sunjata

Diabate, Massa Makan. 1970. Janjon, et autres chants populaires du Mali. Paris: Présence Africaine.

(Sun Jata Faasa)

pp. 19–42

Une mère chante son fils

Lors des naissances, des circoncisions et des mariages, vous entendrez dans nos villages et dans nos villes ces chansons bien vieilles et toujours jeunes, car elles chantent la femme, la mère, l'orgueil du genre humain.

Les traditionalistes les attribuent à Sogolon Kutuma Konte, la mère de Sun Jata.

La nature n'avait pas épargné Sogolon. Elle l'avait accablée de bosses. Et la maternité n'était pas venue à son secours. Elle avait mis au monde un paralytique.

Un jour ce garçon qui faisait le désespoir de sa mère se dressa pour s'inscrire dans notre histoire.

Ce jour-là, en chantant son fils, Sogolon Kutuma de la famille des Konte ne chantait que la maternité, espérance de toute femme.

« Voyez la belle stature de mon fils !

De la petite graine est sorti un fromager.

Aujourd'hui femmes du Mande,

Nare Magan Konate s'est levé ! »

— Magan Konate, il va falloir que tu te lèves, dit la mère. Pour t'apprêter ton plat favori, le fonio aux feuilles de baobab, j'ai supplié toutes les voisines. Et toutes m'ont répondu : « N'as-tu pas honte, Sogolon? Tu as un fils ; dis-lui de grimper à l'arbre. »

— Mais je suis perclus, mère !

— Elles ne l'ignorent pas, Magan Ronaté, répondit Sogolon en pleurant.

— Tes larmes me sont douloureuses, mère; va dire à Sorijan Rante, le forgeron, de fabriquer une barre de fer . Je vais me lever, mère ; et à compter de ce jour, toutes les femmes de Kikoroni viendront chercher leur provision de feuilles de baobab devant ton enclos.

Et Sogolon Konte s'en alla à la forge, pleine d'espoir comme un aveugle anquel on a promis la vue.

Sorijan Kanté fit vite. Mais quand Magan Konate saisit la barre de fer, elle se courba.

— Mon espoir envolé, je n'ai d'autre recours que toi, O Dieu du ciel, gémit la mère. Je suis Sogolon de la famille des Konte. Je m'en vais donner une branche de Jonba à mon fils. Moi, Sogolon Konte, j'affirme qu'au monde, je n'ai connu d'autre homme que Nare Fatta Kegni, mon mari. Je dis que ma bouche n'a jamais proféré un mensonge. L'orphelin m'a souvent dit merci pour le secours de mon bras, et la chaleur maternelle que j'apporte à tout enfant. Et si ce n'est assez de ce serment, à ta face, O Dieu du ciel, je clame ma pureté. La vertu est récompensée, dit-on. Aussi, Dieu du Ciel, donne à mon fils la vigueur de ses jambes. Elle tendit la branche de Jonba à Magan Konate ; il la prit et se leva sans effort aucun.

« Le Bonheur est là

Chanta la mère.

Il est venu le bonheur,

Le Bonheur triomphe chez moi! »

Accroupie au sol, elle pleurait :

« Voyez la belle stature de mon fils ;

De la petite graine est sorti un fromager.

Aujourd'hui, femmes du Mande

Nare Magan Konate s'est levé. »

Elle se coucha, prise de vertige. Et elle tremblait, tant était grande sa joie:

« Notre vestibule est un vestibule de bonheur.

Un bonheur ne passe jamais

Sans entrer chez nous.

Aujourd'hui, femmes du Mande,

Nare Magan Konate s'est levé. »

C'est avec peine qu'on entendit ses paroles quand elle chanta :

« O vous coépouses jalouses !

Pour moi ce jour est faste;

Le Dieu du ciel n'a jamais rait

Un jour plus beau.

Aujourd'hui, coépouses jalouses,

Nare Magan Konate s'est levé ! »

Couchée au pied de son fils, elle vit comme en un rêve toutes les misères affrontées, les railleries et l'humiliation :

« Toi qui souffres,

Ne mets pas fin à tes jours

Pour échapper à la misère.

Pourquoi se tuer pour avoir souffert?

Sait-on jamais ce qui succède à la misère? »

« Regarde, aujourd'hui

Nare Magan Konate s'est levé. »

Elle leva les yeux sur son fils debout comme un dieu de majesté, impatient de marcher. Elle s'accrocha à ses jambes :

« Pas encore, dit-elle... Beauté de la race ! Regardez comme ma race est belle ! »

Elle lâcha prise, ferma les yeux et roula loin de Nare Magan Konate pour mieux le voir :

« Toi qui as mis

Au monde, un bel enfant,

Tu n'auras pas honte

Les jours de fête. »

Bientôt elle voulut que chacun partageât sa joie :

« Sortez

O vous femmes du Mande!

Sortez!

Un spectacle est à voir. »

Et quand l'on forma un cercle autour d'elle,

« Vous êtes venues femmes!

Mais avez-vous apporté avec vous

Un spectacle qui vaut le mien?

— Maintenant, dit-elle en montrant son fils du doigt, veux-tu marcher vers le plus grand des baobabs. Il est à Kakama dans le champ de ton père. »

Le fils de Sogolon s'avança lentement; ensuite il précipita le pas comme un guerrier qui affronte un obstacle. Et c'est avec peine que sa mère put s'attacher à ses pas :

« Champ de roseaux

Tu ne l'arrêteras pas!

Femmes du Mande,

Non, Sun Jata ne s'arrêtera qu'à la forêt. »

— Oublions notre jalousie mes soeurs, dit une femme. Sogolon Konte a souffert. Mais aujourd'hui n'a-t-elle pas montré que la vertu triomphe de la misère? Reprenons en choeur sa chanson.

Sogolon de la famille des Konte se retourna, et la fatigue, et la joie et les larmes donnaient à son visage une expression singulière. On pouvait y lire l'oubli à la recherche du pardon :

« O vous toutes !

Vous qui me suivez,

Jugez-moi par le bruit de mon pas.

Seul résonne le pas

De celui qui est suivi

o vous toutes !

Vous qui me suivez,

Suivez-moi donc.

Car le vent emporte le solitaire. »

Arrivé au baobab, Sun Jata le secoua, l'arracha et vint le jeter devant le jasa de sa mère. — Je l'avais dit, s'exclama-t-il — Désormais toutes les femmes viendront s'approvisionner auprès de toi.

« Ordure ! Ordure ! Ordure !

Tout se cache sous l'ordure

Et l'ordure sous rien.

Tout se cache sous l'ordure;

Mais pas le feu ! »

Et à l'intention des femmes éperdues d'épouvante, elle dit :

« Eau de mare

Ne te compare à l'eau de roche.

Pure est la source ! »

Ensuite elle se mit à danser.

« Battez des mains pour moi

O vous femmes !

Ne savez-vous pas combien j'ai souffert ?

Aujourd'hui femmes,

Nare Magan Konate s'est levé. »

Elle se dirigea vers son fils, massa ses jambes avant de dire :

« L'insensé s'attache à l'instant ;

Il ne voit pas l'avenir.

L'insensé est tout à l'instant ;

Il n'a aucune ouverture sur l'avenir. »

Un rire diabolique explosa de ses lèvres, elle se plut à le répandre en cascades

« La grêle va tomber,

Mettez-vous à l'abri, femmes !

Quand la grêle tombe,

On se met à l'abri.

Insensé ! ne reconnaîtrais-tu pas,

Au premier coup d'oeil,

Celui qui en force t'est supérieur ?

Aujourd'hui, femmes,

Nare Magan Konate s'est levé. »

Elle vint au baobab déposé devant son jasa et lui arracha quelques feuilles.

— Longtemps, dit-elle, j'ai fermé l'oreille aux railleries. Pour l'avoir longtemps fermée, on m'accusait d'effronterie. Mais aujourd'hui, femmes, Nare Magan Konate s'est levé.

Et montrant son fils du doigt :

« Aucun coq ne peut

Se mesurer à toi

O coq de trois ans !

Qu'aucun coq ne se' mesure à toi ! »

Epuisée, elle s'accrocha au cou de Sun Jata en le regardant dans les yeux :

« Tu es l'initié

Qui n'a pas eu peur du fer.

Ta place est dans la foule.

Tu es l'initié

Qui a affronté le fer sans ciller,

Ta place est au combat. »

Sun Jata Fasa

Les traditionalistes (1) attribuent généralement le refrain de cette chanson à Tumu Manian, une vieille griote qui aurait suivi Sun Jata en exil ; tandis que les couplets auraient été improvisés par Bala Faseke Kuyate après la victoire de Sun Jata sur Sumangurun.

Le Sun Jata Faasa est un véritable syncrétisme. Il n'oublie rien, ni personne : les aïeux de Sun Jata, leurs compagnons d'armes, les compagnons de Sun Jata et ses ennemis, l'origine du Mande, tout est évoqué.

Cette chanson, si elle est féodale, a le mérite de situer Sun Jata par rapport all passé tout en s'ouvrant sur l'avenir :

« Si d'autres t'ont devancé, si d'autres encore doivent venir après toi, tu te dois d'epuiser le champ d'action qui t'est donné » (2).

« Les gens de Soso et ceux de Mande

En sont venus aux armes.

Les larmes s'en sont allées au pays de Soso,

Les rires ont perlé au Mande... »

(1) Les traditionalistes, et pour n'en retenir que quelques-uns, Tiémoko Koné à Mourdiah, Yamourou Diabaté à Kela, Kele Monson Diabaté à Karaya (cercle de Kita) et Fadigui Sissoko à Bandoma s'accordent pour attribuer le refrain du Sun Jata à Tumu Manian, et les couplets à Bala Faseke Kuyate. Cependant Djibril T. Niane à partir d'autres sources pense que le refrain du Sun Jata a été lui aussi improvisé par Bala Faseke Kuyate, le griot de Sun Jata.

(2) Pindare, cité par M. Verret in [sic] Les Marxistes et la Religion, Editions Sociales.

Sogolon Magan, Oh fils de Sogolon !

Tu es né pour que les maîtres de la parole

Te glorifient au Mande;

Mais sache-le, Sogolon Magan

D'autres t'ont précédé au Mande

Et d'autres encore te succéderont.

Aussi rendons hommage à Sumangurun

Qui se rendit maître du Soso.

Sumangurun, le premier

Des rois de chez nous.

Prenez vos carquois, gens du Mande !

Prenez vos arcs, gens du Mande !

Sogolon J ata est né pour être roi.

Oui, gens du Mande !

Sun Jata ne pouvait qu'être roi.

Saluons donc Sumangurun

Qui se rendit maître du Soso.

Sumangurun, le premier

Des rois de chez nous.

Les gens de Soso et ceux de Mande

En sont venus aux armes.

Les larmes s'en sont allées au pays de Soso,

Les rires ont perlé au Mande.

Saluons donc Sumangurun,

Le premier des rois de chez nous.

Il a pris son arc, le grand chasseur.

Le grand chasseur a pris son arc

Pour affronter la savane.

Sogolon Magan a pris son arc !

Il a pris son arc,

Kirifiya Magan Konate a pris son arc

Pour s'en aller chasser.

Il a pris son arc, Sinbon !

Sinbon a pris son arc

Pour affronter la savane.

Il a pris son arc,

Le grand chef meneur d'hommes !

Il a pris son arc,

Le grand chasseur qui passe

Les grands fleuves !

Il a pris son arc pour affronter la savane.

Il prend le pays à son roi

Tout en chassant.

Le sable à son propriétaire,

Tout en chassant.

Il assomme les orgueilleux

Tout en chassant.

Il a pris son arc, Sinbon !

Sinbon a pris son arc

Pour affronter la savane.

Cette chanson, on l'a chantée

Pour des hommes de premier rang au Mande.

On l'a chantée pour Nyani Masa Kara

A Nyani Kurula.

Pour Sibi Ngunafaran Kamara

Et pour Tabunguafaran Kamara.

Elle a célébré Kolinkin Magasuba

Fils du grand féticheur Magasuba Dan'na

Et ils n'étaient ni sorciers ni génies...

L'ange de la mort même

A souillé sur le Mande.

Tu vois, Nare Magan Konate

Tu as été précédé.

Les hommes passent,

Les hommes se succèdent depuis toujours...

Oui, Sogolon Magan le pouvoir est une jouissance.

Kiriftya Magan Konate la jouissance est dans le pouvoir.

Tu as fait la guerre

Et le plus fort a triomphé.

Les gens de Soso et ceux de Mande

En sont venus aux armes.

Les larmes s'en sont allées au pays de Soso.

Et les rires ont perlé au Mande.

Tout le Mande a commencé

Par Damansawulenba et Wulentanba.

Sibi avait engendré Kenbu ;

Et Kenbu, Kenbu Tenin et Mulayi Tarawele.

Mais arrêtons ! s'il faut toujours s'arrêter...

Où sont-ils aujourd'hui?

Tu vois, N are Magan Konate

Tu as été précédé.

Les hommes passent, les hommes se succèdent.

Tu es le roi de l'arrière-pays

Car Tira Magan a passé le fleuve.

Oh Nare Magan Konate, le pouvoir est une jouissance.

Mais d'autres t'ont précédé

Et d'autres encore te succéderont.

L'ange de la mort même

A souillé sur le Mande...

Il est venu un homme

Du nom de Tanan Mansa Konkon.

Si le tas d'ordures se décompose toujours,

Si son odeur ne tue pas,

Elle fait vomir.

Oh Sinbon ! en toute liberté

Tout le Mande a combattu

Pour ton aïeul à Dagayala.

Mais dis-moi, Sinbon

Où sont les hommes d'autrefois?

Il est venu un homme

Du nom de Sunu Sako, Sunu Mamuru.

Un autre, et il avait nom Sogona Magasi.

Ils ont combattu pour ton aïeul à Dagayala.

Pour Julu Kara Nayini

On jouait une trompette

Taillée dans un os humain.

On jouait pour Julu Kara Nayini

Une trompette d'or.

Sinbon, où sont les hommes d'autrefois?

Au Mande naquirent Kukuba et Bantanba.

Nyani Nyani Kanba Siga naquit

Lui aussi pour le Mande.

Mais arrêtons ! s'il faut toujours s'arrêter...

Sumangurun est entré au Mande

Avec une coiffure en peau d'homme,

Un « kurusi » en peau d'homme,

Un boubou en peau d'homme.

Et tous les braves ont combattu

En toute liberté. Oh Sinbon,

Où sont-ils maintenant ?

Fakoli-à-la-gros-se-tê-te !

Fakoli-à-Ia-gran-de-bou-che .!

Il se promenait au Mande

Avec trente-trois têtes d'oiseaux

Accrochées à son bonnet.

Fakoli-à-la-gros-se-tê-te !

Fakoli-à-la-gran-de-bou-che !

Il est entré au Mande

Avec trente-trois peaux de lion.

Et il n'était ni sorcier ni génie.

O Sinbon ! où sont les hommes d'autrefois ?

Tu vois, d'autres t'ont précédé

Et d'autres te succéderont.

Il a pris son arc, le grand chasseur.

Le grand chasseur a pris son arc

Pour affronter la savane.

Sogolon Magan a pris son arc !

Il a pris son arc,

Kirifiya Magan Konate a pris son arc

Pour s'en aller chasser.

Il a pris son arc, Sinbon !

Sinbon a pris son arc

Pour affronter la savane.

Il a pris son arc,

Le grand chef meneur d'hommes !

Il a pris son arc,

Le grand chasseur qui passe

Les grands fleuves !

Il a pris son arc pour affronter la savane.

Il prend le pays à son roi

Tout en chassant.

Le sable à son propriétaire,

Tout en chassant.

Il assomme les orgueilleux,

Tout en chassant.

Il a pris son arc, Sinbon !

Sinbon a pris son arc

Pour affronter la savane.

Chants à la mémoire de Sun Jata

— Oui, retournons à la terre ! Le Mande a commencé par la culture ...

En effet, le premier village du Mande s'appelait Ki, disent les traditionalistes. C'est-à-dire le travail, travail de la terre s'entend.

Les trois Sinbon, Kanu Sinbon, Kanunyongon Sinbon et Lawali Sinbon, tous trois petits-fils de Bilal, l'esclave du Prophète, étaient venus au Mande, portant chacun une caisse, don de l'aïeul. Après avoir pris connaissance du contenu de leur fardeau, ils se querellèrent.

Kanu Sinbon, l'aîné, avait de l'or dans la sienne; Kanunyongon Sinbon, de l'écorce d'arbre et le plus jeune, Lawali Sinbon, de la terre.

Les deux cadets demandèrent le partage de l'or.

— Mettons tout en commun, dit l'aîné. Le partage nous affaiblirait.

Loin de tirer profit de ce sage conseil, Kanunyongon Sinbon et Lawali Sinbon portèrent le litige devant Kabaku, le roi d'un pays qu'on appelait l'Etrange.

— La terre vaut l'or, dit Kabaku. Et l'écorce des arbres vaut la terre. Mais le travail est supérieur aux trois réunis.

Ainsi réconciliés, les trois Sinbon fondèrent le village de Ki (travail).

Le Mande a donc commencé par le travail, le travail des champs.

Mais les hommes se succèdent depuis toujours... Il naquit pour le Mande « un chasseur forcené, un conquérant irréductible ». Il avait nom Sun Jata .

Il agrandira le Mande par la conquête, et la chasse ne sera plus une source suffisante de revenus.

Dans cette chanson Sun Jata apparaît comme le symbole de la sédentarisation nécessaire des hommes du Mande par la culture et le commerce.

— Oui, retournons à la terre — Rien ne vaut la culture. Le Mande a commencé par la culture, le Mande reviendra à la culture...

«Il cultivera celui qui

Aura choisi la culture,

Et rien que la culture.

Sun Jata n'est plus.

Il s'adonnera au commerce celui qui

Aura choisi le commerce,

Et rien que le commerce.

Suba a vécu. »

Nare Magan Konate est mort dans le pays qu'arrose le Sankarani. Là on vous dira qu'il repose à Balandugu. Les gens de Balandugu vous enverront à Duguba, et ceux de Duguba encore plus loin à Bakunku.

En vérité Sun Jata repose dans la forêt de Nora... Tous les hommes du Mande se sont groupés auprès de sa tombe. Il y avait là les trente familles horon, les quatre familles Nyamakala et la famille de ceux qui suivent les autres.

Mais qu'allons-nous faire maintenant que Suba est mort ? Qu'allons-nous faire au Mande ? Qu'allons-nous faire du Mande ?

Et tandis que chacun se posait ces graves questions, les griots en ce chant ont répondu :

« Il cultivera celui qui Aura choisi la culture, Et rien que la culture. Sun Jata n'est plus.

Il s'adonnera au commerce celui qui Aura choisi le commerce, Et rien que le commerce. Suba a vécu. »

Sun Jata repose à Nora... Et tous les vendredis, tard dans la nuit, des sons de clochette émanent de sa tombe. Et plus que les autres les griots ont pleuré : sentant la mort venir, il avait dit :

— Toute ma vie les Jeli m'ont servi de vêtements. Gens du Mande, faites qu'ils ne souffrent pas après ma mort.

Suba n'est plus, Nare Magan Konate s'en est allé...

« Etranger à l'aube,

Il était au soir le maître du pays.

Sun Jata a vécu

Jurons ! Jurons !

Mais pourquoi jurer ?

Le serment du pauvre

Peut-il valoir celui du riche ?

Suba n'est plus.

Chasseur forcené,

Conquérant irréductible

Nare Magan Konate s'en est allé.

Que le chien prenne au serIeux

L'os qui a résisté à l'hyène

Sun Jata a vécu.

La tête de l'homme

Ne ressemble pas

A celle de la femme.

Suba n'est plus.

Pour longue que soit ta route

Elle conduit toujours

En un lieu habité.

Nare Magan Konate s'en est allé.

Vieille souche ?

Guettez-la dans la nuit

Et elle vous guettera.

Sun Jata a vécu.

Chien de grenier ne connaît

Ni étranger ni autochtone.

Il ne sait que mordre.

Suba n'est plus.

Nare Magan Konate repose dans le pays

Qu'arrose le Sankarani.

Et les griots ont tant souffert...

Il cultivera celui qui

Aura choisi la culture,

Et rien que la culture.

Sun Jata n'est plus.

Il s'adonnera au commerce celui qui

Aura choisi le commerce,

Et rien que le commerce.

Suba a vécu.

Et les griots ont tant souffert... »

p. 53

(1) Suba : Autre nom de Sun Jata. Il signifie celui qui agit dans la nuit. Su (nuit) Ba est une contraction de baga (agent, instrument). Ainsi compris Suba veut dire : sorcier.

Sissoko, Bazoumana. 1970. Mali: Epic, Historical, Political and Propaganda Songs of the Socialist Government of Modibo Keita (1960-1968). Vol. 1. Recorded at Radio Mali 1960–64. Lyrichord, LLST7325, Albatros, VPA 88326.

(Sunjata)

This is one of the most famous epic songs of the Mali tradition, in celebration of Sunjata Keita, the founder of the Mali empire during the 13th century. According to tradition the song is supposed to comprise two verses composed by Bala Faseke Kouyate, a childhood friend of Sunjata and his griot. The refrain, instead, is supposed to be the creation of another griot, Tumu Manian, who followed Sunjata when the latter was exiled from Mande by his step-brother Mansa Dankara Tuman. Upon his return, Sunjata, the son of Sogolon Konte and Nare Fatta Ku Makan Kegni, after having overthrown all his enemies, founded the kingdom of Mali, the greatest in west Africa after Ghana, and which was at its greatest splendour during the reign of the emperor Kango Moussa, from 1312 to 1337. The story of Sunjata is also the national song of Mali. This performance by the griot Ba Zoumana from the province of Segou (in the Bambara language) is an example of the classical epic style of the griots of that area.

Ministère de l’information du Mali. 1971. Première anthologie de la musique malienne: 1. Le Mali des steppes et des savannes: Les Mandingues; 5. Cordes anciennes. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2501, 05.

(Sunjata)

This song bears the name of Sunjata Fasa, that is, Sunjata celebrated in his family tree, and compared with all those who have preceded him in the lineage of the Keita. It comprises two stanzas attributed to Bala Faseke Kouyaté, his friend from childhood and his regular griot (poet); the refrain, however, is said to have been composed by Tumu Manian, an old griote (poetess) who is said to have followed Sunjata into exile when he was chased out of Mandé by his half-brother Mansa Dankara Tuman. And it was on his return that Sunjata, son of Sogolon Konte and Nare Fatta Ku Magan Kegni, was to triumph over all his enemies in order to establish the Empire of Mali, the biggest in the West of Africa except for that of Ghana:

He has taken his bow, Sinbon!

Sinbon has taken his bow

To scour the savanna...

Sissoko, Bazoumana. 1972. Musique du Mali. Vol. 1. Bazoumana Sissoko, le vieux lion I. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2552.

(Sunjata)

Sunjata was the founder of the Empire of Mali in the 13th century. This song is widely known in the Malinké and Bambara countries.

Charters, Samuel, prod. 1975b. The Griots. Ministers of the Spoken Word. Folkways, FE 4178.

(Sunyetta)

"Sunyetta" was one of the great kings of the Mandingo...

(Soundjata Fassa)

p. 219

L'épopée de Soundjata est immortalisée dans le Soundjata Fassa, véritable cycle musical où tous les héros de Kirina sont évoqués ; c'est la création de Balla Fasseké, griot officiel du grand Empereur.

Suso, Foday Musa. 1978. Kora Music from Gambia. Folkways, FW 8510. Reissued in 1990. Smithsonian Folkways, 08510.

(Sunjata)

Sauta tuning.

This is the standard piece commemorating the greatness of Sunjata Keita, founder of the thirteenth century Empire of Mali.

Bird, Charles S., and Martha B. Kendall. 1980. "The Mande Hero: Text and Context." In Explorations in African Systems of Thought, ed. Ivan Karp and Charles Bird, 13-21. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Reprinted Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987.

(Sunjata)

p. 18

The Sunjata epic contains myriad examples of curses and countercurses effected as steps on Sunjata's way to heroic status. The first was the the result of circumstances attending his birth. Sunjata's father had two wives who became pregnant at the same time and gave birth on the same day. Sunjata was born second, but, as his name was announced first, his father proclaimed him as heir. The father's first wife became enraged and, "finding Sunjata's means," had a spell cast on him so that he could not walk for nine full years. Through the intercession of a jinn (and in some versions, a pilgrimage to Mecca), Sunjata finds the means to break the spell, makes the appropriate sacrifices, and rises. Striding out to his father's field, he rips a giant baobab from the earth, swings it atop his head, strides back to his mother's compound, and drives the tree into the earth before her house.

While he is involved in this heroic display, his mother, Sogolon Kutuma the hunch-backed sorceress, sings a long series of praise songs for her newly risen son, and in one of the songs she refers to him as "stranger":

| Luntan, luntan, o! | Stranger, stranger, Oh! |

| Sunjata kera luntan ye bi. | Sunjata became a stranger today. |

p. 19

Physical descriptions of heroes in tbe texts frequently elaborate their nonheroic qualities. Sunjata, for example, is portrayed as crippled and infirm until he overcomes tbe curse placed on him. Fakoli, one of his great generals, is characterized as exceptionally short, with an enormous head and a large mouth. The heroic stature of these men is nevertheless indexed in the nyama-laden objects they carry with them. In the Janjon, the Hero's Dance, these lines describe Fakoli's garb:

He entered the Mande

With skulls of birds

Three hundred three and thirty

Hanging from his helmet.

He entered the Mande

With the skulls of lions

Three hundred three and thirty9

Sunjata's great adversary, Sumanguru, receives the following awesome description in the Hero's Dance as well:

Sumanguru entered the Mande,

His helm of human skin.

Sumanguru entered the Mande,

His pants of human skin.

Sumanguru entered the Mande,

His gown of his human skin.

Knight, Roderic. 1982a. "Manding/Fula Relations as Reflected in the Manding Song Repertoire." African Music 6 (2): 37-47.

(Sunjata)

p. 39

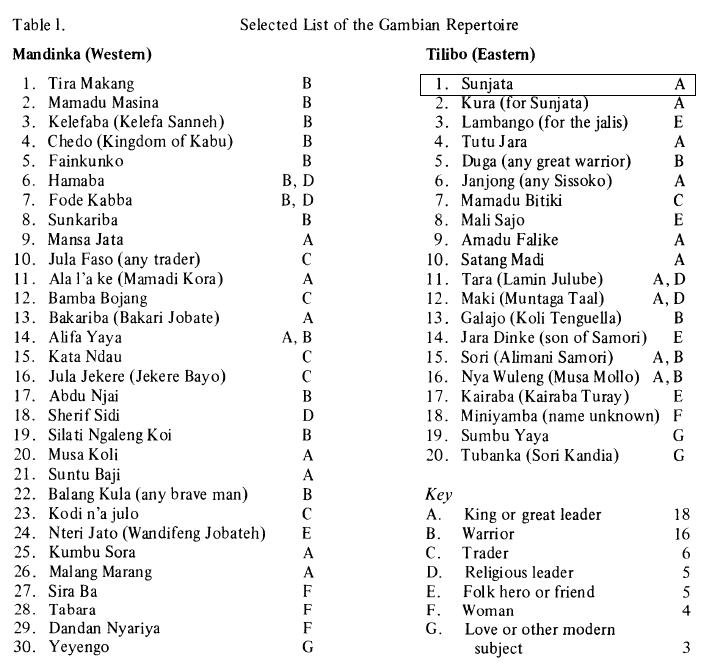

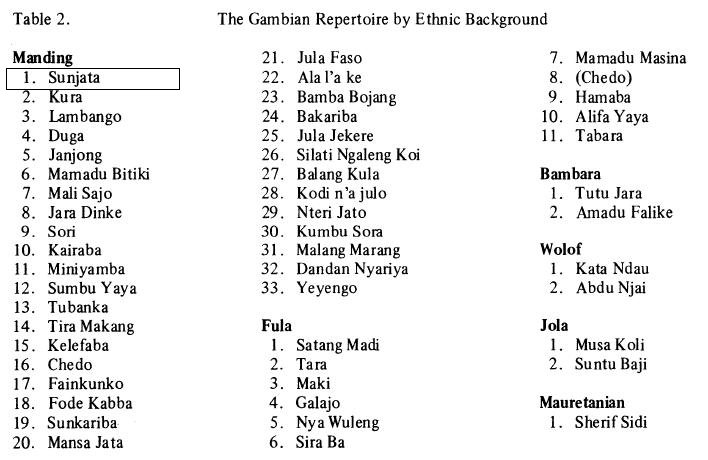

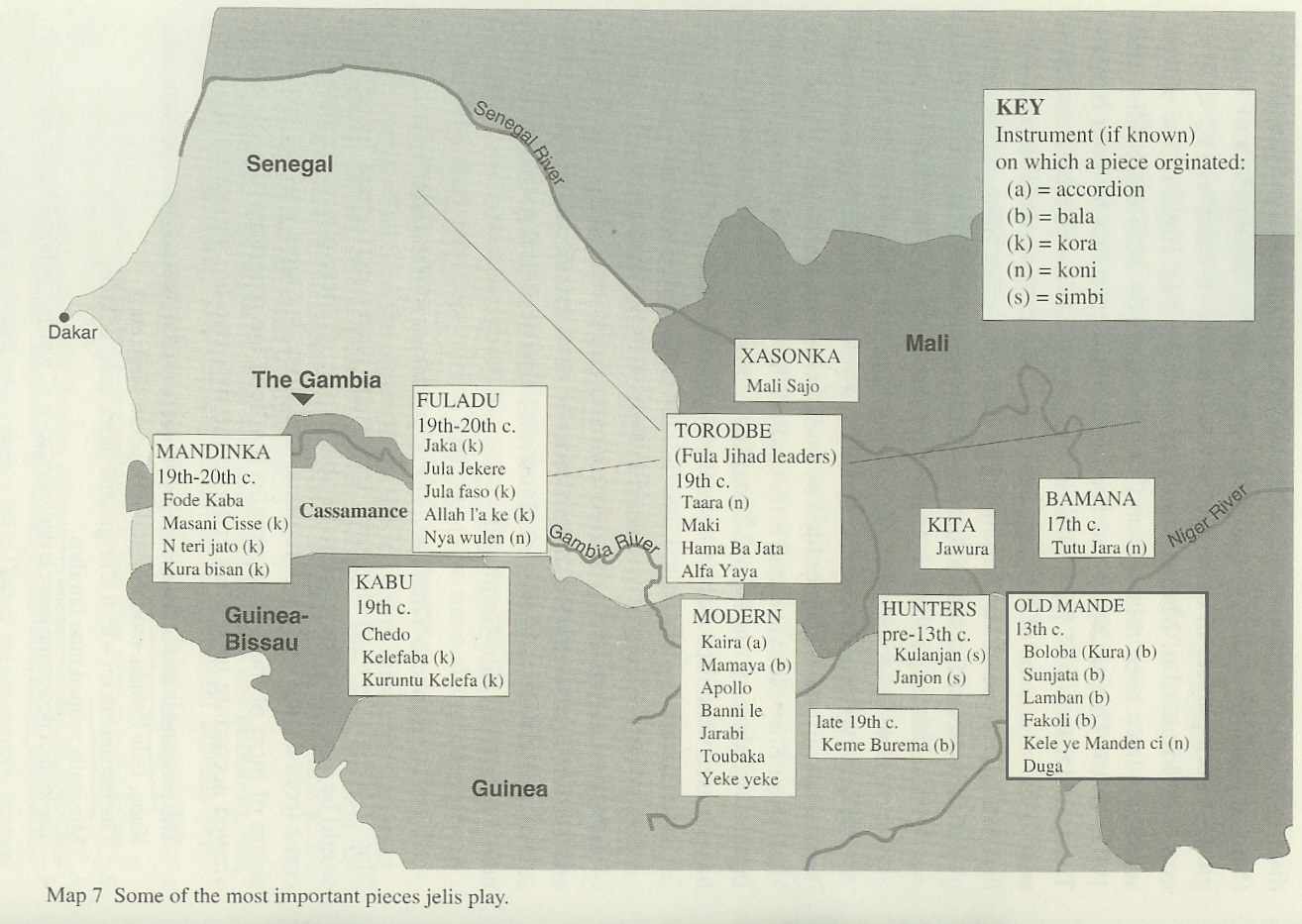

Table One . . . includes the best known, most often heard, or otherwise significant songs in the [Gambian] repertoire. In each column the top few songs are the oldest, and the bottom few are the youngest. The majority in each case fall somewhere in between (often in the nineteenth century), but no chronological ordering beyond this is intended, since it is often not possible to date a song exactly. Most of the songs bear the name of their owner as the title. Where they do not, his name is shown in parentheses next to the title. The letter code at the right represents the person's "claim to fame" or calling in life, as shown in the bottom of the list.

p. 40

Table Two shows the same fifty songs again, grouped this time by the ethnic background of the people commemorated.

p. 44

Musa Mollo himself, as with El Hadj Omar, appears not to have his own song, except for Nya Wuleng ("Red Eyes," symbolizing bravery), which has no text. However, it is very common for the jalis in the eastern regions of The Gambia to sing about him through most of a performance of Sunjata, Kura, or Tutu Jara, since his achievements have a more immediate appeal to present day audiences. A text that is frequently sung calls him the "great bar of soap," as valuable to the people as a bar of soap is to the women washing clothes

Coolen, Michael T. 1983. "The Wolof Xalam Tradition of the Senegambia." Ethnomusicology 27 (3): 477-498.

(Sunjata / Kelé Ké la Manding ti)

p. 480

Oral tradition insists that Anoukouman Doua, a thirteenth-century griot, played the molo at the court of the father of Sunjata, the Manding ruler who established the ascendancy of the Keita clan and founded the Mali empire.

p. 489

The largest proportion of traditional songs deals with the history and exploits of major leaders and warriors, such as Sunjata, founder of the Mali empire, and Alfa Yaya, the famous Fulbé warrior. Other songs deal with lesser-known historical figures. One such song is Tutu Jara, a story involving a king named Mansa Damanson, whose wife was unable to conceive children.

p. 490

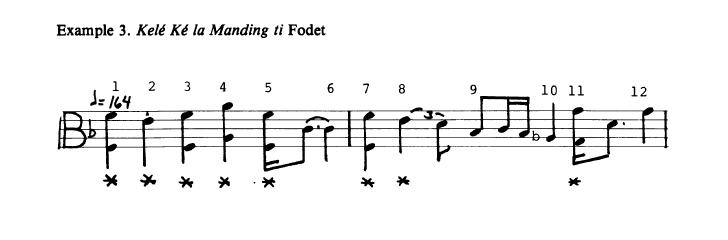

More commonly, fodets are bi-partite in structure, utilizing secondary tonal centers. The fodet for the tune Kelé Ké la Manding ti is a bi-partite fodet, using a 12-beat pattern with duple subdivision (ex. 3).

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Sunjata)

pp. 122–31

Introduction

The next series of tunes all relate to the epic of Sunjata and are presented here as a unit. There are many versions of the stories, songs, and myths that surround Sunjata, ruler of the Mali Empire. It is historical fact that he did live, was exiled, and returned to defeat his enemy, Sumanguru, in 1235. During his reign, the capital city of Niani, located in the heart of the Mali Empire between the Niger and Senegal rivers, became the richest city in the Western Sudan.

The Myth of Sunjata

Several scholars, using griots/jalis as informants, have published versions of the Sunjata epic. The story contains many of the classic motifs of myths, including motifs such as the lame child as hero, tests of identification, unique vulnerability, unique deadly weapon, and transformation to elude pursuers. (Thompson 1955-1958). There are several stories with accompanying music to commemorate different events in Sunjata's life. Strangely, there are none concerning his death. The following outline is only an overview of the story. Greater detail, narrative style, and specific incidents are contained in the publications used as sources.

Sources

Innes, Gordon. Sunjata - Three Mandinka Versions

- informants: Bamba Suso, Banna Kanute, Demba Kanute*

Niane. D.T. Sundiata, An Epic of Old Mali

- informant: Jali Mamodou Kouyate

Sidibe. B.K. Sunjata

- informants: Bamba Suso, Demba Kanote, Banna Kanote*, Jabir Kuyate.

* differences in spelling - authors each speIled the informants names differently, due to the lack of a standard orthography.

Sunjata — The Story

Fatakung Makung had ruled Manding for many years. He had several wives, but his diviners advised him that he should marry a woman named Sukulung who was ugly, but who would bear a child who would become king. He followed their advice, and Sukulung became pregnant, but for seven years. During that time one of Fatakung Makung's other wives also became pregnant. Fatakung said, "If any one of my wives bears me a son, I shall give my kingship to him" (Sidibe, p. 3).

Sukulung's son was born first, but the messenger sent to tell the king did not want to disturb him while he was eating, and while the messenger was waiting, another messenger from the other wife came and announced the birth of a son who was named as the successor.

Sunjata, angered by the injustice refused to learn to walk and could only crawl. His mother was scorned by the other wives who ridiculed her and her crippled son.

When it came time for Sunjata to go to circumcision, they would not help her gather the baobab leaves needed for the ceremony' saying that it was the boy's job. Sukulung was so humiliated she returned to her hut crying, and when Sunjata asked why, she told him that because he could not walk, she had to' suffer continual abuse.

So Sunjata called for the village smiths and told them to make him crutches of metal so that he could walk to the circumcision site. These were made and brought to him, but when he attempted to stand, his strength broke them. Saying: "Call my mother; when a child falls down it is his mother that picks him up", he put his hands on his mothers shoulders and stood. (Sidibe, p. 6)

He went to the baobab tree, uprooted it, and threw it down in front of his mother's house. He ate the fruit and said to his mother, "Now you can pick the fruit." (Sidibe, p. 6) The baobab that he had uprooted was one that the soothsayers had predlcted that whoever swallowed one seed of that baobab's fruit would become the king of Manding for sixty years.

Word of Sunjata's unusual strength and deeds spread to the neighboring kingdom of Susu where Sumanguru was the ruler. His diviners predicted that Sunjata would cause his downfall. Spurred on by that prediction and his brother the heir's jealousy, Sunjata, his mother, his sister Nyakalang Juma Suko, and Manding Mori, one of his brothers, left Manding and went into exile. They travelled to several kingdoms and were gone for many years.

Fatakung died, and the brother who had inherited the throne had been overcome by the more powerful Sumanguru. Both he and his sister Kassia had fetish powers, which Sumanguru used to intimidate and kill all rivals. Kassia's lover was the spirit being Manga Yura, who invented the balafon. He gave his balafon to Sumanguru but said he must play it himself, rather than have a griot sing his praises.

Kassia had a child by Manga Yura, and called him Faa Koli. This son was half human and half spirlt being. He grew up in Sumanguru's compound, and when he became of marriageable age he married s beautiful woman named Keleya. Sumanguru began to covet her, and finalIy told Faa Koli that he was not man enough to be her busband and abducted her. Faa Koli swore to get revenge and left for Manding where he asked for help in avenging his wife's imprisonment. It was decided by the elders to send for Sunjata to fight to regain the kingdom.

Famous generals and warriors were also summoned until a great body of men were gathered to fight. One of Sunjata's griots, Nyankuma Dookha, was sent to inform Sumanguru that Sunjata had entered Manding. While he was in Sumanguru's palace, Nyankuma saw the balafon hanging inside a room and could not resist taking it down and playing it. When Sumanguru heard someone else pIaying his balafon, he insisted that Nyankuma stay and become his own griot. He cut his Achilles' tendon so that he could not leave. Then he renamed him Bala Fasigi Kuyate. (Bala - balafon, Fasigi - Achilles' tendon, Kuyate - surname). When the people of Manding heard what had happened to the griot, they became even more enraged.

Among the generals who came to fight with Sunjata were Kuma Fofana, Surubanda Makang Kamara, Sankarang Madiba Konteh, Faa Koli, Sora Musa and Tiramakang. They fought many battles, but by using his fetish powers Sumanguru managed to win each time.

Finally, Sunjata's sister Nyakalang decided to use her beauty to see if she could find out the secret of Sumanguru's power. She left Sunjata's camp and went to the fortified town of Kankinyang where Sumanguru was staying. When he saw her, he was attracted by her great beauty snd invited her to his house. She told him she was tired of the fighting and had advised Sunjata to give up, but since he had ignored her advice, she had come to Sumanguru to marry him.

He desired her very much, but Nyskalang reminded him that before freeborn people form an intimate relationship with each other, they must tell each other of their taboos; what could strengthen them or weaken them.

At this point, Sumanguru's mother, who was sitting in a corner of the room, warned Sumanguru: "Don't tell your secrets to a one-night woman."

Sumanguru however, gave his mother some palm wine, and she fell asleep, whereupon he told his secrets to Nyakalang.

His power was a jinn who lived under the hill the town was built on. If it was killed, Sumanguru's power would end. So nyankalang asked how the jinn could be killed. He replied that the spur of a white cock with coos Ieaves and korte powder put on the tip of an arrow and shot into the hill would kill the jinn. At that point Sumanguru would turn into a whirlwind, but if attacked, he would turn into a palm tree, If anyone tried to fell the tree he would become an anthill, and if that was scattered, he would turn into a bird.

Once Nyankalang found out his secrets she excused herself on the pretense of going to take a bath, instead she climbed the wall of the wash place and went back to Sunjata's camp where she told all she had found out.

So the magic arrow was prepared, and Sankarang Konte rode to Kankinyang and shot it into the hill, killing the jinn and destroying Sumanguru's fetish power. The next morning the Manding army marched on Kankinyang and proceeded to destroy it. A great whirlwind rose up, and Nyakalang, knowing it was Sumanguru, sent soldiers to rush it, however he turned into a palm tree so they tried to cut it down, but he changed into an anthill; just as they were ready to smash it, they saw a bird fly off into the bush.

So Sunjata took over the kingship of Manding and ruled for many years.

Donkilo

(on teaching tape)

| Iye bara kala ta | |

| Suku lum ba bara kala ta | |

| Kai iya la la |

(from: Knight, 1973)

| A bara kala ta le, Jata | He has taken his staff, Jata |

| A bara kala ta le, Simbon | He has taken his staff, Great Hunter |

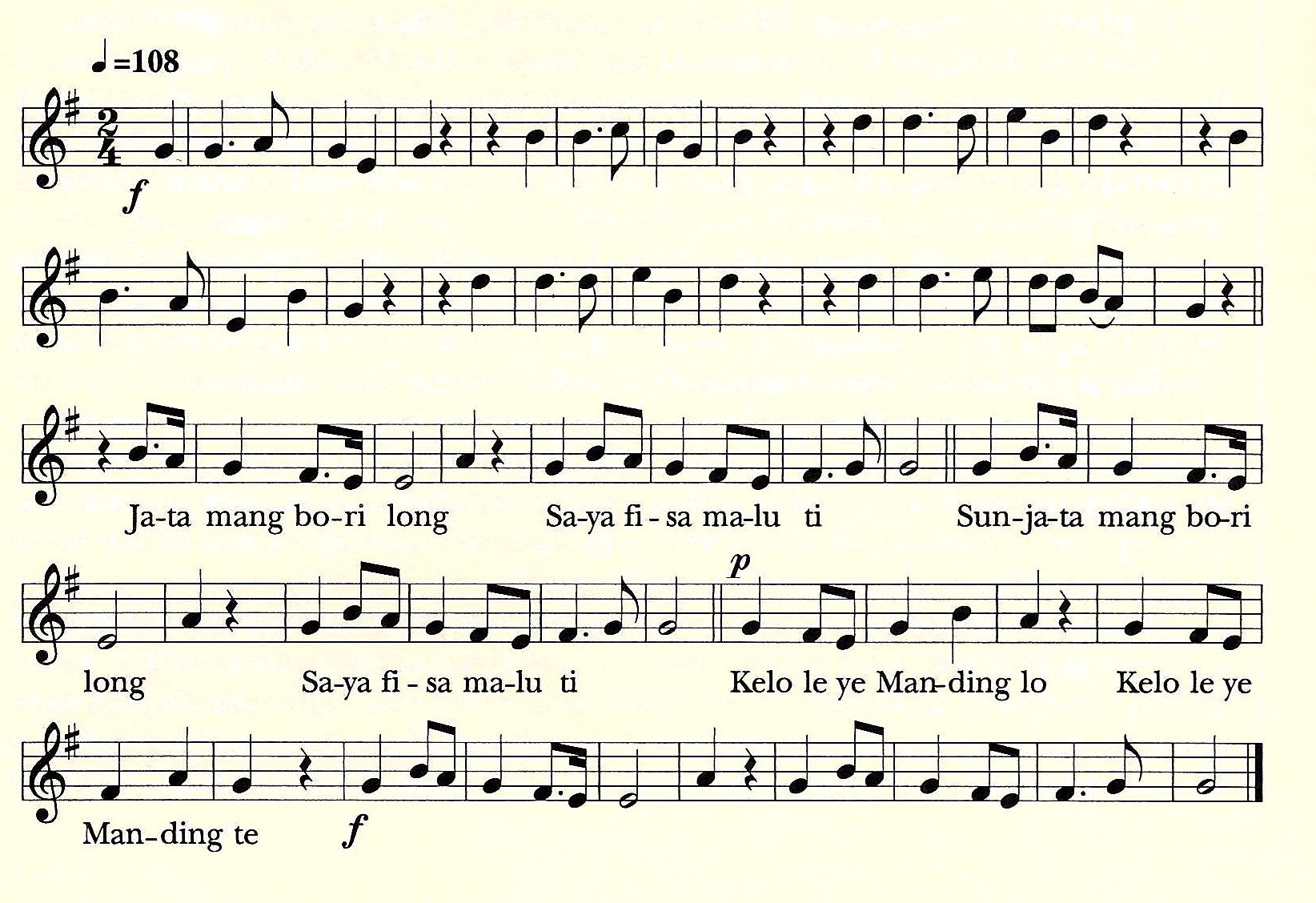

Kelo Le Ye Manding Lo

pp. 138-39

Donkilo

(on teaching tape)

| Kelo le ye mandi te | It was the war that broke Manding |

| Kelo le ye mandi lo | It was the war that built Manding |

(from: Knight, 1973 2:5)

| Kelo le ye mandin lo | It was the war that built Manding |

| Kelo le ye mandin le | It was the war that broke Manding |

| Jali kuma le ye Mandin lo, | It was jali words that build Manding, |

| Jali kuma le ye Mandin te | And jali words conquered Manding (again). |

pp. 146-59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Kelo Le Ye Manding Lo |

| Translation: | War built Manding |

| Dedication: | |

| Notes: | part of the Sunjata epic |

| Calling in Life: | |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon, Kora |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | M (19th & 20th c. up to WWII) |

| Sources: | 1, 5 (Jessup & Sanyang, M. Suso) |

Kura

see: Boloba (Kura)

Nyaama, Nyaama, Nyaama

pp. 132-33

Donkilo

(on teaching tape)

| Nyaama, nyaama, nyaama, | Grass, grass, grass, |

| Feng ne be dungna nyaama kono | Something can enter grass, |

| Nyaa te dungna feng feng kono | The eye cannot enter anything. |

(from: Knight, 1973 2:5)

| Nyama, nyama, nyama | Grass, grass, grass |

| Fen ne be dunna nyama le koro | Something may enter the grass (to hide), |

| Nyama te dunna fen fen koro | (but) the grass does not go down under anything |

Related information

Nyaama means grass. The imagery refers to the Keita family of Sunjata's lineage, who would not lower themselves below anyone. The basis of the imagery is unknown.

pp. 146-59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Nyaama, Nyaama, Nyaama |

| Translation: | Grass, grass, grass |

| Dedication: | Sunjata |

| Notes: | |

| Calling in Life: | king or leader |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | E (13th & 14th c.) |

| Sources: | 1 (Jessup & Sanyang) |

Sunjata Mang Bori Long

pp. 136-37

Donkilo (on teaching tape)

| Sunjata mang bori long, | Sunjata knows not running, |

| Sumanguru, | Sumanguru. |

pp. 146-59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Sunjata Mang Bori Long |

| Translation: | Sunjata knows not running |

| Dedication: | Sunjata |

| Notes: | |

| Calling in Life: | king or leader |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | E (13th & 24th c.) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

Sunjata Naata, Sumanguru Kante

pp. 134-35

Donkilo (on teaching tape)

| Sunjata naata, | Sunjata comes, |

| Sumanguru, kante | Sumanguru, watch out. |

pp. 146-59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Sunjata Naata, Sumanguru Kante |

| Translation: | Sunjata is coming Sumanguru |

| Dedication: | Sunjata |

| Notes: | |

| Calling in Life: | king or leader |

| Original Instrument: | Balafon, Kora |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | E (13th & 24th c.) |

| Sources: | 1, 5 (Jessup & Sanyang, M. Suso) |

Haydon, Geoffrey, and Dennis Marks, dirs. 1984. Repercussions: A Celebration of African American Music. Program 1. Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia. Chicago: Home Vision.

(Sunjata)

The balo and the kora; the piece is Sunjata, one of the oldest in the Mandinka repertoire and still one of the most popular.* It was composed for Sunjata, the most famous of the Manding emperors. . . .

. . . [When] Sunjata found the first musician, Balafa Seexu Kuyaate, his instrument had only three keys. He found him sitting in a baobab tree. The baobab tree had a huge hollow and that's where Sunjata found the musician.

* Transcription mine. Orthography based on Jatta (1985).

Knight, Roderic. 1984. "The Style of Mandinka Music: A Study in Extracting Theory from Practice." In Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, vol. 5, Studies in African Music, ed. J. H. Kwabena Nketia and Jacqueline Cogdell Djedje, 3-66. Los Angeles: Program in Ethnomusicology, Department of Music, University of California.

(Sunjata)

p. 8

Another major theme in the donkolo texts is bravery, usually in the form of prowess in battle. The oldest song on this subject is "Duga", . . . This "solemn Vulture's Tune" is mentioned in the story of Sunjata.

Jatta, Sidia. 1985. "Born Musicians: Traditional Music from The Gambia." In Repercussions: A Celebration of African-American Music, ed. Geoffrey Haydon and Dennis Marks, 14-29.

(Sunjata)

p. 23

The Mandinka repertoire consists of some pieces with date back to the twelfth century, the time of the ancient Mali Empire under the reign of Sunjata, the most famous of the Manding emperors. One such piece is Sunjata, so called because it was composed for the emperor.

The repertoire also contains contemporary pieces. These are either new compositions or modified and developed versions of old ones. As far as I know, at least two new versions of the Sunjata piece have been developed: one by the Sidiiki school and one by the Bantuuru school.

p. 24

New versions have also been developed to accompany new ways of playing the pieces. For example, the two new instrumental versions of the Sunjata piece have corresponding new versions of the epic song. Furthermore, there is the practice of changing the words of a song and substituting new ones to conform to the occasion. When the Sunjata piece is played for a patron, for instance, the singers replace Sunjata's praise-names with those of the patron in question. Thus, although the same pieces are played for different patrons, the song content varies.

Sadji, Abdoulaye. 1985. Ce que dit la musiqe Africaine.... Paris: Présence Africaine.

(Soundiata)

pp. 11-38

Sur ces Empires noirs d'autrefois que l'Histoire connaît imparfaitement : Empire du Mali, de Songhay, de Ghana et de Tekrour, les peuples soudanais entretiennent des légendes qu'ils ne dévoilent pas sans une certaine frayeur.

Il semble qu'un fils du Manding ne saurait parler impunément de Soundiata-Keita s'il n'éprouvait au préalable un certain bonheur, une certaine joie, une exubérance manifeste.

Pour me faire compter l'histoire de l'ancêtre des Mandings, j'ai dû tour à tour me faire libéral, persuasif. Car le diali redoutait la colère de certaines divinités très vagues. Que faire pour le décider ?

A la fin il me promit de parler de Soundiata, mais à une seule condition: c'est que je fisse mon possible pour qu'il fût réellement heureux ce jour-là.

Etait-il sincère, mon diali ?

Les jours succédèrent aux jours et, en attendant le moment de grâce, il me parla d'autres héros partis de rien et qui ont su, par leur audace, s'imposer à leurs peuples.

Un jour il me dit :

— Demain, je vous parlerai de Soundiata. Préparez tout ce que vous pourrez pour que je sois content demain.

Et le lendemain, il accorda son instrument avec plus de soin et se mit à jouer pendant longtemps sans parler, comme pour écouter un interprète mystérieux de la gloire du grand Manding. Puis tout à coup, il parla solennellement.

Le monde a commencé à Ouagadou. C'est là qu'on place le début de tous les événements de la terre.

Le monde sortait nouvellement du chaos, les pesantes ténèbres de la pré-vie, les vapeurs et la nuit qui enveloppaient l'univers, tout venait d'être dissipé. Et Ouagadou, un point ignoré de beaucoup d'hommes, là-bas en Afrique Occidentale, était le théâtre de la première réunion des créatures de Dieu.

Ouagadou sanctuaire des peuples ?

Le commencement de toute chose s'y révéla, me dit le diali. Les hommes, les animaux et les plantes y reçurent leur destinée. C'est là qu'on fit le partage des terres que n'occupaient que les eaux. Alors tous les vivants se quittèrent et par groupes s'en allèrent vers la terre promise. Mais ils se rencontrèrent de nouveau au Manding où régna la plus complète anarchie. Les plus forts fondaient sur les faibles, car nul ne commandait aux hommes, en ce temps-là.

Or, Narman-Diata se leva pour parler à tous les peuples. Il dit :

— Les hommes ne sauraient vivre sur la terre sans qu'il y ait un chef. Je veux devenir le chef du Manding. L'acceptez-vous ?

Tous répondirent :

— C'est vrai, Ko-naté.

Ko-naté signifie « nul ne te hait ». C'est à cet instant que Narman-Diata prit le nom de Konaté, qui devint son nom de famille.

Il commença son règne sur le Manding, avec pour chancelier et ministre, le grand chasseur Tiramakan. Tiramakan fut le premier chasseur de la terre. Il est l'ancêtre de ceux qui sont nés ennemis des biches, des antilopes, des lions et des tigres. Il est l'ancêtre des vrais chasseurs, dont la balle atteint toujours son but.

Tiramakan chassait non seulement le gibier à poils et à plumes (le gibier visible qui creuse des trous ou court dans les fourrés), mais il chassait un autre gibier invisible et dangereux, celui des djinns, des sorciers, des esprits malfaisants qui reviennent sur la terre pour faire du tort aux hommes. Il avait des sachets remplis de poudre mystérieuse et sa bouche était pleine d'incantations terribles.

Tiramakan chassait non seulement avec le fusil et l'arc, mais aussi avec le couteau, la pierre, les oeufs, la salive, avec son regard et ses propres excréments.

Or, il y avait à Sankaran une femme qui était une grande sorcière. Elle se transformait généralement en buffle. Et tous les hôtes du village, elle les emmenait dans la forêt, se battait avec eux, les tuait et les mangeait.ment.

Le buffle semait la terreur sur tout Sankaran.

Les citoyens du village mandèrent un des leurs auprès de Narman-Diata-Konaté en disant :

— Nous avons appris que tu as le plus fameux chasseur de la terre. Qu'il vienne donc nous débarrasser du buffle qui mange tous nos hôtes.

Tiramakan partit pour Sankaran, emportant avec lui un arc et des flèches, un fusil, puis un charbon, une pierre et un oeuf. Il alla droit chez le chef de Sankaran.

— Ah ! tu es venu ! lui dit ce dernier.

— Oui, répondit Tiramakan.

— Voilà dans la forêt, dit le chef de Sankaran, la case de la grande sorcière qui mange tous les étrangers, hôtes de ce village.

Or, cette sorcière était l'ancêtre de tous les sorciers depuis les événements de Ouagadou. C'est pourquoi elle était si puissante.

Tiramakan quitta le village et devint l'hôte de la vieille sorcière.

Elle reçut le chasseur on ne peut plus gentiment, car elle l'avait vu venir de très loin et avait tout préparé pour le recevoir. L'intelligence d'un sorcier est immense et son oeil profond. Cet oeil ne tient nul compte de la nature extérieure qui développe partout des obstacles. Cette intelligence connaît les moindres mobiles des hommes et égale en maintes situations celle de Dieu. A plus forte raison quand il s'agit de la première sorcière que la terre eût vue, on peut penser que la création l'avait dotée d'une puissance en tout supérieure à celle de ses descendants, les sorciers de maintenant, qui arrivent souvent, par faiblesse, à trahir leur espèce. Les sorciers de maintenant trahissent leur espèce, car les hommes sont arrivés à leur faire avaler des breuvages qui les font parler.

Le lendemain, Tiramakan dit à la vieille sorcière :

— Maintenant je veux m'en retourner au Manding. Et il la quitta effectivement.

La vieille sorcière était sournoise. Elle avait vu venir Tiramakan de très loin et malgré la belle réception qu'elle lui avait réservée, elle connaissait bien le but de son voyage.

Tiramakan quitta la vieille sorcière et s'enfonça de nouveau dans la forêt. Au milieu de la forêt, il vit tout à coup un buffle qui l'attendait. Ille reconnut aussitôt: c'était la vieille sorcière. Le buffle lui dit :

— Tiramakan, prépare-toi, car je vais te combattre.

Et sans plus attendre, il bondit sur lui. Le buffle bondit avec fracas, comme s'il écrasait la terre entière sous lui. Tiramakan lança contre cet adversaire de taille une première balle qui se changea en eau. Son coeur bondit alors, dans un petit désespoir vite dissipé. Et le buffle ricana fort gaiement :

— Hé ! hé ! hé ! ah ! ah ! ah ! J'arrive, Tiramakan.

Tiramakan lança le charbon qui se changea en une mer de feu entre lui et le buffle. Le buffle cracha sur le feu qui s'éteignit. Et le feu, en s'éteignant, rapprocha davantage les deux adversaires. Tiramakan tira de nouveau. Et la seconde balle, comme la première, se changea en eau.

— Hé ! hé ! hé ! ah ! ah ! ah ! duel ridicule, inégal !

Tiramakan jeta la pierre entre lui et le buffle. La pierre devint une montagne très haute. Le buffle tourna son derrière contre la montagne et la fit éclater en y envoyant une vesse formidable. Puis il fondit de nouveau sur Tiramakan. Celui-ci lui envoya une troisième balle, qui ainsi que les deux autres se changea en eau. Il lança ensuite l'oeuf qui forma entre eux un océan très vaste. Mais le buffle se pencha et but la mer d'un seul trait. C'est alors que Tiramakan fit un excrément très chaud avec lequel il chargea son fusil. Et il tira sur le buffle qui fut atteint à la poitrine et tomba.

— Hé ! hé ! hé ! ah ! ah ! ah !

La forêt, dérangée par l'immense bruit de cette lutte, reprit peu à peu son silence profond ; mais les montagnes s'envoyèrent longtemps, après le combat, les échos de la gaîté du buffle et la sourde terreur de Tiramakan.

Alors Tiramakan dit :

— Dougou tiguini blé, blé fan kanta Ya ani moni (le chef d'une ville peut commander impérieusement à ses sujets, mais le sujet est dans sa maison et regrette). Ayant dit, il saisit un couteau et se mit à tailler profondément dans le corps du buffle. Il lui coupa la queue et les oreilles et mit tout cela dans son sikara. Puis il reprit le chemin de Sankaran. Il alla trouver le chef du village et lui présenta la queue et les oreilles du buffle en disant :

— Voici la queue et les oreilles de celle qui mangeait les hommes dans la forêt.

Le chef du village fit battre le tabala d'allégresse et tous les notables de Sankaran suspendirent leurs travaux ou leurs pensées pour gagner la place des réunions. Le chef leur montra la queue et les oreilles du buffle. Et désignant simplement Tiramakan du doigt, il dit :

— Voici celui qui l'a tué.

On fit venir une jeune fille vierge, une femme libre et une femme mariée. Tiramakan devait choisir parmi les trois. On lui dit :

— Maintenant, choisis parmi elles la femme que tu voudras, car tu viens de faire ce qu'aucun mortel n'était capable de faire.

Il choisit non parmi les trois qu'on lui présentait, mais parmi toutes celles de Sankaran. Il choisit une nommée Sogolon-Koudouma. Puis il fut autorisé à l'emmener au Manding.

Tiramakan refit le même chemin pour retourner au Manding, ayant tué l'ancêtre des sorciers qui existait depuis les événements de Ouagadou.

Il fit présent de la femme qu'il avait choisie à NarmanDiata, maître des terres et de tout ce qui y vivait. Il dit à Narman-Diata :

— Prends cette femme, je te la donne. Tu en feras ton épouse.

Narman-Diata épousa la femme qui avait nom Sogolon-Koudouma.

Sogolon-Koudouma fut enceinte. Sa gestation dura neuf ans. Or tout le pays interpréta mal ce signe. On disait :

— Qu'est-ce que Tiramakan nous a ramené de Sankaran ? A-t-on jamais vu grossesse qui dure neuf ans ?

Chacun croyait que Sogolon-Koudouma était atteinte du mal terrible. Un jour où elle causait assez bruyamment avec une aj.ltre femme du roi, celle-ci lui dit avec malice :

— Tu ne pourras jamais nous faire croire que tu portes un enfant dans ton sein. Dis seulement que tu es malade pour qu'on te guérisse vite.

Or l'enfant, dans le ventre de sa mère, avait entendu ces propos. Il dit tout à coup:

— Mère, entre dans ta case et mets-moi au monde, car mon temps est révolu.

C'était la neuvième année de la grossesse de Sogolon-Koudouma.

La mère obéit et mit au monde un enfant du sexe fort. On manda un esclave auprès de Narman-Diata-Konaté pour lui dire que sa dernière femme avait donné un enfant du sexe fort. Et Narman-Diata-Konaté congédia l'esclave en disant :

— Va et dis-leur que je donne à l'enfant le nom de Soundiata (soun : surprise, diata : lion).

Mais l'enfant refusa le sein de sa mère. Pendant huit mois, il demeura sur place sans pouvoir se lever ni se traîner. Il était paralytique.

Un autre jour, l'une des femmes de Narman dit à Sogolon-Koudouma :

Ah, je savais bien que tu mettrais au monde un empoté, un être incapable de bouger.

Soundiata, l'ayant entendue, fit venir sa mère et lui dit :

— Va et dis à mon père de réunir tous les forgerons du Manding, qu'il leur dise de me fondre une lance très solide afin que je m'appuie dessus pour me lever.

La lance fut faite, et il fallut quinze hommes choisis parmi les guerriers pour la porter auprès du jeune Soundiata.

A cette époque, il n'y avait sur la terre ni coras, ni guitares, ni violons. Un petit arc qu'on faisait vibrer entre les dents—une espèce de monocorde—était seul connu.

On porta la lance au jeune Soundiata qui s'y appuya et se tint debout. Son premier acte fut de monter à cheval et d'aller rendre visite à son père.

Le lendemain ce dernier mourut.

A la mort de Narman-Diata-Konaté, tout le Manding fut rassemblé. On lui rendit les honneurs dus à sa puissance et à son règne. On évoqua les événements de Ouagadou, le courage et la force de caractère du défunt lorsqu'il s'était levé le jour du partage des terres disponibles pour demander le commandement des hommes. Quelques anciens se doutaient déjà que peut-être nul ne pourrait plus égaler Narman-Diata en puissance et en sagesse.

Mais Soundiata se leva avant que leurs pensées eussent pris forme. Il s'adressa au peuple en disant :

— Vous qui abreuvez la terre de vos larmes abondantes, tournez vos regards vers moi et recueillez-vous un moment, puis écoutez ensuite mes paroles. Car je vous le dis en vérité, ceux qui ne peuvent pas vivre sous le règne d'un roi autre que mon père, n'ont qu'à se montrer: je les exterminerai sur l'heure et leurs corps iront là où va celui de Narman-Diata-Konaté, mon père.

Mais le pays entier se déclara favorable, disant :

— Keita, hérite ! Deviens roi !

C'est depuis ce moment que le nom de Keita fut connu des hommes. Et Soundiata s'appela désormais: Soundiata-Keita.

La naissance des choses a commencé depuis les événements de Ouagadou ; elle s'est continuée sous NarmanDiata-Konaté et après lui sous Soundiata-Keita. Mais elle ne s'est pas poursuivie après Soundiata.

Lorsque Soundiata mourut, toutes les choses sur la terre étaient définitivement créées, et toutes avaient chacune sa destination.

En un seul jour, aidé de son ami Balafacé-Kouyaté, Soundiata-Keita se rendit maître de toute la terre. Car partout, quand ils le voyaient, les peuples se disaient entre eux :

— C'est le fils de Narman-Diata-Konaté, celui qui s'est levé pour commander aux hommes lors des événements de Ouagadou. Et il ressemble à son père par la tête et par le caractère.

Un jour, en se promenant avec son ami le long d'une rivière, le son de la cora: parvint à l'oreille humaine. Car, jadis l'homme ne connaissait pas la cora. Il n'y avait sur la terre ni coras, ni guitares, ni violons. La cora fut à l'origine la propriété du djinné (diable). L'homme était semblable à une larve et aucun instrument ne lui permettait d'élever son âme et de conserver par la musique la gloire des héros.

Or les sons de la première cora parvinrent aux oreilles de Soundiata et de son ami, combinés par les doigts invisibles d'un djinné qui habitait dans la rivière.

Soundiata dit à son ami de l'attendre. Puis il entra dans la rivière et livra bataille au djinné pour lui enlever la cora. De leur lutte tumultueuse naquirent les vagues grandes ou petites qui froncent la surface tranquille des eaux. Soundiata sortit vainqueur du combat, rapportant la cora enlevée au djinné, et qui devait être la première de la terre.

De retour à la maison, son ami Balafacé-Kouyaté l'interrogea :

— Pourras-tu jouer de cet instrument ?

Soundiata répondit :

— Attends, je vais jouer.

Et il se mit à jouer son premier air de gloire qu'on peut traduire ainsi :

Moi, Soundiata, je suis venu dans Souma-Woro L'Homme connaît les yeux de l'homme.

Puis son ami lui demanda la cora et se mit à jouer le même air. Alors Soundiata ferma les yeux, remua doucement la tête et dit :

— Ah ! ah ! Il est plus doux d'entendre la musique par la main d'un autre que par sa propre main.

Et désormais il ne toucha plus à la cora. Son ami eut la charge de jouer partout pour ·lui. C'est depuis ce moment qu'il y a des griots pour crier à vos oreilles, les jours de combat, afin de fouetter le sang noble des héros vivants.

Balafacé-Kouyaté est donc l'ancêtre des griots, comme Tiramakan fut celui des chasseurs à arc et à flèches et des arquebusiers.

Soundiata fit venir Tam-Diara-Fodé, ancêtre de ceux qui portent le nom de Camara. Il fit venir FakolyKoumba, ancêtre de ceux qui portent le nom de Sissoko ou Guèye. Il fit venir Manka-Dandouma, ancêtre de ceux qui s'appellent Gassama ou Diabi. Il fit venir Tiramakan, ancêtre des chasseurs et de ceux qui s'appellent Travelé (Traoré) ou Diop. Il vit venir Moulaï-Bakary, ancêtre de ceux qui s'appellent Courbaly ou Fall. Il fit venir MangaFifra, qu'on surnommait le Roi Suprême parce qu'il était à l'origine de la noblesse du pays. Il fit venir tous les grands du pays et leur dit :

— J'ai hérité de mon père. ah !

On lui répondit :

— C'est vrai, mais avant d'être roi, regarde, il y a non loin du village un baobab. Ton père n'a pas pu le faire tomber. Ton grand-père n'a pas pu le faire tomber. Si tu le fais tomber, toi, tu seras roi du Manding aux yeux de tous.

Or, ce baobab, chaque fois qu'on l'abattait, se relevait de lui-même aussitôt et recommençait à vivre.

Soundiata leur dit :

— Je ne vous promettrai pas de le faire tomber demain ou après-demain. Allons tout de suite vers le baobab, que je le fasse tomber devant vous.

Puis il demanda à qui appartenait le baobab. TamDiara- Fodé se leva et répondit:sclave.

— C'est à moi qu'appartient ce baobab. En lui vit l'âme de mes aïeux qui furent anciens parmi les anciens du Manding. Et nul ne pourra faire tomber ce baobab. Il a été créé par le génie puissant pour régner sur la terre.

Soundiata s'adressa avec impatience à Tam-Diara-Fodé en disant:

— Et maintenant, va donc te mettre au pied du baobab.

Ses yeux étincelaient de conviction et de rage, car l'oeuvre à accomplir lui semblait petite. Or tout le Manding s'était réuni pour assister à l'abattage du baobab.

Tam-Diara-Fodé s'entretint pendant longtemps avec son baobab en langue inconnue. Mais déjà Soundiata s'était avancé vers l'arbre et voici qu'il posa un de ses pieds sur Tam-Diara-Fodé et l'autre sur le baobab. Ayant fait, il porta un coup rude à l'arbre qui tomba, racines en l'air. Sa chute fut accueillie par un long soupir des anciens. Tam-Diara-Fodé commanda au baobab de se relever. Mais Soundiata commandait au baobab de se coucher. Une mystérieuse contradiction naquit au sein du baobab, qui obéissait tantôt à Tam-Diara-Fodé quand celui-ci lui parlait, tantôt à Soundiata quand ce dernier commandait à son tour. Et l'âme du baobab, sollicitée d'un côté et de l'autre par deux volontés très fortes, forcée d'obéir à l'une et à l'autre, faisait faire à l'arbre tout entier un lourd mouvement d'oscillation qui était douloureux à voir. Mais le baobab recevait une secousse plus forte quand la voix de Soundiata éclatait. Quand il eut la tête en bas et les racines en haut, Tam-Diara-Fodé abandonna l'espoir de lui redonner vie. En effet, le baobab ne se releva jamais.

Alors Tam-Diara-Fodé se retourna vers Soundiata et dit longuement les louanges de ce dernier. Il disait :

— Le passé est grand et nous donne des lois. Mais le présent peut commander au passé.

Soundiata répondit :

— Je suis venu, moi, Soundiata, dans Souma-WofO. L'homme connaît les yeux de l'homme.

Balafacé l'accompagnait à la cora. Puis il ajouta: « J'ai eu pour tuteur Tiramakan et je suis venu de Sankaran dans le ventre de ma mère. Tiramakan est l'ancêtre des chasseurs qui ne sont jamais vaincus par le gibier. Je suis venu de Sankaran du bout du monde, pour naître dans le Manding afin de remplacer celui qui commandait aux hommes, j'ai nommé Narman-Diata-Konaté, mon père. Tiramakan a vaincu la grande sorcière, et c'est lui mon tuteur. »

A la fin de chaque parole, Tam-Diara-Fodé et tous les anciens soupiraient. Mais le baobab ne se releva jamais plus.

Soundiata revint dans sa maison. Or il avait une soeur qui était jalouse de sa gloire.

Pour mettre rapidement fin aux jours de Soundiata, chaque matin elle se déshabillait et s'asseyait sans vêtement sur le seuil de sa porte. Et Soundiata en sortant la voyait dans cet état.

Cependant, il est mortellement dangereux de voir la nudité des personnes plus âgées que vous. Le diable habite dans les parties génitales de l'homme. Il les quitte de bon matin avant l'heure des premiers feux du soleil. Et si vous n'êtes pas homme à tête surnaturelle, prenez garde le matin, de laisser tomber votre vue sur le basventre d'une personne âgée. Car le moins qui puisse arriver est de n'avoir aucune chance dans la journée.

Soundiata fit appeler sa soeur et lui demanda :

— Pourquoi te présentes-tu toute nue devant ma porte? Ne sais-tu pas ce que je fais aux hommes dans la forêt? Tu vas le savoir aujourd'hui. Je vais t'emmener dans la forêt pour que tu voies cela.

n ordonna à ses esclaves d'attacher fortement sa soeur. On la hissa ensuite sur un cheval, de façon qu'elle puisse voir s'accomplir les exploits de Soundiata.

Soundiata alla vers le Balédougou et, en apercevant le village, il cria :

— Sauvez-vous, car je viens.

Une flamme sortit de sa bouche, qui enflamma une case, puis deux, puis trois, et dévora tous les alentours. Et Soundiata, se tournant vers sa soeur, lui dit :

— Regarde.

La soeur eut tellement peur qu'elle sentit ses entrailles se nouer.

Elle le supplia de ne pas continuer à semer la terreur. Elle dit :

— Ne fais pas cela, mon frère. Retournons au Manding.

Alors Soundiata se souvint que sa soeur n'avait jamais eu de mari. Il répondit, menaçant :ne se

— Quand nous serons au Manding, je te marierai à quelqu'un, car depuis ta naissance tu n'as jamais eu d'amant.

La soeur fut saisie d'une telle peur qu'elle en eut des troubles d'estomac pendant près d'une quinzaine de jours.

Si je savais mettre en notes la musique qui conserve la mémoire de Soundiata-Keita, je le ferais pour disposer le lecteur à aimer ce souverain puissant entre tous, qui était venu de Sankaran dans le ventre de sa mère, laquelle avait nom Sogolon-Koudouma ; je le ferais pour donner une idée de la musique la plus ancienne du monde, donnée par le premier instrument de la terre, je le ferais pour montrer qu'elle caractérise bien le chaos primitif qui précéda immédiatement les événements de Ouagadou dont tous les êtres vivants sont issus.

Ils revinrent au pays et il donna sa soeur en mariage à Fakoly-Koumba, l'ancêtre de ceux qui s'appellent Guèye. Puis il fit venir tout le Manding et lui parla ainsi :

— Je viens de marier ma soeur, car elle n'a jamais eu d'amant.

On lui demanda vivement :

— A qui l'as-tu mariée ?

Et il répondit :

— A Fakoly-Koumba.

L'un des hommes était remarquable par sa petite taille et connu pour ses aventures et ses entreprises dangereuses. Cet homme se leva et dit :

— Soundiata a mal agi, car Fakoly-Koumba est un homme qui ne tient pas sa langue. Il dit tout ce qu'il voit et répète tout ce qu'il apprend, et nul ne doit lui donner une femme.

Soundiata le fit mourir, puis partit avec son griot pour faire le tour de son royaume.

En chemin, le griot eut faim, mais ils chassèrent en vain. Alors Soundiata dit à son griot de l'attendre. Il alla vers un arbre situé à quelque distance de là et s'étant caché, il coupa une bonne tranche dans sa cuisse. Et comme le sang coulait abondamment, il enveloppa la plaie de feuilles d'arbre. Puis il porta sa propre chair au griot, qui lui demanda :

— Quelle viande est-ce là ?

— J'ai tué un éléphant, répondit Soundiata, et comme il était trop gros pour que je puisse l'apporter en entier, j'ai coupé ce morceau pour toi.

Ils cherchèrent ensemble du bois mort ét le griot rôtit la viande qu'il trouva bonne et savoureuse. Soundiata l'interrogea :

— Est-elle bonne, mon griot ?

— Depuis ma naissance, répondit le griot, je n'ai goûté une viande aussi douce.

Soundiata venait de commettre l'acte de dissimulation le plus illustre et le plus sacré de l'histoire, celui qui rend la vie aux morts, qui parfume les chairs immondes et ranime les défaillants. Et voilà que tout à coup il méditait sur son mensonge. Il se disait: « J'ai commis un acte indigne d'un héros, mais je l'ai fait pour sauver un homme de la faim. Désormais, le mensonge bienfaisant sera protégé. » Mais Soundiata, à la longue, regretta d'avoir menti à son griot et ordonné que le mensonge bienfaisant fût protégé. Car le mensonge bienfaisant menaçait de désorganiser son royaume en apportant au sein du peuple de nouvelles croyances, de nouvelles convictions, une foi nouvelle.

Et en effet, quelque temps après, les hommes s'en allaient, soufflant dans l'oreille du voisin :

— Il y a en haut un souverain inégalable et une justice suprême qui réparera nos malheurs.

Et ces hommes-là disaient encore :

— Notre maître Soundiata-Keita n'est pas unique dans l'univers.

D'autres s'en allaient proclamant que la chair des animaux pouvait être mangée, que les animaux étaient un tribut donné à l'homme par la nature. D'autres enfin, s'en allaient, disant que ceux qui régnaient sur la terre ne régneraient pas dans les cieux.

Mais Soundiata ne regretta pas de s'être taillé la cuisse pour faire manger son griot. Le griot représente l'honneur, et l'honneur passe avant la santé, avant le ventre. Qui que tu sois, agis comme Soundiata-Keita, le souverain puissant entre tous. Ne laisse pas mourir ton honneur, c'est ta vie.

Le griot manifesta sa soif, alors Soundiata frappa la terre de son pied, et l'eau d'une rivière voisine, qu'on ne voyait pas, coula à leurs pieds. Le griot dit :

— Ah ! seigneur, tu as creusé un grand puits !

Et il se mit à énumérer tous les aïeux de Soundiata, depuis Narman-Diata et même avant lui. Mais il y avait un crocodile dans le puits. Tout le Manding et les troupeaux du Manding boiraient désormais à ce puits.

Soundiata, revenu chez lui, y trouva un homme qu'il interrogea en disant :

— Qui es-tu ?

— Vala-Birahima, répondit l'autre, l'ancêtre des cordonniers. Il me revient que tu as convoqué tous les chefs des tribus, sauf moi ?

— Si je ne t'ai pas fait venir, dit Soundiata, c'est que tu n'es pas capable de garder un secret.

Soundiata avait un bonnet qu'il n'enlevait jamais. Etant né avec ce bonnet, il le conservait en dormant, au sein des assemblées, ainsi que dans la mêlée et nul n'osait y faire allusion. Il dit à Vala-Birahima :

— Attends-moi là.

Il entra dans sa case, en sortit et montra au cordonnier sa tête qui était partagée en deux moitiés, l'une étant d'or et l'autre d'argent. Et comme Vala retenait son coeur de peur que le choc de l'émotion ne le fît sauter, Soundiata lui commanda de garder le secret. Vala-Birahima, l'ancêtre des cordonniers, retourna chez lui, mais son besoin de parler fut tel qu'il en éprouva un violent mal au ventre. Or, sa femme l'interrogea :

— Mais qu'as-tu donc ?

Et il disait :

Oung oung ! comme un chien malade.

Puis il alla creuser un trou dans la terre pour y enfouir le secret. Il dit :

— J'ai vu la tête de Soundiata, l'un des côtés est d'or, l'autre d'argent.

Et du coup son mal fut conjuré*.

Soundiata alla trouver son frère consanguin, Soumangourou, dans son pays. Pour interdire l'accès de sa capitale à Soundiata, Soumangourou y fit mettre le feu. Et Soundiata rebâtit la ville neuf fois sur dix; Soumangourou détruisit la ville et neuf fois sur dix, Soundiata la reconstruisit. La dixième fois, Soundiata, excédé par le caprice de son frère consanguin, le poursuivit avec la ferme volonté de le tuer. Mais au moment où il allait le frapper de sa lance, Soumangourou se changea en statue avec son cheval. Soundiata lui parla :

— Aké té ri ?**

Or Soumangourou répondit, bien qu'il ne fût plus à ce moment-là qu'un amas de boue inerte:entre

— Je suis toujours un homme.

Cette statue existe toujours dans le Manding et répond toujours à ce qu'on lui demande, mais il faut être un descendant de Soundiata-Keita pour avoir le privilège de la voir et de s'entretenir avec elle. Aux yeux des autres mortels, elle passe pour un tertre sans intérêt fait par la nature pour servir de royaume au peuple des fourmis et des termites.

Puis Soundiata dit :

— Il y a trop d'hommes dans le Manding. Aujourd'hui j'en ferai de la pâture pour les vautours.

Il fit venir Noumou-Fayourou, l'ancêtre des forgerons, des bijoutiers, des fondeurs et de tous ceux qui façonnent les métaux. Il lui ordonna de prendre dans le pays tous les hommes de petite taille et de les amener. Cela fut fait et Soundiata les tua et les offrit aux vautours, derrière le village. « Ha ! les vautours ont faim », disait-il. Il leur offrit aussi des boeufs parmi les plus gros du royaume.

Les vautours sont d'anciens rois déchus. Ils ne peuvent plus avoir de l'homme que la charogne et ne viennent que quand on les invite. De leur règne de jadis, ils n'ont gardé que la majesté.

Son principal esclave, Makan-Soundiata, ayant appris cela en fit autant. Et Soundiata, mis au courant, entra dans une grande colère. Il dit :

— Akona dioug, ako ne bra fa han lé Soun Diata, bé kou nè diong afana béoulé nkéla. Ave! (Mon esclave a maintenant le ventre plein. Il veut maintenant faire comme moi. Mais je vais lui faire voir ce qu'il est. Je vais le circoncire une seconde fois, le raser et lui mettre le bonnet puéril de ceux qui n'ont qu'une seule pensée).

Il fit tout cela puis tua l'esclave.

Si Soundiata a fait choisir les hommes de petite taille pour les offrir en pâture aux vautours, c'est que dans tous les pays, depuis les événements de Ouagadou, ils se distinguent par leur amour des aventures et des entreprises dangereuses. Ils désorganisent les Etats, commettent l'adultère et entreprennent souvent des choses qui sont audessus de leur pouvoir et de leurs forces. Ou bien, à l'exemple de cet autre bien connu, ils se mêlent de contrecarrer les décisions des souverains, se lèvent au milieu d'une assemblée pour dire au souverain: « Tu as mal agi. »

Un jour, Soundiata trouva chez lui un grand marabout qui faisait tous les matins ses prières. Mais Soundiata le voyait se lever de très bon matin, pour se livrer à des exercices vagues et inquiétants. Alors il se dit: « Je vais tuer cet homme, car c'est un traître; il n'y a que les traîtres qui se lèvent de si bon matin. » Et il tua le marabout.

Soundiata déjeunait d'un taureau, mais il ne mangeait pas le soir. Et du taureau il ne restait que les os et les poils. Quand il avait bu dans un canari, il fallait le remplir de nouveau, car il prenait en une seule fois tout le contenu du canari.

Soundiata convoqua tout le Manding et dit à tous :

— Sachez que le monde ne doit pas connaître un seul roi. Après moi, d'autres viendront et ceux-là vous feront voir des gouvernements bons ou mauvais, meilleurs ou pires que le mien. Car c'est moi qui ai fait tomber le baobab séculaire de Tam-Diara-Fodé que nul de mes aïeux n'avait pu faire tomber. J'étais venu parmi vous pour remplacer Narman-Diata-Konaté afin de régner sur la terre. Tiramakan est mon tuteur, et je suis venu de Sankaran dans le ventre de ma mère.

Un vieillard venu d'Aoudi, nommé Moulai-Traoré, lui demanda une faveur en disant :

— Je veux que tu m'accordes un coin de terre où je pourrai faire mes prières.

Soundiata accorda ce qu'il demandait. Or les enfants allèrent le regarder faire le salam et s'en vinrent raconter la chose à Soundiata. Ils disaient :

— Celui à qui tu as donné le coin de terre passe son temps à se lever et à se baisser.

Soundiata, ayant fait venir Moulai-Traoré, l'interrogea :

— On dit que tu passes ton temps à te lever et à te baisser. As-tu des regrets ?

Or le griot de Soundiata était à côté de lui et disait ses louanges. Et Soundiata fit baisser le marabout durant un jour entier et le tua le lendemain.

Les hommes d'Aoudi, apprenant cela, décidèrent d'attaquer Soundiata. Car Aoudi était le pays de MoulaiTraoré, le marabout qui passait son temps à se lever et à se baisser.

La bataille eut lieu et fut funeste pour ceux d'Aoudi. Lorsqu'ils aperçurent au loin Soundiata qui approchait, ils dirent tous : « Voyez cette montagne qui s'avance ».

Soundiata n'eut presque pas besoin de se battre sérieusement avec eux. Il lui suffisait de crier ou de braquer violemment son regard sur eux, chacun de ses cris faisait mourir vingt guerriers d'Aoudi ; chacun de ses regards de feu tuait vingt guerriers d'Aoudi. Après cela, il alla dans le Boundou qu'il mit à feu et à sang, et revint au Manding.

— Je suis venu, disait-il, dans Souma-Woro. L'homme connaît les yeux de l'homme.

Une fois de plus, il convoqua tout le Manding et dit :

— Un chien qui voit un savon et s'en empare, ne laissera pas un os.

Soundiata, le plus souvent, parlait à son peuple en employant des paraboles. Dans ces moments-là, il était grand parmi les grands et sage parmi les sages. Mais les anciens comprenaient parfaitement le sens de ses paraboles. Soundiata ajouta :

— Je n'ai qu'un seul regret, c'est que je dois laisser les guitares au monde et que mes petits-fils n'accompliront pas les mêmes exploits que moi en entendant la voix des coras. Je veux donc faire disparaître tous ces instruments de la terre.

Mais son griot se leva et dit :

— Il est vrai que tu as pris la cora d'entre les mains du djinné, et que la cora est le premier instrument connu du Manding. Mais je t'accompagnais lorsque tu vainquis le diable dans la rivière; j'ai donc ma part dans l'existence des coras et tu ne saurais les détruire entièrement.

Et Je griot ajouta : « Tu ne dois pas les détruire à cause de mes petits-fils à moi, qui n'auraient rien pour vivre. »

Et Soundiata dut laisser au monde les coras, les balafons, les guitares et les violons pour l'usage des petits-fils de son griot.

Paix à ta mémoire, Soundiata-Keita, souverain puissant entre tous. Tes petits-fils sont vaillants, mais le monde a changé. Le son des coras et des guitares ne leur inspire plus cette fougue belliqueuse qui armait ta main quand tu allais soumettre le Boundou et le Bélédougou. Mais d'autres choses comblent leurs mains qu'ils distribuent généreusement lorsqu'on évoque ton souvenir. Car n'avais-tu pas, caché derrière un arbre, coupé un bon morceau dans la chair de ta cuisse pour faire manger ton griot? Et n'as-tu pas dit et ordonné que le mensonge bienfaisant fût protégé? Aussi bien, tes petits-fils, fidèles à ta mémoire, conservent-ils une âme encline aux grandeurs de toutes sortes qui emplirent ton règne.

Soundiata, ayant fait venir tout le Manding, lui dit de nouveau :

— Mon heure approche, demain je m'en retournerai chez moi.

Et cette fois-là, les anciens eux-mêmes ne comprirent pas le sens de ses paroles. Alors Soundiata s'expliqua plus clairement, et jusqu'aux plus petits tout le monde comprit que le souverain puissant allait quitter le monde. Or, Tam-Diara-Fodé se leva et dit :

Quand tu auras quitté le Manding, mon baobab renaîtra. Car le présent est grand et peut nous donner des lois, mais le passé doit toujours manger le présent. Tout présent doit un jour devenir passé. Seul le passé est grand et éternel.

Soundiata l'écouta parler et lorsque Tam-Diara-Fodé eut fini, il ajouta simplement:me..

— J'ai régné sur la terre, demain je m'en retournerai chez moi.

Le lendemain, tout ce qu'il y avait de musique dans le Manding fut en branle: taboulas de deuil et d'allégresse, coras, guitares, violons et monocordes... Le peuple s'assembla pour assister à la fin de son souverain.

Soundiata alla se mettre loin de tous et contempla son peuple durant des heures entières. Puis il disparut tout à coup aux yeux de tous. Et tout le Manding, figé sur place, ne put s'en aller qu'au moment où la nuit vint couvrir la terre.

Ainsi finit l'histoire de Soundiata-Keita, le souverain puissant entre tous.

Tiramakan, l'ancêtre des chasseurs, devint empereur du Manding.

* Conjurer: exorciser, chasser les démons.

** N'es-tu pas un homme?

Knight, Roderic. 1992. "Kora Music of the Mandinka: Source Material for World Musics." In African Musicology: Current Trends, ed. Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje, 2:81-97. Los Angeles: African Studies Center, University of California.

(Sunjata)

p. 82

The Mali national anthem is also based on a tradtional Mande song, Sunjata mang bori long (Sunjata knows not running).

Example 1. The Mali national anthem (melody only), transcribed from the television broadcast sign-off. The original tune of Sunjata mang bori long, relatively unchanged begins on the third line. The original words are indicated. Translation: "Sunjata knows not running; Death is better than shame."

Kouyate, (El Hadj) Djeli Sory. 1992. Guinée: Anthologie du balafon mandingue. Vol 1. Buda, 92520-2.

(Soundjata)

[Soundjata] is dedicated to the great prince of the Mandingo, Soundjata Keita.

Kaba, Mamadi. 1995. Anthologie de chants mandingues (Côte d'Ivoire, Guinée, Mali). Paris: Harmattan.

(Soundiata)

pp. 66-7

C'est à Simbo que je m'adresse !

C'est à Diata que je m'adresse !

Diata, sorcier chasseur,

Diata, le grand seigneur !

Accourez !

Accourez !

Venez, hommes vaillants !

Soundiata a marché !

Accourez !

Accourez !

Venez femmes vaillantes,

Soundiata a marché.

Djata, le fils de Sogolon,

Djata, le lion du Manding

Vient de marche.

Il a pris le carquois.

Djata, fils de Sogolon

A pris le carquois

Pour aller à l'aventure

Pour aller à l'attaque

Gnama ! Gnama ! Gnama !