Mali to create new praise songs for their patrons. Lamban is also one of the few pieces that has a specific dundun part to it, indicating that it is also a dance piece, and indeed there are distinctive movements associated with it danced by jelimusolu (see Knight 1992-vid). The bala-based piece Mamaya, created by Dioubate (Diabate) jelis in Kankan in the 1930s or 1940s, perhaps in collaboration with Kante jelis from the area, appears to be inspired by Lamban, not so much in its musical content but as a celebratory piece by and for jelis (and their non-jeli age-mates) with a distinctive dance associated with it. The same Lamban three-stroke dundun pattern can also be played for Mamaya.83

83. . . . Panneton (1987:231–32) has drawn up a list of fifty-eight pieces in the repertory of bala players from Tabato, Guinea-Bissau, in the order in which he learned them from his teacher Umaro Jebate; the first is Lamban (Laa ban).

pp. 184–85, 187

(See Charry.) (Bala transcriptions w. discussion.)

p. 198

With a few exceptions, such as hunters dancing to sounds of their harps and the dance pieces Lamban and Mamaya played on the bala, drums are the instruments of choice for dancing.

p. 230

. . . Jeli don (also called Lamban or Sandiya) . .

p. 248

The earliest written source specifically indicating that Mande music was being played on the guitar may be Fodeba Keita’s (1948) Chansons du Dioliba, a twenty-to twenty-five-minute play consisting of one actor rendering Keita's poetry accompanied by a guitarist. . . . In a collection of works published in 1950 as Poèmes africainees, Keita continued this idea, naming pieces from a wide variety of regions and historical eras, including . . . Lamban, one of the oldest bala pieces . . .

p. 249

The earliest nonstudio recordings of Mande music played on a guitar may be those made by Arthur S. Alberts in Kissidougou, Guinea, in 1949 . . . These recordings demonstrate that a Mande guitar style had developed by then and was well integrated into the jeli tradition. They show a broad knowledge of the repertory of the jeli, including Lamban, Sakodugu, Sunjata, and Nanfulen. One of the guitarists often sang along with his guitar lines and appears to have been the leader of the group, which also inc1uded a female singer.11

11. Several older musicians from Kissidougou, Kankan, and Siguiri whom I interviewed could not identify the guitarist or vocalist recorded by Alberts in Kissidougou, but they noted that the singer was young and inexperienced. They also recognized the vocal dialect as probably coming from Siguiri.

p. 285

In Guinea, Sunjata, Tutu Jara, and Lamban hardly figure in the modern orchestra repertoires.

p. 290

In F tuning (transcription 27, Taara 2) the bass E string is tuned up to F and the B string up to C. This may be the most popular tuning among present-day Malian guitarists. F major mode pieces that exploit the natural fourth degree (B-ftat), such as Lamban and Taara, as well as F Lydian mode pieces exploiting the sharp fourth degree (B), such as Tutu Jara, may be played in F tuning.48

p. 323

The piece called Lamban (Md: Lambango) is the one of the few I encountered in which Jobarteh had names for some of the different accompaniments.

ABJ: This is balanding [little bala] kumbengo. It came from the bala, all of this came from the bala. . . . Balanding kumbengo, yes, you know if you want to play with a bala this is very good. . . .

EC: First, you started with . . .

ABJ: Lambang silaba [main way]. I left that one and went to Nganga kumbengo. I left that and I came to this balanding kumbengo. (Jobarteh 1990-per: A353–56)33

The qualification silaba (main road, main way) refers to a standard accompaniment pattern.

pp. 398–401 (Appendix C: Recordings of Traditional and Modern Pieces in Mande Repertories)

Bala: Lamban

Sory Kandia Kouyate ([1973] 1990)

Amadu Bansang Jobarteh (1978,1993)

Ousmane Sacko (I yee i y'ata, 1987)

Ami Koita (Banny Kebe, 1986; 1992)

Tata Bambo Kouyate (Mah Drame, 1988; 1995)

Hadja Soumano (Sosso, 1988)

Walde Damba (Balabolo, 1989a; Lamba, 1989b)

Suso and Laswell (1990)

Wassa (Sikiri, 1991)

Konte and Kuyateh (1992)

Amadu Bansang Jobarteh (Knight 1992-vid)

Soungalo Coulibaly (Ya Marouwo, 1992)

Diabate Family of Kela (Jeliya, 1994)

Konte, Kuyateh, and Suso (1995)

Toumani Diabate (Cheick Oumar Bah, 1995)

Diaba Koita (Seben Djara Seben and Waye, mislabeled as Ndiaye Makhanse, 199?)

Ladji Camara (n.d.a)

Mariam Kouyate (Dendiougou, Silama Kamba, n.d.)

Mariam Kouyate, Mamadou Diabate, and Sidiki Diabate (Assa Cissé, 1995a)

Morikeba Kouyate (1997)

Kerfala "Papa" Diabate (1999)

Toumani Diabate with Ballake Sissoko (1999)

Konate, Famoudou. 2000. Hamana Föli Kan. Buda, 82230-2

(Lamban)

The God who created kings also created griots to sing their praises. In a powerful shower of words, they pay tribute to the good deeds of great heroes of the past and to the contemporary efforts of revered figures. The impressive La Lamban [sic] dance remains the prerogative [sic] of the griot women and men in their grands [sic] boubous.

Jobarteh, Dembo. 2003. Listen All. CD Baby.

(Lambango)

Griots play many songs, but lambango is the one that makes us really happy.

Bangoura, Mohamed "Bangouraké." 2004. Djembe Kan.

(Lamban)

From the Manding region of Guinea and Mali.

Lamban is a griot rhythm. Griots are responsible for carrying on the traditions and telling the stories, songs, rhythms and dances. This rhythm is a celebration of the griot tradition and is the most important. The song tells of the griots coming from their village with smiling faces and joy. It says that to be a griot is a gift from God, a gift of music and dance. It is very important for me to record Lamban as I am from a griot family and music is my family tradition.

Camara, Alkhaly. 2004. Xylophone Masters: Guinea; Alkhaly Camara, Vol. 1. Marimbalafon, MBCD001.

(Lamban)

Song in honor of Musicians ("Jely").

Knight, Roderic, dir. 2005. Mande Music and Dance: Performed by Mandinka Musicians of The Gambia in the Late Twentieth Century. Lyrichord Discs, LYRDV-2001.

(Lambamba)

pp. 14–15

[The jali ensemble performs "Lambamba"]

| Ye, jaliyaa, Allah le ka jaliyaa da. | Yes, jaliyaa, it was Allah who created jaliyaa. |

| Ye, i mansayata, i mansayata le. | Yes, you have become king, you have become king indeed. |

| Keletigi-o, i mansayata, Allah ka di i ma. | Champion of war, you have become king, Allah has awarded you. |

pp. 24–25

To close this segment, we see a brief performance by Amadu Bansang Jobarteh, whose music has been playing in the background. Here he performs "Lambamba," or "Lambang Silaba." It is one of the only pieces in the jaliyaa repertoire that has a dance associated with it, and the women of his compound demonstrate it as he plays.

The sound, not in sync, is from Jobarteh's recording of "Lambang Silaba" on Amadu Bansang Jobarteh, Master of the Kora, used by permission.

| Jaliyaa, Allah le ka jaliyaa da. | Jaliya, it was Allah who created jaliyaa. | |

| Kuo bee, julo bee, sa balila. | All things, all ways [of Allah] refuse to die. | |

| Jalinding fara jaliba kang. | The young jali follows upon the elder. | |

| Meng be wawala, aning meng te wawala, | Those who sing, or even those who don't, | |

| Ni i be na wayela, i s'a folo: | If you are going to sing, you must start with: | |

| [praise lyrics for the Keita surname] | "Nyankumolu kabala, simbong ning jata be Narena." | "The cats are running, the simbong tree and lion are at Narena." |

pp. 28–33

"Lambamba" or "Lambang Silaba," meaning "Big Lambang" or "Lambang, Main Way" is a song performed for the enjoyment of the musicians themselves. It is also known as "Manding Bulo" or "Manding Julo" ("Manding Hand" or "Manding Tune"). It was originally played on the balo. According to tradition, a closely related piece called simply "Lambang" dates from before the time of Sunjata, founder of the 13th-century Mali Empire, making it one of the oldest pieces in the repertoire, and one of several songs associated with Sunjata. In either version, it is a song to which jali women dance, stepping slowly, swinging their arms and tossing their heads back, as seen at the end of No. 5.

| [Opening donkilo line, sung in chorus] | Ye, jaliyaa, Allah l'e ka jaliyaa da. | Yes, jaliyaa, it was Allah who created jaliyaa. |

| [Masireng Kuyateh sings] | Ah, jali musolu ning jali kelu | Ah, jali women and jali men |

| [sung three times] | Lung be te jaliya ti | Not every day is a day for jaliyaa. |

| [spoken] | Bi le be dula. Tonya. | But today we are doing it. |

| Da le be mogolu lala bari mogolu mang kang. | People say that people are all on one level, but people are not the same. | |

| Ali n ga m fo nyo duniya, duniya la bambali. | We are here together in this world, but life is not everlasting. | |

| Kunung tambita, m be bi kono, sama be manso buru. | Yesterday has gone, we are here today, tomorrow is in the king's (God's) hand. | |

| Malaiko ke faniya fola a bada. | The angel of death never lies. | |

| Lung mang bo lung kang, kari mang bo kari kang. | One day does not overlay another, a new month does not emerge mid-month. | |

| Mansaya te mansaya kang. | One king's rule is not superimposed on his predecessor. | |

| Ni i ye mira duniya la, Saibolu tilo banta. | If you think about life, the sheik's days are over. | |

| Keme saba ning tan ning saba, wolu tilo banta. | Three hundred and thirteen (messengers of God), their times are over. | |

| Bulunding fula, sininding fula; mogolu bee mogonya sumayala. | Two small hands, two small feet; all people must help each other. | |

| [spoken] | Ali n ga m fo nyo duniyala. | We're here in this world together. |

| Ye, jaliyaa, Allah l'e ka jaliyaa da. | Yes, jaliyaa, it was Allah who created jaliyaa. | |

| Saibo Mamadu | Sheikh Mamadu | |

| Ye, jaliyaa, Allah l'e ka jaliyaa da. | Yes, jaliyaa, it was Allah who created jaliyaa. | |

| Gambia, ali nyo nane, Gambia; Gambia ali nyo muta kung, Gambia. | Gambia, let's all pull together; Gambia, let's all hold tight. [repeated] | |

| Suruwa ning Mandinko, Gambia | Wolofs and Mandinkas alike, Gambia | |

| Yamaruwo . . . | ||

| Ndaka Kuyate . . . | ||

| [Jali Sira Kuyate sings] | Yamaru-o, n ga nying fo nafa molu ma; nafa molu doyata. | Yamaru-o, I have sung this for the wealthy people; the wealthy are few. |

| Su kelu-o, su kelu-o, Musa Bala baba | The horsemen, the horsemen, Musa Molo's father | |

| M man la duniya la. | I don't trust this world. | |

| Nying Allah mu mansa nyimma ti. | This Allah is a beautiful King. | |

| Fatumata Fune ke aning Funeba, keme nani | Fatumata Fune's husband and Great Fune, [giver of] four hundred | |

| Ni i ye kuo meng sang, ngaralu wo le fo le koma. | If you thing which buy, singers this say after. [If you acquire fame, singers will talk about it after you are gone.] | |

| Ni i nata Serrekunda, sankumba ya. | If you come to Serrekunda, [it's] harvest time. [In Serrekunda, we are earning money today] | |

| [Standard praises for the Suso surname and leader of this group.] | Kiliya Musa ning Noya Musa, Nda be Sankumba la (?) | Kiliya Musa and Noya Musa, it's harvest time. |

| Ye, jalilya, Allah l'e ka jaliya da. | Yes, jaliya, it was Allah who created jaliya. | |

| [Denano Jawara sings] | Ye, yamaru-o, Tati ke, m b'e kumala. | Yamuru-o, Tati's husband, I am talking of you. |

| Su ka di keba do la, wula man di a la. | Home is sweet man one to, bush not sweet him to [One man does well at home and does not like to go away.] | |

| [Praise for generosity born of worldly knowledge through travel] | Wula ka di keba do la, su man di i la. | Bush is sweet man one to, home not sweet him to. [Another man excels abroad but is uncomfortable at home.] |

| [spoken] | A baraka | Thank you |

| Yiro san keme la, Allah ning Mama Dening Suma. | Buy the tree for a hundred [with the help of] Allah and Mama Dening Suma. | |

| Na kuyata mo meng na fo Yomali Kiyama ti. | One's difficulties, too, will be with one till death. | |

| [praise for Suso] | Bari eh, Alhaji Sankung sumayata; Sora Musa Bankalung. | But yes, Alhaji Sankung has died; Sora Musa Bankalung. |

| Eh, Madiba Bayo la Sankung, Jula Bayo, Jula Bayo | Eh, Madibo Bayo's Sankung, Trader Bayo | |

| Ye, jaliyaa, Allah l'e ka jaliyaa da. | Yes, jaliyaa, it was Allah who created jaliyaa. | |

| [Masireng Kuyateh sings] | Saibo Mamadu, tilo kili Mohamadu a baraka. | Saibo Mamadu, commander of the day Mohamadu, thank you. |

| Tilo kili Mamadu banta, karo kili ye manta. | Day-commander Mamadu is gone, the month-commander [Mamadu] has disappeared. | |

| Ah, lung bee te jaliyaa ti. | Ah, jaliyaa does not happen every day. | |

| Ni i be sembering molu la, i be sembering tumbu ning bakabaka. | If you rely on people, you are relying on worms and maggots. | |

| Hadamading mogo mu lung do ti. | "Adam's child" (a person) is a sometime thing. | |

| Ni nafulo si jongo bali sa la (?) | [meaning unclear] | |

| Ana Bilahi Suleyman | Messengers of Allah and the iron workers | |

| Wo ye duniya mara, bari a tilo banta. | They ruled the world, but their day is gone. | |

| (words unclear) | ||

| [praise names for the Suso surname] | Kiliya Musa, Nogoya Musa, Wanjaki Musa, duniya | |

| [Praise for Suntu Suso . . . son of Hamadi, and the hero ("Crocodile") of the day, for arranging the recording session.] | Hamadi Suso la Bamba, a baraka. | Hamadi Suso's "Crocodile," thank you! |

| Jali musolu ning jali kelu | Jali women and jali men | |

| Ali n ga baru ke duniya [unsaid: katu baru te Yomali Kiyama] | Let's put conversation in our life, [for there’s no conversation in the next world]. | |

| Mo ye meng ke duniya | Whatever you do in this life | |

| Hadamading mogolu be wo le fo le ye i ko. | Adam's children will talk of it after you are gone. | |

| Sora Musa a baraka; Jebateh muso la ke, a baraka. | Sora Musa, thank you; husband of Jebateh . . . thank you. |

Bangoura, Mohamed "Bangouraké." 2006. Mandeng Jeli.

(Yelidon)

From the Mandeng region.

This song is about the griot. We are so pround to be a griot, there is nothing better.

Diabate, Madou Sidiki. 2006. Traditional Kora Music from Mali. System Krush/Ascap, CD006.

(Lanban / Sandiya)

"Instead of being worried about how we start our lifetime, let's concern ourselves with how we will end our lifetimes." Lanban, or "end," is also known as Sandiya, (san:year, diya: happiness). This song, for its long history, has been played for all Djeliw, particularly to honor the old, present and passed.

Camara, Naby. 2010. Balaphone Instruction. Vol. 1. Earthtribe Percussion.

(Lamban)

Lamban was originally played on the balafon and kora od [sic] n'goni. These instruments that were exclusively played by the griots. [sic] Nowadays the rhythm is often played in the djembe ensemble.

Bangoura, M'Bemba. 2011. Wamato: Everybody Look! Featuring Master Drummer, M'bemba Bangoura. 2 vols. Wula Drum Inc.

(Lamba)

The rhythm Lamba is a rhythm from Guinea and Mali. Mostly in Guinea, we call it Lamba. If you go to Mali, they call it Djelido. Lamba is for the wedding. The traditional Lamba, they play just one djembe and three balaphones and one doun doun.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Djelidon)

The griot's dance from Burkina Faso.

see also:

Knight, Roderic, dir. 2010. Music of West Africa: The Mandinka and their Neighbors. Lyrichord Discs, LYRDV-2005.