mamaya

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Mamaya)

pp. 146–59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Mamaya |

| Translation: | Mama's place |

| Dedication: | Mama kaba |

| Notes: | |

| Calling in Life: | Folk hero, friend |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | L (after WWII) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

Konate, Famoudou. 1991. Rhythmen der Malinke. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

(Mamaya)

p. 65-6

Traditionnellement mamaya, tout comme la suivante diagba est une danse très lente, qui peut être organisée spontanément. A cet effet les femmes et les hommes se placent sur une ligne et dansent toujours sur les mêmes pas. A l'origine il n'y avait pour ce rythme aucun échauffement. Aujourd'hui ces rythmes sont aussi joués lors des mariages et des fêtes semblables, mais à un tempo plus rapide.

Rythme: cycle de 24 pulsations, subdivisé en 2 groupes de 12.

Paroles de la chanson:

Mon frère, tu es galant,

ça me plait beaucoup.

Même les griottes chantent partout

combien tu es galant!

Kouyate, (El Hadj) Djeli Sory. 1992. Guinée: Anthologie du balafon mandingue. Vols 2 & 3. Buda, 92534-2, 92535-2.

(Mamaya)

A very popular tune from the Guinean Highlands, which Soufiana Kouyate introduced in the coastal region in 1939.

Kaba, Mamadi. 1995. Anthologie de chants mandingues (Côte d'Ivoire, Guinée, Mali). Paris: Harmattan.

(Mamaya / Bandian Sidime)

pp. 7-9

Parmi les chants mandingues reconnaissable par leur rythme, on peut citer entre autres : . . . les mamaya dansés depuis 1938 à Kankan en Haute Guinée et qui prennent leur source dans le "bada" malien.

p. 187

BANDIAN SIDIME1

Oh ! Vieux sages de Salamanida,

Bénissons tous sincèrement Bandian

Car Dieu seul peut le récompenser.

Le donateur de fortune de Salamanida s'est couché.

Oh ! Bandian, donateur de fortunes

Quand tu n'offrais pas toute une fortune,

Tu en offrais au moins la moitié !

En ma présence,

tu as été désigné parrain,

Au mois d'attente de celui du Ramadan.

La mort peut toujours emporter un homme,

Mais elle ne peut emporter son bon renom.

Oh ! Bandian, le fils béni de sa mère,

Le célèbre ivoirier bien-aimé

M'a laissé tout seul ici-bas

Et s'en est allé dans l'au-delà

Où il danse encore la mamaya.

1 Bandian, jeune culpteur émérite d'ivoire aimé des jeunes et des griots, fut terrassé par la mort vers 1947.Les griots et les jeunes l'ont pleuré et lui ont dédié ce chant qui fut repris presque dans tout le Manding. La mamaya est une danse collective qui eut beaucoup de succès en 1947. Salamanida est un quartier de Kankan en Guinée. Ce morceau a été enregistré sur disque par la chanteuse malienne Oumou Dioubaté.

p. 214

LE GENDARME1

(SANDARAMA KE)

Je me suis laissé prendre

Par le méchant gendarme.

Mes yeux sont bouffis de sommeil,

Je ne me contrôle plus.

J'ai cherché en vain des hommes influents,

Pour intervenir en ma faveur,

Et je souffre énormément.

Oh, je me suis fait prendre

Par le méchant gendarme.

1 Pendant la dernière guerre mondiale, alors que sévissaient les travaux forcés, les livraisons obligatoires de céréales et les arrestations des contrebandiers circulant entre les colonies françaises et anglaises, il fut créé un corps de gendarmes à pied ou à cheval et qui étaient chaussés de bottes avec guêtres remontant jusqu'aux genoux. C'étaient des agents de répression particulièrement craints des populations. Il s'agit d'un chant du rhythme "mamaya", cette danse qui était en vogue en Guinée, en 1942, date à laquelle les commerçantes de Kankan jouissaient d'une certaine prospérité mais étaient en butte aux tracasseries des douaniers et des gendarmes.

Keita, Mamady. 1995. Mögöbalu. Fonti Musicali, FMD 205.

(Mamayah)

An old Mandingo dance, Mamayah was particularly popular in the 1940s and 50s. It was brought back into fashion by celebrities of the period such as Bandian Sidimé, Sidi Karamö Diabaté, Karamo Kaba, Mary Kéra (whose name is mentioned below), and Namoudou Kondé. Dressed in goubas (large amply cut shirt-like outer garments) and embroidered shirts, the dancers split into two concentric circles, the women's circle within the men's circle. They perform the steps of the dance in a majestic fashion, here waving a white handkerchief, there a decorated staff.

| Nymah, Sayah, Sayah tè djon too lah, | Living or dead, Death bears all slaves away. |

| djouwa ma sinin lon, | A madman cannot know what will happen on the morrow. |

| n'na-dönèn Djidaba Condè möyida | My stepmother has given birth. |

| tolon tè söbè salah, | We are as unbeatable in amusing ourselves as we are in being serious. |

| Djémory lanèn Commissariat. | Djémory spent the night at the police station. |

| Saninti mako, | Whoever has gold wants more of it. |

| wöditi mako lé, | Whoever has money wants more of it. |

| djonthiè kouroubati lé, | Whoever has slaves wants more of them. |

| Lahila ilanlaha Mohamadi Rassoulou Allahi, | There is no God except for Allah and Mohamed Rassoulou his prophet. |

| ikana n'mida mökan né la, Karamö Kaba, ika n'mida mökan né lah, N'Fa wo Famah Dén. | Pay no attention to what they say about me, o Prince my father! |

| Mamayah wo djély mina djélity lah, | In the Mamayah, consider the griot in relation to his master: |

| Mamayah djéli koron né djélyah tignèn na. | In the Mamayah, it's the bad griot who spoils the art of the griots. |

| Mamayah wo finah mina finati lah, | In the Mamayah, consider the finah* in relation to the master of the finah: |

| Mamayah finah koron né finayah tignèn na. | In the Mamayah, it's the bad finah who spoils the art of the finah. |

| Mamayah, wo, n'né ma lawouly wo ma. | Oh Mamayah, it was not for this that I undertook this voyage. |

| Mandén djaly la Saralon ta, | It was not worth the trouble of going to Sierra Leone, |

| N'ni wa mökén soo. | I will go to the village of the handsome men. |

| Mamayah wo, Mamayah wo, hina yé dari lé dö, kininkininko | O Mamayah, those who live together know what pity is. |

| Sandia nada brouilli lé di, sandia bah namöyida. | A pitiable thing, Sandia has sent forth noise, the great Sandia. |

| Mary Kéra wo, Mary Kéra wo, ina möyi da dénthiè lah! | Your mother has given birth to a boy. Oh Mary Kéra, oh Mary Kéra (...) |

| (...) Eéé djélyi yé wolé föla dougna yéé! | If this is what the griots tell the world (...) |

| (...) Massömah n'téry... N'téry... | My friend, see you soon, my friend... |

* a particular age-group in the 1950s from Kankan who created the Mamayah's renown [sic].

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Mamaya)

Traditional Ethnic Group: Malinke; Northeast Guinea

Mamaya is a rhythm that accompanies an elegant dance which shows off the beauty of the male and female dancers.

This dance is performed within an association or a club to which both men and women belong. This association calls itself "Ton" or "Sede." The president of the club is called "Sedekunti."

The members of the club support each other and help each other financially, too, for instance, in the organization of a big wedding.

To become a member of such a club, one has to request a meeting with the Sedekunti in his office, and bring ten cola nuts as a small token of appreciation.

For organizing a Mamaya, many helpers are needed. All of the club's members (that could be up to one hundred) have to be invited and informed, for instance, if a certain dress color is prescribed for this celebration. This kind of festivity only happens in bigger villages.

The rhythm is set by the songs of the griots, as well as the bala, the tama, and the bölön.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Mamaya)

p. 148

pp. 152–53

The bala-based piece Mamaya, created by Dioubate (Diabate) jelis in Kankan in the 1930s or 1940s, perhaps in collaboration with Kante jelis from the area, appears to be inspired by Lamban, not so much in its musical content but as a celebratory piece by and for jelis (and their nonjeli age-mates) with a distinctive dance associated with it. The same Lamban three-stroke dundun pattern can also be played for Mamaya.83

83. See . . . chapter 5 and Kaba and Charry (forthcoming) for more on Mamaya.

p. 183

114. . . . Also see the discussion of Mamaya, which probaby is based in Konkoba performances, in chapter 5.

p. 198

With a few exceptions, such as hunters dancing to sounds of their harps and the dance pieces Lamban and Mamaya played on the bala, drums are the instruments of choice for dancing.

p. 250

Older pieces from the jeli's repertory were rare on commercial recordings before the 1960s.13 Among the several twentieth-century jeli pieces recorded were Kaira, Yarabi (Diarabi), and Mamaya (also known as Bandian Sidime), all three recorded by both "Soba" Manfila Kante (1961?-disc) and Nouhoum Djallo (Nourrit and Pruitt 1978, 1:49–50).

pp. 286–87

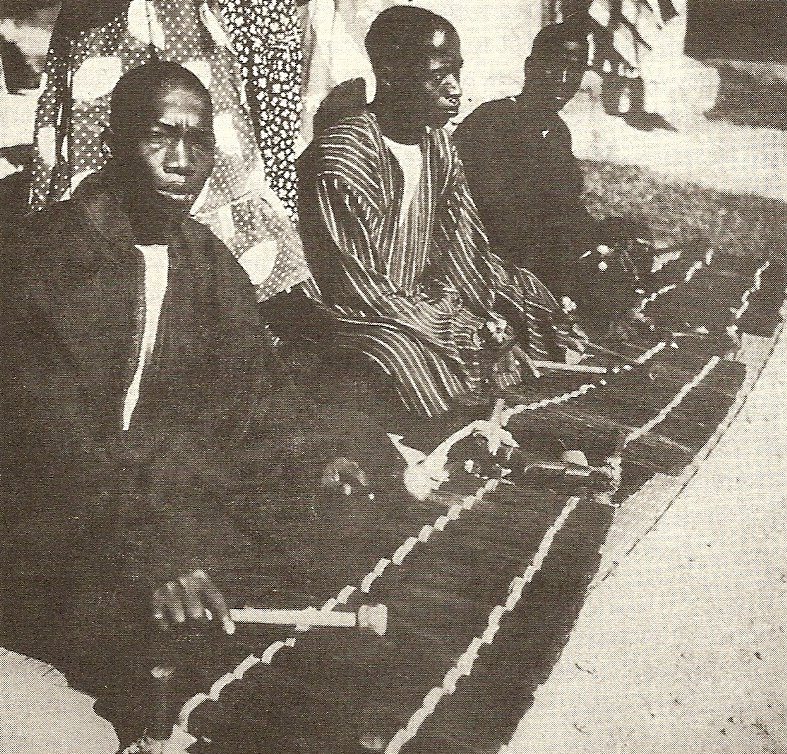

Most of the twentieth-century pieces that have entered the repertories of jelis and orchestras come from upper Guinea. Mamaya, a social event that arose among youth in Kankan sometime in the 1930s, deserves special notice (Kaba and Charry, forthcoming). Although the actual event, which includes slow group dancing in a circ1e, fell out of favor by the 1960s, it continues to provide musical inspiration for Guinean musicians. The music of Mamaya comes from the bala, and it originated among the bala-playing family of Sidi Dioubate and the virtuoso bala ensemble of his sons Sidi Mamadi, Sidi Karamon, and Sidi Moussa (plate 48).

Plate 48 Dioubate Brothers of Kankan, 1952. From Rouget and Schwarz (1969, facing 48).

The reverence in which these musicians were, and still are, held and the continued interest in this piece make Mamaya an extraordinary phenomenon in the history of Mande music. The documentation of Mamaya may begin as early as the early 1930s with silent film shot by American anthropologist Laura Boulton (1934-vid). Part of the film shows a Konkoba celebration, named for a large masked figure local to Upper Guinea, with musical accompaniment by an elderly man with three young men all playing balas, probably a father and his sons. Boulton recorded a tape concurrently, and the music is reminiscent of Mamaya. Although unidentified, the musicians might be from either a famous jeli family from Siguiri known as the Konkoba Kouyates or the Dioubate creators of Mamaya from Kankan.44 Alberts (1949-disc, 1998-disc) made recordings in Kankan in 1949, and the bala players and singers, identified by Alberts as being recorded at Sidi Djelli (the name of the family patriarch), are certainly the Kankan Dioubate family performing Mamaya. Rouget (1954a-disc, 1954b-disc) recorded the Dioubate brothers in Kankan in 1952 and published an article on bala tuning based on measurements he made of their three balas (Rouget and Schwarz 1969).45 Recent recordings associated with Mamaya are revealing of change and renewal in Maninka music. Oumou Dioubate (1992?-disc), daughter of Mamaya cocreator Sidi Mamadi Dioubate, pays homage to her grandfather Sidi Dioubate in Sididou (Sidi's place) by systematically naming the children and grandchildren, thereby praising Sidi for his progeny. An extended sung genealogy like this in a modern music setting is uncommon (especially when one's own family is concerned), but Sidi Dioubate's heroic status as Mamaya creator merits this special treatment. Oumou's older sister Nakande Diabate (daughter of Sidi Mamadi and Namama) has recently recorded a version of Mamaya with jembe player Mamady Keita (1995-disc), with lyrics all but identical to the version recorded by Alberts forty-five years earlier. Another version of Mamaya by Baba Djan Kaba (1992-disc), titled Kankan after the town that gave birth to Mamaya, is extraordinary on several accounts. Baba Djan belongs to the aristocratic ruling Kaba lineage, also known as Maninka Mori, known for its Islamic scholarship and theocratic rule; the family had no previous association with music making. Kaba's singing therefore is not bound by the jeli's aesthetic of praise, much as the female Wasulu singers are free to comment on contemporary matters in Mali. Kaba's musical sensibility is a fascinating mix of the Kankan jeli tradition freed of the Cuban-influenced, brass-dominated orchestras of the immediate postindependence period of the 1960s and 1970s. In Kaba's hands the bala-based Mamaya is transformed into a powerful orchestra of 1990s Guinea featuring one bala, one kora, three electric guitars, a jembe, electric bass, synthesizer, drum machine, and female chorus.

44. A few musicians have identified the Boulton (1957-disc) bala recording for me as Mamaya but they may be referring to the music in general rather than the specific piece being played. The piece follows the harmonic scheme of Nanfulen (and also Fakoli), a rare form having three harmonic areas of equal duration rather than the usual two or four. This same form, but with a subtle difference in one of the harmonies, is transcribed as a Konkoba bala piece by Joyeux (1924: 208), who would have witnessed it in Kankan, the very heartland of both Konkoba and Mamaya. Perhaps Konkoba was one of the main sources of inspiration for the young generation of the 1930s that created Mamaya. See M. Kaba (1995: 187) for a song dedicated to Bandian Sidime, a noted Mamaya personality.

45. Although Boulton's film is cataloged as being shot in Bamako and Bankumana, Mali, several African viewers believe that parts of it may have been shot in Guinea. The Kankan musicians playing on the Alberts (1949-disc) recordings were easily identified during my 1994 trip to Conakry. Ntenen Janka Saran, younger sister of the bala-playing Dioubate brothers and aunt of my host Kabine Kante, made the most moving identification, recalling that she was one of the young girls singing on the tape (see Alberts 1998-disc for a photo of the female chorus; Rouget 1999-disc has a photo of the bala players and their wives). Hearing old recordings is not a common experience for many Africans, and she broke down in tears on hearing her long departed family members, just as her nephew had predicted.

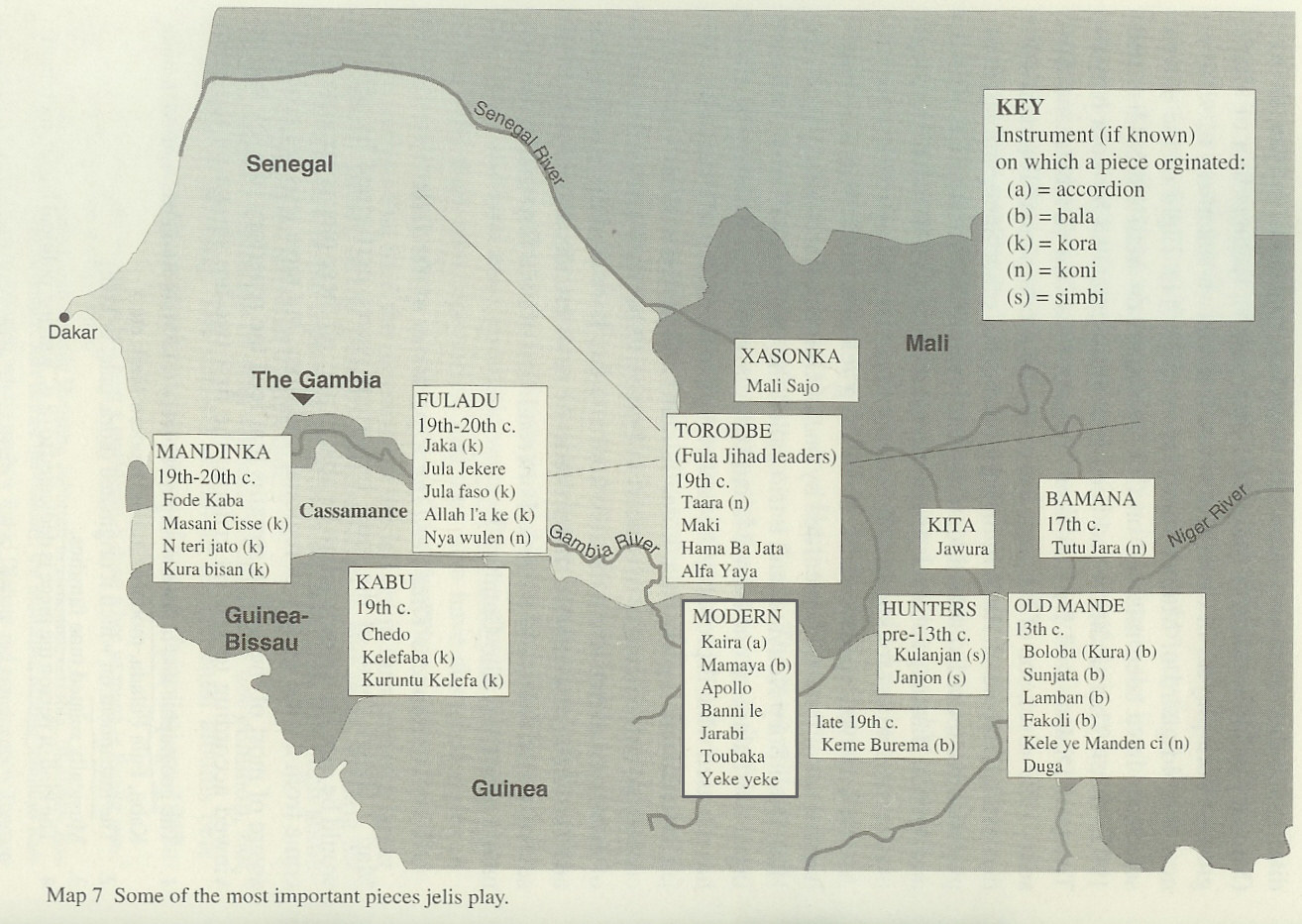

pp. 398–401 (Appendix C: Recordings of Traditional and Modern Pieces in Mande Repertories)

Modern: Mamaya

Arthur Alberts (1949)

Keletigui et Ses Tambourinis (1967b)

"Soba" Manfila Kante (1961?, vol. 8)

The Ivorys (1987)

Jali Musa Jawara (1988)

Ami Koita (1992)

El Hadj Djeli Sory Kouyate (1992, vols. 2 and 3)

Djimo Kouyate (1992a)

Nahini Diabate (1998)

Mamady Keita (1995)

Keletigui Diabate (1996)

Ba Cissoko. 2003. Sabolan. Marabi.

(Mamaya)

A traditional ballad from the Mandingo saga, where the kora guides women at important festivities.

Keita, Mamady. 2004. Guinée: Les rythmes du Mandeng. Vol. 2. Fonti Musicali, FMU 0320.

(Mamaya)

Mamaya was for the Malinke people a dance for the griot cast in the regions of Siguiri and Kouroussa. Mamaya became very popular as it is a very elegant dance which really highlights the skill of the dancers. It is only danced and played at certain very grand festivals which are specially organized.*

* Transcription mine; of English-language DVD narration.

Conrad, David C. 2010. "Bold Research During Troubled Times in Guinea: The Story of the Djibril Tamsir Niane Tape Archive." History in Africa 37: 355-78.

(Mamaya)

pp. 375-6

Documentation of the music or "social event" known as "Mamaya" began in the 1930s. Enormously popular through the ensuing decades, Mamaya has been described by Eric Charry as "[…] an extraordinary phenomenon in the history of Mande music."58 The influence of Mamaya remains strong in Mande music,59 and the reels in the Niane archive labeled Mamaya de Kankan should contribute significantly to the discography of that genre for the 1960s. When one of the great Mamaya groups from Kankan visited Conakry during the first decade of Guinean independence, Niane recorded their performances.60 In one of our conversations, Niane vividly characterized the early days of Mamaya in northeastern Guinea as a time of burgeoning prosperity and unforgettable women. He described the 1930s in Kankan as a "belle époque" with the town full of wealthy "commercants," flourishing gold mines of Siguiri to the north, and great amounts of kola nuts flowing into Kankan from Kissidougou, Beyla, and N'Zerekore in the forests to the south. The first big transport trucks into Kankan were rendering animal caravans obsolete, bicycles were replacing horses, and the arrival of the railroad with trains from the port of Conakry brought the town to its peak as a crossroads for trade. Evoking names like "T. Bèb" and "Djomatiné" as women of the time memorable for their beauty, Niane recalls that in Siguiri the most beautiful girl was Musogbé, and that a second Mamaya group arose in that town to compete with the one in Kankan. Meanwhile, Kankan's Mamaya music praised a famously beautiful eighteen-year-old girl named Ténéngbé Condé who traveled and danced with that city's troupe.61

59Charry, Mande Music, 286-88; see also Lansiné Kaba, and Eric Charry, "Mamaya: Renewal and Tradition in Maninka Music of Kankan, Guinea (1935-45)" in: Ingrid Monson (ed.), The African Diaspora: A Musical Perspective (New York, 2000), 187-206; David C. Conrad, Somono Bala of the Upper Niger: River People, Charismatic Bards, and Mischievous Music in a West African Culture (Leiden/ Boston/Köln, 2002), 35-36.

60Niane says the troupe remained in Conakry for about a month, and he remembers two of the musicians, Djelikaba Koudouni playing nkoni and Sinimori Kouyaté playing the balafon. He has forgotten the names of two young women with them who performed the Mamaya vocals and regrets that when he was recording them he did not think to take a picture.

61My translation from Niane's French.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Mamayah)

Malinke rhythm from Upper Guinea played for members of an association.

Dioubate, Famoro. 2014. Kontendemi. Self-produced.

(Mamaya)

We have a lot of melodies in mamaya, but the first one the jeli people know, from Kankan, is this one.

Transcription mine. (Adapted.)

see also:

Kaba, Lansiné & Eric Charry. 2000. "Mamaya: Renewal and Tradition in Maninnka Music of Kankan, Guinea (1935-1945)." In The African Diaspora: A Musical Perspective, ed. Ingrid Monson, 187–206. Florence, KY, USA: Routledge.